增進城市地區生物多樣性—以新加坡模式為例

著:(新加坡)林良任 (新加坡)陳莉娜 (新加坡)魯·艾德里安·福銘 譯:邢子博 校:張天潔 (新加坡)李天嬌

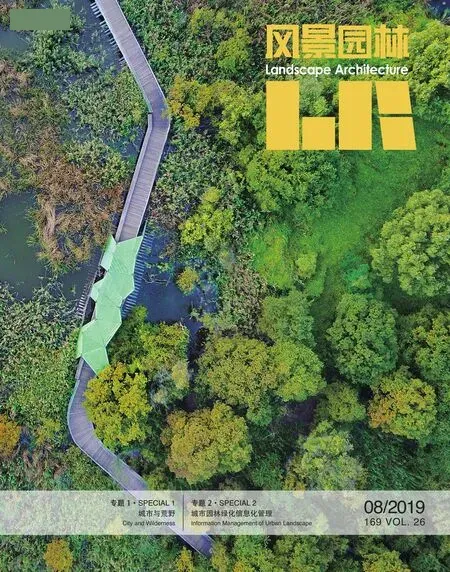

近年來,新加坡已被公認為第一世界國家中成功的“花園城市”,這里的城市基礎設施被納入綠化網絡結構之中。在政治意愿和遠見的結合推動下,通過專業和有素養的技術機構支持,新加坡半個世紀以來一直致力于綠色城市景觀的實踐(圖1)。

在過去十年中,關于城市及其人口如何與周圍和內部的自然生態系統相互作用,并從中獲益這一話題,人們的關注點在發生轉變。城市規劃師們開始致力于推廣“自然城市化”和“自然設計”,以此來闡釋在城市景觀設計中,如何將綠化和生物多樣性融入基礎設施。新加坡一直在引領這一新興趨勢,處在城市綠化戰略的前沿。這不僅包括簡單的舒適性種植設計,還制定以科學為基礎的戰略來保護自然生態系統,并在高度城市化的島嶼國家中和諧地支持生物多樣性。

1 背景

當史丹福·萊佛士爵士(Sir Stamford Raffles)于1819年登陸新加坡時,這里的大部分地區都被原始的低地龍腦香林、淡水沼澤、紅樹林等覆蓋。

不同于普遍的認知,新加坡原始森林消失的原因并非現代城市的發展,而是19世紀農業的出現。由于農業的快速發展和聚集,到1930年,新加坡超過90%的天然林已經被清除[1]。1965年新加坡獨立時,繼承了一個幾乎沒有原始森林覆蓋的島嶼,只剩下自然生態系統的若干碎片。自獨立以來50年的時間里,新加坡是如何在極高人口密度下,從一個景觀貧瘠的地區轉變為獲評MIT Senseable City Lab's Treepedia綠色景觀指數高的城市之一的?

2 現代新加坡—由“花園城市”轉變為“花園中的親生態城市”

“我們在建設,我們在進步,但是沒有什么比建成東南亞最干凈和綠化的城市更具特色和意義的成功標志了。”

摘自李光耀先生于1968年10月1日在首次舉辦的新加坡清潔運動中的演講

1963年6月16日,新加坡植樹活動中,當時在任總理李光耀先生種植了一棵黃牛木(Cratoxylum formosum)。這一歷史性事件標志著新加坡向著花園城市綠化之旅邁出了第一步。在最高政治層面,有一個強烈的愿景和清晰明確的指示,即新加坡應該是一個干凈的“綠色花園城市”,并成為當時第三世界死水中的綠洲。李光耀先生認為,綠化和清潔不僅是新加坡高效和良好治理的顯著表現,還應該讓社會各階層都能獲得利益,而不僅是富人階層。為了讓新加坡綠化程度達到更高水平,國家公園局提出將新加坡打造成花園城市的愿景。

21世紀,新加坡的綠化和自然保護,以科學方法為基礎,了解綠色植物和生物多樣性并從中受益。新加坡認為多樣的生態系統和棲息地及所有物種是其豐富而古老的自然遺產不可分割的一部分。新加坡也從最近的研究中得到啟示,這些研究表明綠色和生物多樣性城市具有很多優勢—例如干旱和洪水等極端天氣事件的恢復和緩解;空氣污染物的減少;公民身心健康的改善—為一個有彈性、可持續和宜居的國家做出貢獻。

基于此,新加坡在第一世界經濟中建立了一個令人印象深刻的綠色矩陣—一個“花園中的親生態城市”。新加坡是一個島嶼上的城市國家,陸地面積約719 km2。盡管保持著高度的城市化,新加坡仍然擁有豐富的原生物種,包括約2 215種植物(記錄在冊的)、61種哺乳動物、403種鳥類、334種蝴蝶、131種蜻蜓、800多種蜘蛛[2]583-609。海洋生物多樣性同樣豐富,包括12種海草、255種硬珊瑚和200多種海綿(表1)[3]。更令人驚訝的是,新加坡不斷發現過去未曾被記載的新物種,或重新發現被認為已經滅絕的物種。過去五年所記錄的480多種動植物就證明了這一點[4]。

1 新加坡武吉知馬自然保護區鳥瞰Aerial view of Singapore from above Bukit Timah Nature Reserve

2 新加坡自然保護區Nature reserves in Singapore2-1 武吉知馬自然保護區Bukit Timah Nature Reserve2-2 中央集水區自然保護區Central Catchment Nature Reserve2-3 雙溪布洛濕地保護區Sungei Buloh Wetland Reserve2-4 拉布拉多自然保護區Labrador Nature Reserve

未來的目標不僅是在土地受限、建筑密集的景觀中,確保新加坡豐富的本土生物多樣性持續發展,而是創造一個“城市生態系統”。在這里,基礎設施和人類活動與生態系統服務和綠化提供的益處相互協同。生物多樣性的解決方案必須以多學科、跨部門和綜合方法為基礎,所有利益相關方全面參與,并得到強有力的科學研究支持。

3 自然保護藍圖

以基于科學原則為指導,新加坡自然保護藍圖(The Nature Conservation Masterplan,簡稱NCMP)致力于集合、協調、鞏固和增強新加坡生物多樣性保護工作[5]。通過加強生態聯系來建立生態彈性,這將有助于保護本土生物的多樣性和適應氣候變化帶來的影響。

NCMP包括4個重點:1)核心棲息地保護;2)棲息地強化和恢復,物種復育;3)在保護生物學和規劃方面進行穩健可靠的研究;4)社區管理和外展活動。以上所有的保護舉措都包括海洋、沿海、陸地生態系統,覆蓋生態系統、物種和基因各層面。

3.1 保護核心棲息地

核心棲息地保護主要目標是保護和加強核心生物多樣性區域,保護和增強緩沖區,在新加坡加強和管理其他綠化節點,發展生態聯系,并將自然與更廣闊的城市景觀融為一體。

核心生物多樣性地區包括:1)武吉知馬自然保護區(圖2-1);2)中央集水區自然保護區(圖2-2);3)雙溪布洛濕地保護區(圖2-3);4)拉布拉多自然保護區(圖2-4);5)包括烏敏島和姐妹島海洋公園在內的自然區域,這些地區擁有新加坡大部分的原生物種,是關鍵的基因存儲庫和來源。多樣化的生態系統都體現于這些核心地區,包括低地龍腦香林、次生林,淡水沼澤、溪水和河流、草原、紅樹林、巖石海岸、沙質海岸、潮間帶泥灘、海草草甸、珊瑚礁、開闊水域等。新加坡的用地非常集約緊湊,這些地區距離樟宜國際機場都只有40 min的車程。沒有天然腹地的新加坡是世界上少數幾個核心自然保護區位于城市內的國家。

為了緩解這些重要核心區域的邊緣效應,如防止干燥條件、強風和外來入侵物種的滲透,核心區域附近被指定為自然公園。例如,中央集水區自然保護區周圍有策士納自然公園、正華自然公園、春葉自然公園、湯申自然公園、溫莎自然公園、牛乳場自然公園、海希德自然公園、射靶場自然公園等(圖3)。同樣,雙溪布洛濕地保護區的擴建包括克蘭芝沼澤、萬禮紅樹林和灘涂,這有助于有效保護生物多樣性所需的臨界標準。

在核心區域之外也發現了許多珍稀瀕危物種。為了更全面地保護這些物種,對其他綠化節點生物多樣完整性的增強工作同樣受到特別關注。

為了對抗自然棲息地的碎片化,上面提到的緩沖公園以及生態連接網絡,都是作用于擴大本土動植物生態空間的關鍵因素。緩沖公園增加了核心自然保護區的生態足跡,生態連接提供了一個島嶼范圍的基質,以提供原生動物覓食和繁殖所需的空間,并使原生植物得以分散。正是基于這一原則,通過利用地理信息系統(GIS)建模技術追蹤阻力最小路徑等方法,確定了核心區域的潛在生態連接。橫跨313 km的公園連道,80 km的自然連道[6]—Eco-Link @ BKE(圖4),以及多層種植道路與本土植物物種(圖5),這是為擴大新加坡生態連通性而實施的一些舉措。此外,立體綠化項目是鳥類、蝴蝶、蜻蜓和其他飛行動物的墊腳石。

3 中央集水區自然保護區周圍的自然公園Nature parks surrounding the Central Catchment Nature Reserve

4 Eco-link @ BKE是一條架空生態走廊,旨在恢復兩個自然保護區之間的生態連接The Eco-link@BKE,an overhead ecological corridor constructed to restore ecological connectivity between two Nature Reserves

5 多層種植創造了多種生態位,已應用于路邊綠化Multi-layered planting that creates multi ecological niches has been applied to roadside greenery

為了增加對豐富的海洋生物多樣性的關注,制定了海洋保護總藍圖(MCAP)。MCAP強調的其中一項舉措是建立姐妹島海洋生態園(SIMP,圖6),該公園位于世界上最繁忙的港口之一的常規航道中間。多主體建模研究結果支持SIMP的選址,因為它是海洋生物的潛在有效源礁。海洋生物的卵或幼蟲可以分布在新加坡的所有沿海和海洋區域。SIMP的目標是促進保護、研究、教育和外展。目前SIMP正在建立一個原位硬珊瑚儲存庫,目的是保存新加坡發現的所有本地現存硬珊瑚物種,其數量可達全球800多種硬珊瑚物種的30%以上。

國家公園局還制定了綜合城市沿海管理(IUCM)計劃,以促進沿海地區的協調活動[7]。這種模式已在諸如東亞海洋環境管理伙伴關系(PEMSEA)等區域論壇上分享。隨著更多沿海城市的城市化推進,這一模式將愈加凸顯其價值。

3.2 加強和恢復棲息地并協助物種恢復

多年來,由于人類的活動和土地利用的變化,城市的自然景觀不可避免會出現退化。隨著越來越多的證據表明:生物多樣性提供了有益人類健康和福祉的生態系統,有必要通過棲息地恢復、增強和創造來修復自然區域的功能完整性。因此,NCMP的第2個重點是核心區域,緩沖區、其他綠化節點和生態連接的棲息地增強及恢復以及物種復育。

除了在自然區域實施之外,棲息地增強技術也適用于城市景觀單一或生物多樣性貧乏地區。烏節路是新加坡最繁忙的購物區之一,與之相交的一條小路布滿了吸引蝴蝶的植物。在新加坡植物園學習森林(圖7)中修復了一個被稱為吉寶探索濕地的淡水濕地棲息地,該森林位于新加坡植物園的緩沖區,是一個聯合國教科文組織世界遺產。它是受威脅的淡水動植物的避難所,使水文過程得以恢復,低地雨林得以再生,人們得以更接近自然[8]。

2019年1月,國家公園局公布了森林修復計劃,該計劃旨在通過恢復生態過程和加強生物多樣性、生態連通性來增強原生雨林的復原力。該行動計劃還希望協助早期次生林繼續成長為更成熟和多樣化的雨林,從而改善生物多樣性的棲息地。方法包括:種植可以固定氮的原生植物,以自然地改善土壤條件并且吸引傳粉者和傳播動物,清除雜草以協助再生、引入主要的雨林物種等。

在像新加坡這樣物種豐富的小島上,大部分動植物種群都將不可避免地面臨滅絕的威脅,特別是當地特有物種。這些物種已經得到了額外的援助,以確保其數量能夠達到可持續的水平。例如,世界上最大的蘭花—老虎蘭(Grammatophyllum speciosum,圖8),曾被認為在新加坡已經滅絕。隨著在苗圃的繁殖和全島的廣泛種植,老虎蘭在新加坡的保護狀況得到了極大的改善。當這些蘭花在公園、花園和道路上盛開時,它們總會使人心情愉悅。同樣,新加坡蕊木(Kopsia singapurensis)是僅在馬來西亞半島和新加坡的淡水沼澤森林棲息地中生長的物種,并且在當地處于極度瀕危狀態。該物種的遷地保護項目已經到位,在新加坡植物園和巴西班讓苗圃進行扦插,并在森林改良和恢復項目中種植,例如鐵路走廊的重建項目。

東方斑犀鳥(Anthracoceros albirostris,圖9)曾經一度被認為在新加坡已經滅絕。1997年,一些犀鳥飛到烏敏島(Pulau Ubin)筑巢。研究表明,限制該鳥類繁衍的因素是適合筑巢地點的缺乏。在幾個不同位置的高大樹木中設立智能巢箱,隨之該種犀鳥數量現已增加到100多只。

另一個在新加坡重現的魅力物種是滑毛江獺(Lutrogale perspicillata,圖10)。在新加坡,它曾經被認為已經滅絕,20世紀90年代中期才重新出現。沿海棲息地以及市政水道(如碧山—宏茂橋公園和濱海灣)的強化促進了該物種的重現。如今,滑毛江獺的數量超過70只。包括國家公園局的新加坡水獺工作小組與民間水獺保育組織同心協力,以多學科、利益相關者相互配合的方式監測追蹤水獺的數量及動向,保護該物種。

目前的物種復育計劃包含了新加坡特有的新加坡淡水蟹(圖11)。這種溪蟹被國際自然保護聯盟列為全世界前100種受威脅的物種之一。國家公園局正致力于人工繁殖,轉移部分群種至適當的溪流及研究該物種的生態需求。至今,已經有超過300只小螃蟹在人工繁殖技術下成功孵化。

值得注意的是標志性的杯狀大海綿(Cliona patera)在新加坡的重新發現。該物種曾一度被認為已經滅絕了近一個世紀。直到1990年,一個個體在澳大利亞海岸被打撈上來。2011年新發現了2個活體樣本,隨后又發現了3個樣本,使新加坡成為目前世界上唯一擁有該野生海綿已知樣本的地方。5個以上的杯狀大海綿被轉移到姐妹島海洋生態園附近的最佳生存地點,它們的生長和健康狀況被持續監測。

6 姐妹島海洋生態園The Sisters' Islands Marine Park

7 新加坡植物園學習森林修復的淡水濕地棲息地The restored freshwater wetland habitat at the SBG Learning Forest

8 老虎蘭,世界上最大的蘭花The Tiger Orchid,largest orchid in the world

3.3 保護生物學與規劃的應用研究

第3個重點包括各種舉措,例如,綜合調查[2]3-17,[9-11]以及對生態系統和物種的長期監測,定量生態研究,基于科學的政策制定和管理規劃。國家公園局研究和運營工作的一個關鍵優勢是不斷應用最新技術,包括地理信息系統、多主體建模、數值建模、基因組學、3D建模和激光雷達等。新加坡生物多樣性的保護和研究是在不同層面上進行的:整個國家層面、景觀層面、地表層面甚至下至微觀和基因層面。

在整個國家層面,衛星圖像是國家公園局開展各種研究項目的一個非常強大的工具。從確定新加坡綠色覆蓋的真實性,到為連通性研究辨識綠色走廊,甚至是做衛星圖像的光譜分析以檢測不健康的森林斑塊,國家公園局利用這項技術作為規劃和決策支持工具(圖12)。

在景觀層面,另一套高科技工具也被應用于規劃、保護和樹木栽培等多個領域。整個街景的激光雷達模型用于估算樹冠的生長速率和確定適當的修剪措施。研究沿海動植物(包括濱鳥、珊瑚幼蟲和紅樹林繁殖體)運動的多主體模型可以保護作為覓食地或增長來源的重要棲息地。無人機技術也已成為綠化研究和運營的重要技術工具。空中無人機是一種低成本的解決方案,可以幫助追蹤棲息地以及再造林隨著時間推移的增長狀況,調查蘭花和其他附生植物的樹冠,甚至調查樹木的缺陷。

在地表層面,生物多樣性調查仍然是保護研究的關鍵組成部分。近期陸地和海洋生態系統調查顯示,已發現至少3個新的當地獨有植物物種,即Zingiber singapurense(姜屬的一種)、Hanguana rubinea(匍莖草屬的一種)、Hanguana triangulata(匍莖草屬的一種)、150余種長腿蒼蠅和超過100種未發現過的海洋生物。盡管新加坡是世界上最繁忙的港口之一,通過確保在海洋航道之外有足夠的海洋棲息地,并且在海洋環境中開展發展項目時積極采取緩解措施,新加坡海洋生物多樣性的豐富性得到了保障。新物種的持續發現表明新加坡尚未達到新物種發現曲線的穩定期。同樣令人鼓舞的是,許多以前被認為已滅絕的植物物種,即50年來都沒有記錄的物種,已經通過系統性和強化后的實地調查被重新發現(圖13)。

技術進步也改變了生物多樣性調查的格局。尤其是紅外相機和夜視鏡的使用大大推動了森林脊椎動物的夜間研究,因為這些動物大多數只在夜間活動(圖14)。其他調查方法的創新包括在陸地或海洋環境中使用聲學傳感器監測動物的發聲,或與聲吶裝置結合,確定沿海和海洋物種的種類和個體數量,譬如海豚、鯨魚甚至鱷魚。

在詳細了解新加坡的物種知識后,展開了對物種之間錯綜復雜的相互關系定量研究和生態研究的課題。利用最新的預測建模工具對這些復雜聯系的結果進行分析,設計出更好的管理計劃,并促進基于科學的決策。

在分子和遺傳層面,DNA分析作為一種先進的調查方法,正在成為進一步研究新加坡和區域內其他地區動植物物種之間關系的手段。為了更好地了解物種的遺傳可行性,對新加坡萊佛士葉猴的種群進行了遺傳研究。環境DNA或環境“eDNA”研究目前正在進行,目的是部署該技術以監測新加坡水域的各種海洋生物,包括可能的外來入侵物種(圖15)。

3.4 社區管理與自然界的拓展

NCMP的最后一個目標是通過自然社區(CIN)計劃增進整個社區的生態包容性。CIN是2011年9月啟動的一項全國性運動,旨在聯系和促使社區中的不同群體成為新加坡自然遺產的共同擁有者,包括家庭、獨立人士、教育和研究機構、大小型公司、非政府組織以及政府機構。

CIN的一些舉措包括:1)將生物多樣性納入教育系統的各個層面;2)制定強有力的公民科學計劃,使公眾、學校、科學家和業余自然學者參與到年度“生物多樣性速查”,觀察鳥類、蝴蝶、蒼鷺和蜻蜓活動(圖16);3)學校組織綠化活動,以增進生物多樣性的實踐經驗,為學生提供實踐生物多樣性的調查,記錄生物多樣性和改善學校周圍棲息地的機會;4)維護新加坡生物多樣性的數據庫和分布地圖,公眾使用移動應用程序“SGBioAtlas”輕松地記錄生物多樣性;5)按順序組織一年一度的生物多元節(FOB),將有關新加坡自然遺產和生物多樣性的知識傳播到社區的中心地帶。

國家公園局于2019年5月18—26日舉辦活動,FOB將作為最后的壓軸。預計將有3 000名參與者參加全國范圍的“bioblitz”活動,覆蓋包括海洋公園在內的80多個地點。

此外,還有許多以社區為基礎的平臺可以讓公眾參與綠化和生物多樣性保護,包括錦簇社區、烏敏之友網(FUN)、烏敏島盛會和公園之友。這些不同的計劃和平臺共同運作,促使所有群體與新加坡人進行廣泛而深入的互動。國家公園局還鼓勵人們積極參與項目,甚至贊助企業的員工也作為實踐志愿者參與他們資助的項目。

4 監測的成果—新加坡城市生物多樣性指數

國家公園局是生物多樣性國家聯合公約(CBD)的國家聯絡點。為了記錄在綠化和生物多樣性保護方面的成功,并支持其他城市建立一套共同的成功指標,國家公園局與CBD秘書處合作,聯合“生物多樣性地方政府和城市的全球伙伴關系”,共同開發城市生物多樣性指數。以上也被稱為新加坡城市生物多樣性指數(SI),它是一種評估城市生物多樣性工作的自我評估工具[12]。全球有25個城市已經成功應用了SI,大約40個城市正處于應用SI的不同階段。

5 區域與國際承諾

國家公園局也是參加聯合國氣候變化框架公約會議的新加坡代表團成員。2015年7月4日,在德國波恩舉行的世界遺產委員會第39屆會議期間,新加坡植物園被列為新加坡首個世界遺產,這體現了對文化遺產的奉獻精神。為了表彰其對新加坡生物多樣性保護的重大貢獻,國家公園局榮獲2017年聯合國教科文組織蘇丹卡布斯環境保護獎。

由國家公園局管理的雙溪布洛濕地保護區和武吉知馬自然保護區已被認定為東盟遺產公園。

6 結論

綜合、長期的調查和監測表明,新加坡擁有豐富的本土生物多樣性。自然保護區和自然區域的維護,以及正確的公園管理(公園連接網絡)和街景管理的方式,為新加坡本土生物多樣性繁榮發展提供了合適的棲息地環境。此外,通過立體綠化和垂直綠墻將保護區拓展到空中,并將國家公園局的保護工作擴展到沿海和海洋環境區域,為自然城市的理解和實踐增加了多個維度的可能性。

這與兩個第三方的獨立評估一致。首先,Treepedia以綠色視圖索引(GVI)的形式測量城市中的冠層覆蓋。在他們分析的前27個城市中,作為人口密度最高的城市之一的新加坡高居第二,擁有29.3%的城市冠層覆蓋。其次,在Timothy Beatley 2016年出版的《自然城市規劃與設計手冊》一書中的第二部分,有一章專門撰寫了新加坡,主題是“創建自然城市:新興全球實踐”。

通過實施NCMP,國家公園局使生物多樣性保護融入城市發展歷程,從而將新加坡發展成一個宜居和可持續的親生態城市,一個人類和城市生物圈的模范城市②。

注釋:

① 公民科學家是指非學術或職業的科學家、科學愛好者和志愿者。這些公眾自動自發共同參與科研活動,收集數據并檢測生物多樣性的變化,致力于加強科學研究的普及化。

② 有關國家公園局生物多樣性保護工作的更多信息,請參閱:城市生物多樣性:https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7TlA-wSEwWQ;城市中的公園:https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jLRROkGGBfM;新加坡親生態城市:國家公園局關于生物多樣性保護工作的原始視頻:https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XMWOu9xIM_k。

圖表來源:

圖1~16?NParks;表1根據參考文獻[3]的605頁修改。

(編輯/劉玉霞)

Singapore has established a reputation over the years as a successful,first-world “City In A Garden”,where urban infrastructure is integrated into a matrix of greenery.Through a combination of political will and foresight,supported by dedicated and highlytrained technical agencies,Singapore has enjoyed a half-century of practical experience in realising a green cityscape (Fig.1).

In the past decade,there has been a shift in the focus of how cities and their human populations can interact with,and benefit from the natural ecosystems around and within them.City planners have become interested in promoting“biophilic urbanism” and “biophilic design” to illustrate how urban landscapes should integrate greenery and biodiversity into infrastructure.This emergent trend has been led by Singapore,which was in the forefront of evolving our urban greenery strategies to look beyond simple amenity planting,to science-based strategies to conserve natural ecosystems as well as harmoniously support biodiversity in a highly urbanised island city-state.

1 Background

When Sir Stamford Raffles landed in Singapore in 1819,most of Singapore was covered by pristine primary lowland dipterocarp forest,freshwater swamps,mangrove forests,etc.

Contrary to popular belief,the clearance of Singapore's original forests did not come with the advent of modern-day urban development,but rather,with 19th-century agriculture.Due to rapid and intensive agricultural development,more than 90% of the Singapore's natural forests had already been cleared by 1930[1].When Singapore gained independence in 1965,it inherited an island depleted of much of its original forest cover,and only fragments of natural ecosystems were left.How did Singapore in a span of 50 years of independence manage to convert an impoverished landscape to one that the MIT Senseable City Lab's Treepedia rated as one of the cities with the highest Green View Index in spite of its high population density?

9 東方斑犀鳥現在可以在新加坡的許多城市地區看到Anthracoceros albirostris can now be seen in many urban areas around Singapore

10 在主要水道和沿海棲息地中經常遇到滑毛江獺Lutrogale perspicillata is commonly encountered in major waterways and coastal habitats

11 新加坡特有極度瀕危的新加坡淡水蟹在人工繁殖技術下成功繁殖Johora singaporensis,a critically endangered endemic freshwater crab,with newly-hatched young in captivity

2 Modern Singapore—from Garden City to a Biophilic City in a Garden

“We have built,we have progressed.But there is no hallmark of success more distinctive and more meaningful than achieving our position as the cleanest and greenest city in South Asia”

Extract from Mr Lee Kuan Yew's speech at the launch of Singapore's first Keep Singapore Clean Campaign - 1 Oct.1968

Singapore launched its tree-planting campaign on 16 June 1963 when founding Prime Minister,the late Mr Lee Kuan Yew,planted a Mempat tree,Cratoxylum formosum.This historic event marked Singapore's first step in the green journey towards a Garden City.At the highest political level,there was a strong vision and clearly-articulated directive that Singapore should be a Clean and “Green Garden City”,and an oasis in what was then a Third-World backwater.Lee Kuan Yew believed that greenery and cleanliness not only served as a visible statement of Singapore's efficiency and good governance,but that greenery should be made accessible to all levels of the community rather than just the well-to-do.Taking the greening of Singapore to a higher level,NParks evolved its vision to making Singapore a City in a Garden.

Twenty-first century Singapore's approach to greening and nature conservation is founded on a science-based approach to understanding and benefiting from greenery and biodiversity.Singapore acknowledges the fact that its various ecosystems and habitats,and all its species are an inseparable part of the island's rich and ancient natural heritage.Singapore has also taken the cue from recent studies indicating that the benefits of a green and biodiverse city - such as resilience to and mitigation of extreme weather events like drought and flooding; reduction of airborne pollutants; and improvement in the physical and mental wellbeing of its citizenry- contribute to a resilient,sustainable and liveable nation.

With this in mind,Singapore has built an impressive green matrix in a first-world economy- a “Biophilic City In A Garden”.Singapore is an island city-state with a terrestrial area of around 719 square kilometres.Despite being highly urbanised,Singapore still harbours a wide range of native biodiversity,including around 2,215 plant species(ever recorded),61 mammal species,403 bird species,334 butterfly species,131 dragonfly species,more than 800 spider species[2]583-609.Its marine biodiversity,including,12 seagrass species,255 hard coral species,and more than 200 sponge species,is equally rich (Tab.1)[3].What is more surprising is that new species discovery and re-discovery of species previously thought to be extinct are still occurring,as evident from the over 480 new species of animals and plants recorded over the past five years[4].

The future goal is not just ensuring that Singapore's rich native biodiversity thrives in a land-constrained,densely built-up landscape,but to create an “urban ecosystem” where infrastructure and human activities are synergised with the ecosystem services and other benefits provided by greenery and biodiversity.The solution has to be based on a multidisciplinary,inter-sectoral and comprehensive approach,with an inclusive participation by all stakeholders,and supported by strong scientific research.

12 新加坡衛星地圖上繪制的生態網絡和連通性指數An ecological network and connectivity index plotted over a satellite map of Singapore

13 Marsdenia maingayi(左,牛奶菜屬的一種)和Renanthera elongata(右,火焰蘭屬的一種),最近都在中央集水區自然保護區重新發現Marsdenia maingayi (left) and Renanthera elongata (right),both recently rediscovered in the Central Catchment Nature Reserve

14 夜視設備,如紅外相機(左)和熱成像儀(右),對于研究許多夜間脊椎動物的種群和習性大有裨益Night vision equipments such as infrared camera (left) and thermal imaging equipment(right),have resulted in highly successful research into the population and ecology of many nocturnal vertebrate species

3 The Nature Conservation Masterplan

Guided by science-based principles,the Nature Conservation Masterplan (NCMP) consolidates,coordinates,strengthens and intensifies Singapore's biodiversity conservation efforts[5].These efforts will build ecological resilience through the strengthening of ecological linkages that will help us conserve our native biodiversity and also adapt to the effects of climate change.

The NCMP consists of four thrusts:firstly,the conservation of key habitats; secondly,habitat enhancement,restoration,and species recovery; thirdly,robust and credible research in conservation biology and planning; and fourthly,community stewardship and outreach in nature.All our conservation initiatives encompass terrestrial,coastal and marine ecosystems,at the ecosystem,species and genetic levels.

3.1 Conserving Our Key Habitats

The key objectives of the first thrust are to safeguard and strengthen the core biodiversity areas; secure and enhance buffer areas; enhance and manage additional nodes of greenery throughout Singapore; develop ecological connections; and integrate nature with the broader urban landscape.

The core biodiversity-rich areas comprising 1) Bukit Timah Nature Reserve (Fig.2-1),2) Central Catchment Nature Reserve (Fig.2-2),3) Sungei Buloh Wetland Reserve (Fig.2-3),4) Labrador Nature Reserve (Fig.2-4),and 5) Nature Areas including Pulau Ubin and Sisters' Islands Marine Park,harbour the majority of Singapore's native biodiversity and are the key gene pool repositories and sources.Diverse ecosystems,including lowland dipterocarp forests,secondary forests,freshwater swamps,streams and rivers,grasslands,mangroves,rocky shores,sandy shores,inter-tidal mudflats,sea grass meadows,coral reefs,open waters,etc.,are represented in these core areas.As an illustration of the compactness of Singapore,all these areas lie within a forty-minute drive from Changi International Airport.Without a natural hinterland,Singapore is one of the few nations on earth where its core nature reserves are located within the city.

To buffer these important core areas from edge effects like drying conditions,strong winds,and penetration by invasive alien species,areas adjacent to core areas are designated as nature parks.For example,the Central Catchment Nature Reserve is surrounded by Chestnut Nature Park,Zhenghua Nature Park,Springleaf Nature Park,Thomson Nature Park,Windsor Nature Park,Dairy Farm Nature Park,Hindhede Nature Park,Rifle Range Nature Park,etc.(Fig.3).Similarly,the extension of Sungei Buloh Wetland Reserve to include Kranji Marshes and the Mandai Mangrove and Mudflat contributes to the critical mass required for effective biodiversity conservation.

Many rare and critically endangered species have been found beyond the core areas.To more comprehensively conserve these species,special attention has been placed on enhancing the integrity of additional nodes of greenery.

To counter fragmentation of natural habitats,the buffer parks mentioned above,as well as a network of ecological connectors work together as key elements of a strategy to expand the ecological space available to native flora and fauna.Buffer parks add to the ecological footprint of core nature reserves and ecological connections provide an island-wide matrix for native fauna to forage and breed,and native flora to disperse to.It is based on this principle that we have identified potential ecological connections linking core areas using geographical information systems (GIS),modelling techniques to track pathways of least resistance,etc.Park connectors spanning 313 km,80 km of Nature Ways[6],the Eco-Link@BKE (Fig.4),and intensified multi-layering planting of roads with native plant species (Fig.5),are some of the initiatives implemented to extend ecological connectivity throughout Singapore.Additionally,skyrise greenery projects function as stepping-stones for birds,butterflies,dragonflies,and other flying animals.

To accord due attention to Singapore's rich marine biodiversity,we have prepared a Marine Conservation Action Plan (MCAP).One of the initiatives highlighted in the MCAP was the establishment of the Sisters' Islands Marine Park(SIMP,Fig.6) which is situated in the midst of the well-plied fairways of one of the busiest ports in the world.The results of agent-based modelling research support the location of the SIMP as it serves as a potentially effective source reef for marine organisms whose gametes or larvae can be distributed across all coastal and marine areas in Singapore.The objectives of SIMP are to promote conservation,research,and education and outreach.An in situ hard coral repository is currently being established at SIMP,targeting to harbour all native extant hard coral species found in Singapore,which amounts to over 30% of the global total of over 800 hard coral species.

NParks has also developed an Integrated Urban Coastal Management (IUCM) Programme that promotes coordinated activities in the coastal region[7].This model has been shared in regional fora such as the Partnership on Environmental Management in the Seas of East Asia (PEMSEA),etc.It will be increasingly relevant as more coastal cities expand their urbanisation.

3.2 Enhancing and Restoring Habitats and Assisting in Species Recovery

It is inevitable that natural landscapes in cities degrade over the years due to human activities and land use changes.With increasing evidence that biodiversity provides ecosystems that are beneficial to human health and well-being,it is essential that the functional integrity of natural sites be repaired through habitat restoration,enhancement and creation efforts.Hence,the second thrust of the NCMP focusses on a) habitat enhancement and restoration in core areas,buffers,other greenery nodes and ecological connections,and b) species recovery.

Habitat enhancement techniques,besides being implemented in natural areas,are also applied to urban landscapes or biodiversity-impoverished sites.A trail planted with butterfly-attracting plants spans a stretch of Orchard Road,which is one of the busiest shopping areas in Singapore.A freshwater wetland habitat,known as the Keppel Discoverl Wetlands,was restored in the SBG Learning Forest (Fig.7) which lies in the buffer zone of the Singapore Botanic Gardens,a UNESCO-inscribed World Heritage Site.It restores the hydrological process,regenerates the lowland rainforest,brings people closer to nature and serves as a refuge for threatened freshwater flora and fauna[8].

In January 2019,the National Parks Board unveiled the Forest Restoration Action Plan,which seeks to strengthen the resilience of our native rainforests by restoring ecological processes and enhancing biodiversity and ecological connectivity.The Action Plan also aims to assist the succession of early secondary forests to more mature and diverse rainforests over time,thereby improving habitats for biodiversity.The approach will comprise the planting of a framework of native plant species that fix nitrogen to naturally improve soil conditions and would also attract pollinators and dispersers.Removal of weed species will also be undertaken to assist regrowth.Dominant primary rainforest species will also be introduced.

In a small island like Singapore where species diversity is high,most of the populations of Singapore's flora and fauna,in particular,endemic species,will inevitably be endangered,threatened or rare.These species have been given extra assistance to ensure that their populations reach sustainable levels.For example,the largest orchid in the world is the Tiger Orchid,Grammatophyllum speciosum (Fig.8),once thought to be extinct in Singapore.With the propagation in nurseries and widespread planting of this orchid all over the island,the conservation status of the Tiger Orchid has greatly improved in Singapore.These orchids never fail to delight when they bloom in the parks,gardens and along the roads.Similarly,the Singapore Kopsia,Kopsia singapurensis,is a species found only in the wild in freshwater swamp forest habitats of Peninsula Malaysia and Singapore and is critically endangered locally.An ex-situ conservation project for the species is in place,with cuttings being cultivated in the Singapore Botanic Gardens and the Pasir Panjang Nursery and being planted out in forest enhancement and restoration projects,such as the rewilding of the Rail Corridor.

15 采集水樣用于各種水生或海洋生物的eDNA監測Samples of water are taken for eDNA monitoring for a wide range of aquatic or marine organisms

An avian species once thought to be extinct in Singapore is the Oriental Pied Hornbill,Anthracoceros albirostris (Fig.9).A few hornbills flew into Pulau Ubin to nest around 1997.Research indicated that the limiting factor was the lack of suitable nesting sites.With the erection of smart nest boxes in tall trees in several different locations,the hornbill population has now increased to more than 100 hornbills.

Another charismatic species that has made a comeback in Singapore is the smooth-coated otter,Lutrogale perspicillata (Fig.10).Once thought extinct in Singapore,the otter made a reappearance in the mid-1990s.The enhancement of coastal habitats as well as municipal waterways (such as the Bishan-Ang Mo Kio Park and Marina Bay) has resulted in the resurgence of the species.Today,the population of smooth-coated otters stand at more than 70 individuals.There is a collective,multidisciplinary approach towards otter conservation in Singapore,with the involvement of NParks and the Otter Working Group,which tracks the otter populations and movement islandwide.

Our current species recovery programmes include the endemic crab,Johora singaporensis,the endemic Cryptocoryne × timahensis,etc.To assist the long-term survival of the Johora singaporensis(Fig.11) which is listed by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources as one of the 100 most endangered species,NParks is carrying out ex situ breeding,translocating individuals to other suitable freshwater streams and researching on the ecological requirements of this endemic crab.To-date,more than 300 individuals of this crab has been successfully brooded in NParks' facility.

16 公民科學家①參與生物多樣性調查Citizen scientists① participate in biodiversity surveys

Of particular note is the rediscovery of the iconic Neptune's Cup sponge,Cliona patera,in its type locality of Singapore.It was once assumed extinct for close to a century until an individual was dredged up off the coast of Australia in 1990.The rediscovery of the first 2 live individual specimens in 2011 and the subsequent discovery of another 3 individuals make Singapore the only place in the world currently with known specimens of the sponge in the wild.More than five individual Neptune's Cup sponges have been translocated to optimum sites off the Sisters Island Marine Park,and their growth and health constantly monitored.

3.3 Applied Research in Conservation Biology and Planning

The third thrust comprises diverse initiatives such as a) comprehensive surveys[2]3-17,[9-11]and long-term monitoring of ecosystems and species;b) quantitative ecological research; and c) sciencebased policy formulation and management planning.A key strength of NParks research and operations work is the constant application of up-todate technology,including geographical information systems,agent-based modelling,numerical modelling,genomics,3D modelling,and LIDAR,amongst others.Conservation and biodiversity research in Singapore takes place at a hierarchy of levels - at the whole-ofcountry level; landscape level; ground level; and down to the microscopic and genetic level.

At the whole-of-country level,satellite imagery is a very powerful tool for a diverse range of research projects undertaken by NParks.From establishing the veracity of Singapore's total green cover,to identifying green corridors for connectivity research,and even to spectral analysis of satellite images to detect unhealthy patches of forest - NParks has leveraged on this technology as a planning and decision support tool (Fig.12).

At the landscape level,another suite of hightechnology tools is being applied in areas as diverse as planning,conservation,and arboriculture.LiDAR models of entire streetscapes allow for estimation of the growth rates of tree crowns and the determination of appropriate pruning measures.Agent-based modelling of the movements of coastal flora and fauna,including shorebirds,coral larvae and mangrove propagules,allow for the conservation of critical habitats that serve as either feeding sites or sources of recruitment.Drone technology has also become an important technological tool in greenery research and operations.Aerial drones provide low-cost solutions to help track the growth of habitat enhancement and reforestation sites over time; survey tree canopies for orchids and other epiphytic plants of interest; and even survey trees for defects.

At the ground level,biodiversity surveys remain a key component of conservation research.Recent surveys of both terrestrial and marine ecosystems have resulted in the discovery of at least 3 new endemic plant species,i.e.,Zingiber singapurense,Hanguana rubinea and Hanguana triangulata,more than 150 species of the Dolicopodidae longlegged flies,and over 100 new marine organisms.By ensuring that there are sufficient marine habitats outside of the maritime fairways and that mitigation measures are put in place when development projects are carried out in the marine environment,we have maintained marine biodiversity richness in Singapore despite being one of the world's busiest ports.The continued finding of new species indicates that we have yet to reach the plateau of the new species discovery curve.It is also heartening that many plant species that were previously thought to be extinct,i.e.,where sightings had not been recorded for over 50 years,have been re-discovered as a result of systematic and intensified field surveys(Fig.13).

Technological advances have also changed the game for biodiversity surveys.In particular,the use of camera traps and night vision equipment has allowed for highly successful nocturnal studies of forest vertebrates,of which a majority are active only at night (Fig.14).The next innovation in survey methodology involves the use of acoustic sensors,either on land or in the marine environment,to monitor either the vocalisations of faunal species,or in combination with sonar devices,determine the species and individual numbers of coastal and marine species such as dolphins,whales and even crocodiles.

Having obtained a good knowledge of the species found in Singapore,we are undertaking quantitative studies and ecological research on the intricate inter-relationships among species.The analyses of the results of these complex linkages with up-to-date predictive modelling tools will enable us design better management plans and facilitate science-based decision-making.

At the molecular and genetic level,DNA analysis is now coming to the fore as a means to further examine the relationships between flora and fauna species in Singapore and the rest of the region;as well as an advanced survey method.Genetic research has been conducted on the population of Raffles banded langurs in Singapore to better understand the genetic viability of the species.Environmental or “eDNA” studies are now being conducted with a view to deploying the technology to monitor Singapore's waters for a wide suite of marine organisms,including possible alien invasive species(Fig.15).

3.4 Community Stewardship and Outreach in Nature

The last prong of the NCMP seeks to involve the entire community for inclusiveness through the Community in Nature (CIN) programme.CIN is a national movement launched in September 2011 to connect and engage different groups in the community,including a) families,b) passionate individuals,c) educational and research institutions,d) corporations and companies,e) non-governmental organisations,and f) government agencies,to act as stewards of Singapore's natural heritage.

Some of CIN's initiatives include:a)incorporation of biodiversity into all levels of the education system,b) a strong Citizen Science programme where the public,schools,scientists and amateur naturalists partake in annual “bioblitzes”;bird watch; butterfly watch; heron watch; and dragonfly watch events (Fig.16),c) Greening of Schools for Biodiversity which provides hands-on experience for students to carry out biodiversity surveys,document biodiversity,and enhance habitats around their school environs,d) maintaining a biodiversity database and atlas for Singapore and allowing members of the public to easily contribute to biodiversity sightings through the use of a mobile application,“SGBioAtlas”,and e) organizing an annual celebration of biodiversity known as the Festival of Biodiversity (FOB),in order to spread knowledge about Singapore's natural heritage and biodiversity to the heartland community.

NParks organised activities from 18 May to 26 May 2019,culminating in the FOB.More than 3,300 participants took part in the nation-wide“bioblitz”,covering more than 90 sites,including our marine park.

There are also numerous community-based platforms for the public to involve themselves in greening and biodiversity conservation,including Community in Bloom,Friends of Ubin Network(FUN),Pesta Ubin,and Friends of the Parks.Together,these various programmes and platforms allow for a broad and deep engagement with Singaporeans across all demographic groups.NParks also encourages active participation in projects and even the employees of corporate sponsors participate as hands-on volunteers in the projects they fund.

4 Monitoring Success—Singapore Index on Cities’ Biodiversity

NParks is the national focal point for the United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity(CBD).In order to track our own success in greening and biodiversity conservation and to support other cities in establishing a common set of indicators for success,we have worked with the secretariat of the CBD in collaboration with the Global Partnership on Sub-National Governments and Cities for Biodiversity on the development of the City Biodiversity Index.Also known as the Singapore Index on Cities' Biodiversity (SI),this is a self-assessment tool for the evaluation of biodiversity efforts carried out by cities[12].Twentyfive cities worldwide have applied the SI and around 40 cities are in various stages of applying the SI.

5 Resional and International Committments

NParks is also a member of the Singapore delegation to the meetings of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change.Our dedication to cultural heritage is reflected by the inscription of the Singapore Botanic Gardens as Singapore's first World Heritage Site on 4 July 2015 during the 39th session of the World Heritage Committee in Bonn,Germany.In recognition of its significant contributions to biodiversity conservation in Singapore,NParks was named the laureate of the 2017 UNESCO Sultan Qaboos Prize for Environmental Preservation.

Sungei Buloh Wetland Reserve and Bukit Timah Nature Reserve,both managed by NParks,have been designated as ASEAN Heritage Parks.

6 Conclusion

Comprehensive surveys and long-term monitoring reveal that Singapore is endowed with rich native biodiversity.Conserving our Nature Reserves and nature areas,along with the way we manage our parks,Park Connector Network,and streetscape,have secured suitable habitats for native biodiversity to thrive in Singapore.Additionally,by reaching up to the skies with skyrise greenery and vertical green walls,and extending our conservation efforts to the coastal and marine environments,we have added multiple dimensions to the understanding and practice of a biophilic city.

This concurs with the independent assessment by two external parties.Firstly,the Treepedia measures the canopy cover in cities in the form of a Green View index (GVI).Of the first 27 cities that they have analysed,Singapore is second with 29.3% despite being one of the cities with the highest population density.Secondly,Timothy Beatley in his book published in 2016,“Handbook of Biophilic City Planning and Design” devoted one chapter on Singapore in part 2 of the book focussing on “Creating Biophilic Cities:Emerging Global Practice.”

By implementing the NCMP,we have embodied biodiversity conservation as part of the development process,hence,evolving Singapore into a liveable and sustainable biophilic city②.

Notes:

① Citizen Scientists are “Members of the public who are neither academics nor government researchers who participate in scientific research and monitoring and whose outcomes contribute to advancements in scientific knowledge as well as enhancing the public's understanding of science”.

② For more information on the biodiversity conservation efforts for NParks,please refer to:Biodiversity in the City:https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7TlA-wSEwWQ; City in a Garden:https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jLRROkGGBfM;Singapore Biophilic City:Original length:https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XMWOu9xIM_k.

Sources of Figures and Table:

Fig.1~16?NParks; Tab.1 is modified from a table on page 605 of Reference[3].