依據減數分裂相關基因數量判別赫氏球石藻(Emiliania huxleyi)繁殖方式研究

胡永梅, 郭 栗, 楊官品

?

依據減數分裂相關基因數量判別赫氏球石藻()繁殖方式研究

胡永梅, 郭 栗, 楊官品

(中國海洋大學 海洋生命學院, 山東 青島 266003)

繁殖方式是生物重要生物學特征之一。了解生物繁殖方式對遺傳和育種研究具有重要意義。赫氏球石藻()呈世界性分布, 在生態系統中扮演重要角色, 但其繁殖方式未知。本研究用分子系統學方法確定有基因組序列且行有性生殖的真核生物的減數分裂相關基因數量, 建立了“減數分裂相關基因≥19個, 其中減數分裂特異基因≥5個”的有性生殖判別標準; 發現赫氏球石藻具有25個減數分裂相關基因, 包括6個減數分裂特異基因。依據建立的標準判定赫氏球石藻行有性生殖。研究結果將有助于赫氏球石藻生活史和遺傳學研究。

赫氏球石藻(); 減數分裂; 減數分裂相關基因; 繁殖方式

有性生殖是生物重要的生物學特征之一。已有研究表明有性生殖起源于真核生物演化早期[1-2], 與遺傳和育種研究密切相關, 因而備受關注。目前, 有性生殖判定主要有直接記錄和間接判別兩類方法。直接記錄是在顯微鏡下觀察并描述有性生殖過程, 但因有性生殖只發生在生物生活史特定時期, 受環境影響較大, 一般難以記錄, 尤其是單細胞生物。間接判定可依賴減數分裂事件、DNA序列和分子標記重組[3-4]、等位基因相異度[5-6]、轉座子豐富度等[7]。但這些方法要么耗時太多, 要么跨物種使用通用性低。減數分裂是生物行有性生殖的必要事件, 且廣泛存在。Mailk等[8]和Karolina等[9]進行減數分裂相關基因系統學分析, 判別了陰道毛滴蟲()和小球藻()的繁殖方式, 同時開發出依據減數分裂相關基因是否存在的生物繁殖方式判別工具。

減數分裂相關基因(包括減數分裂特異基因)是從不同物種生物中鑒別出來的。物種間可能存在“蛋白不同但功能相似、序列差異大無法確定同源性”等情況。因此, 不是每種有性生殖生物都必須具有在不同物種中鑒定出的所有減數分裂相關基因和減數分裂特異基因。Mailk等[8]依據減數分裂相關基因是否存在開發的判別有性生殖工具箱時, 沒有設置具體的有性生殖相關基因數量。我們曾設置這一判別數量標準, 并對三角褐指藻等微藻的繁殖方式進行了判別。但因當時已知的有性生殖物種基因組序列數據有限, 設置的“行有性生殖必須具有≥19個減數分裂相關基因, 包括≥6個減數分裂特異基因”的判別數量標準[10-11]需要修改完善。近幾年基因組序列越來越豐富, 為修改完善提供了數據基礎。

球石藻(coccolithophore)是一類海洋微藻, 屬定鞭藻門(Haptophyta)[12], 其生活史特定階段可形成碳酸鈣質地的球石粒(coccolith), 因此得名[13]。赫氏球石藻()是中最受關注并被廣泛研究的一種, 1858年在深海沉積物中首次記錄, 但其球石粒質地1902年才闡明[14]。從熱帶到亞極地, 從遠洋區到淺海區, 赫氏球石藻都有分布[13]。赫氏球石藻可引發大規模赤潮[15-17], 伴隨大規模有機碳沉積[18-19]。赫氏球石藻攝取大氣CO2鈣化自身, 緩解溫室效應, 固定CO2[20-22]。因此, 赫氏球石藻在海洋碳循環中扮演極其重要角色。赫氏球石藻也被認為是方解石最主要的生產者[23]。

赫氏球石藻細胞形態多樣, 有C細胞(不運動且覆蓋著球石粒)、N細胞(不運動且裸露)和S細胞(運動且覆蓋球石粒)[14, 24-26]。S細胞曾被認為是配子[25-26]。這三類細胞都有無性生殖并形成集群的能力。S細胞DNA含量是C細胞的一半[13-14]。人們認為S細胞是單倍體, 而C細胞是二倍體[15], N細胞也是二倍體。赫氏球石藻單倍體和二倍體細胞形態差異明顯, 生理學和遺傳特性各異[25]。單倍體細胞光敏性較高[24], 不易受感染, 而二倍體細胞易被感染[27]。有人推斷可能是減數分裂產生了單倍體細胞, 以抵抗病毒感染, 被比喻為“柴郡貓逃跑策略(Cheshire cat escape strategy)”[27]。單倍體和二倍體細胞轉錄組也差異顯著, 只有不到50%的相同轉錄本[28-29]。遺憾的是, 赫氏球石藻有性生殖過程從未被記錄過, 也沒有用其他方法判別過。因此, 赫氏球石藻是否存在有性生殖至今尚未徹底闡明。

本研究用分子系統學方法確定有基因組測序且行有性生殖的真核生物的減數分裂相關基因數量, 首先建立了行有性生殖必須具有的減數分裂相關基因, 包括減數分裂特異基因數的判別標準, 然后判別了赫氏球石藻繁殖方式, 以期促進其生物學和遺傳改良研究。

1 材料與方法

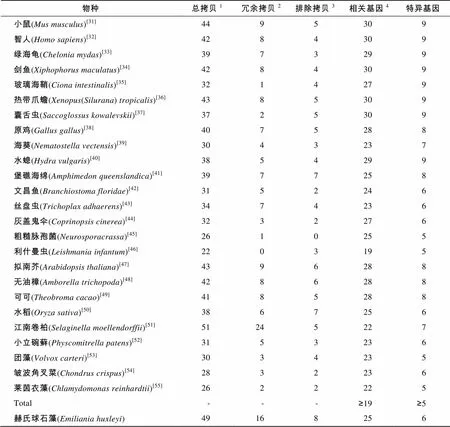

Ramesh等[10]羅列了17個減數分裂相關基因。Malik等[8]將減數分裂相關基因擴展到30個, 其中包括9個減數分裂特異基因。本研究: (1)下載了截止2015年7月的減數分裂相關蛋白, 更新了Malik等[8]判別有性生殖工具箱的減數分裂相關蛋白, 重構了這些蛋白的分子系統學樹; (2)下載了已知行有性生殖的25個物種的基因組序列, 用本地BLAST工具, 據E-value 2 結果 基于E-value 分析發現赫氏球石藻基因組中共有49個序列完整、具有特征結構域的減數分裂相關基因拷貝。該藻減數分裂相關基因拷貝冗余現象非常突出, 僅次于(16︰24)。經過分子系統學分析, 在赫氏球石藻基因組中共發現25個減數分裂相關基因, 其中包括6個減數分裂特異基因(表1, 圖1)。依據本研究建立的判定標準, 赫氏球石藻可進行減數分裂, 營有性生殖。 3 討論 本研究曾設置“行有性生殖必須具有≥19個減數分裂相關基因, 包括≥6個減數分裂特異基因”的有性生殖判定標準[10-11], 但依據的物種數較少。本研究中, 基于現有已知行有性生殖的物種的基因組, 將這一標準修改為“≥19個相關基因和≥5個特異基因”。由于使用的物種具有了足夠寬的代表性, 這一標準應該不會再有改變。減數分裂相關基因(包括減數分裂特異基因)是從不同種生物中鑒別出來的, 而物種間可能存在“蛋白不同但功能相似、序列差異大無法確定同源性”等情況。因此, 這些基因存在與否僅僅依據序列及結構域完整和分子系統學歸宿。當真實有性生殖過程難以記錄時, 該方法是判定是否存在有性生殖的分子生物學方法之一, 可促進相關物種的基礎生物學研究。但最終證實是否存在有性生殖仍需要有性生殖過程描述和其他證據支持。另外, 分子系統學分析確定的有性生殖相關基因或特異基因還需要功能確認。研究發現赫氏球石藻具有30個減數分裂相關基因中的25個, 其中包括9個減數分裂特異基因的6個。依據本研究建立的判定標準, 該藻應具有減數分裂能力, 行有性生殖。 表1 已知存在有性生殖物種和繁殖方式未知的赫氏球石藻基因組中減數分裂相關基因統計 Tab.1 Copy number of meiosis associating genes in known sexually propagating species and 物種總拷貝1冗余拷貝2排除拷貝3相關基因4特異基因 小鼠(Mus musculus)[31]4495309 智人(Homo sapiens)[32]4284309 綠海龜(Chelonia mydas)[33]3973299 劍魚(Xiphophorus maculatus)[34]4284309 玻璃海鞘(Ciona intestinalis)[35]3214279 熱帶爪蟾(Xenopus(Silurana) tropicalis)[36]4385309 囊舌蟲(Saccoglossus kowalevskii)[37]3725309 原雞(Gallus gallus)[38]4075288 海葵(Nematostella vectensis)[39]3043237 水螅(Hydra vulgaris)[40]3854299 堡礁海綿(Amphimedon queenslandica)[41]3977258 文昌魚(Branchiostoma floridae)[42]3152246 絲盤蟲(Trichoplax adhaerens)[43]3474236 灰蓋鬼傘(Coprinopsis cinerea)[44]3232276 粗糙脈孢菌(Neurosporacrassa)[45]2610255 利什曼蟲(Leishmania infantum)[46]2203195 擬南芥(Arabidopsis thaliana)[47]4396288 無油樟(Amborella trichopoda)[48]4286288 可可(Theobroma cacao)[49]4185288 水稻(Oryza sativa)[50]3867256 江南卷柏(Selaginella moellendorffii)[51]51245227 小立碗蘚(Physcomitrella patens)[52]3153236 團藻(Volvox carteri)[53]3034235 皺波角叉菜(Chondrus crispus)[54]2832236 萊茵衣藻(Chlamydomonas reinhardtii)[55]2622225 Total---≥19≥5 赫氏球石藻(Emiliania huxleyi)49168256 注:1.氨基酸序列完整, 具有特定結構域的基因拷貝總數;2.系統學分析被確定為相同基因拷貝, 一個計為減數分裂相關基因, 其余記為冗余拷貝;3.系統學分析不能確定為減數分裂相關基因;4.包含特異基因 基因組遺傳物質加倍現象廣泛存在于自然界中。加倍過程主要通過非依賴機制進行, 這些機制包括DNA復制和重組過程等。在加倍過程中, 遺傳物質的加倍程度亦有所區別, 在DNA復制和重組過程中遺傳物質發生串聯加倍和片段加倍, 而運用其他方法可使整個基因組序列加倍, 從而產生多倍體[56]。其中備受學者關注的是基因加倍。最近相關觀點認為基因加倍對植物的多樣性具有重要意義, 其關鍵過程是產生植物適應性進化所必須的原材料[57]。因此減數分裂相關基因的加倍也影響著減數分裂基因的進化和對其基因功能的評估。理論推測加倍基因的進化主要有三種途徑: (1)一個拷貝由于退化突變造成基因沉默, 從而成為假基因(即基因的無功能化); (2)一個基因拷貝仍然保持原有功能, 而另一個基因拷貝可能獲得一個新的, 有益的功能并由于自然選擇而保留下來成為新功能基因(即新功能化); (3)兩個基因拷貝可能由于突變的累積, 使得這兩個拷貝的功能逐漸退化到二者總的功能相當于其單拷貝祖先基因的水平(即亞功能化)[58]。例如赫氏球石藻存在的2個同源蛋白基因, 經分子系統學分析, 將二者全部排除在減數分裂相關功能之外。這些基因拷貝可能已經演變成為假基因, 也可能正在演變成為新功能基因。由于許多減數分裂基因具有有絲分裂的旁系同源基因(比如,和), 同時這些基因之間擁有著數量眾多的相似性序列。但通過分子系統學分析可以清楚的區別出減數分裂相關基因的旁系基因。例如, 通過分子系統學所構建的樹形系統樹可以將減數分裂相關的同源基因,與無減數分裂功能的同源基因分開, 并將赫氏球石藻中存在的3個同源基因的拷貝區別開, 1個拷貝編碼Spo11-2, 另外2個拷貝編碼Spo11-3。,等亦存在多個同源基因的拷貝。然而這些拷貝是否具有減數分裂相關功能、具有何種功能, 需進一步的研究。赫氏球石藻中的2個Rad50同源蛋白融入Rad50兩個不同的小進化分支中, 這可能是由于在基因加倍的過程中, 同一基因的堿基序列出現差異或是同一基因所編碼氨基酸序列出現差異, 也可能是在物種進化過程中兩個基因出現趨同進化所造成的。這些推測需要進一步的研究和確定。 A. Msh2, Msh3, Msh4, Msh5和Msh6; B. Mad2和Hop1; C. Rad51和Dmc1, 根置于古菌RadA; D. Mnd1和Hop2; E. Spo11 A. Msh2, Msh3, Msh4, Msh5, and Msh6; B. Mad2 and Hop1; C. Rad51 and Dmc1 rooted into archaeal RadA; D. Mnd1 and Hop2; E. Spo11 雖然現階段判定有性生殖的方法繁多, 例如顯微鏡觀察, DNA序列和標記重組[3-4]、等位基因相異度[5-6]等, 但仍無法避免實驗周期較長, 跨物種使用困難的固有缺點。運用群體遺傳學方法, 則需大量個體及多樣的地理來源, 在實際運用過程中也存在一定的局限。隨著測序技術的發展和完善, 基因組測序變得迅速而高效。依據蛋白序列相似性及結構域保守性等, 通過搜索基因組相關序列可迅速地在最大程度上發現和了解已標識的減數分裂相關蛋白。依據一組減數分裂相關基因(包括減數分裂特異基因), 運用分子系統學分析方法, 可強烈支持有性生殖的存在, 這就提高了赫氏球石藻存在有性生殖的可信度。雖然無法驗證這些基因是否具有減數分裂相關功能, 但是可以進一步借助其他分子生物學方法, 例如基因敲除, 遺傳互補分析等直接進行驗證。 赫氏球石藻具有單、雙倍體生活史。Aude等經流式細胞儀分析發現4種球石藻(包括赫氏球石藻)存在兩種倍性, 并認為異型球石粒是二倍體向單倍體轉換的階段[24]。本研究的分析結果使赫氏球石藻存在有性生殖的可能性大大提高。有性生殖可有效減少有害突變積累, 有利于物種進化, 可提高物種環境適應性。本研究判定赫氏球石藻具有行有性生殖能力, 但減數分裂和配子融合未直接觀察到。因此, 加強對赫氏球石藻有性生殖過程的追蹤, 徹底認識其繁殖方式, 不僅是闡明赫氏球石藻完整生活史的需要, 也是其遺傳改良研究的需要。 [1] Schurko A M, Logsdon J M. Using a meiosis detection toolkit to investigate ancient asexual scandals and the evolution of sex[J]. Bioessays, 2008, 30(6): 579-589. [2] Ramesh M A, Malik S B, Logsdon J M. A phylogenomic inventory of meiotic genes: Evidence for sex inand an early eukaryotic origin of meiosis[J]. Current Biology, 2005, 15(2): 185-191. [3] Geiser D M, Pitt J I, Taylor J W. Cryptic speciation and recombination in the aflatoxin producing fungus[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 1998, 95(1): 388-393. [4] Litvintseva A P, Thakur R, Vilgalys R, et al. Multilocus sequence typing reveals three genetic subpopulations ofvar.(serotype A), including a unique population in Botswana[J]. Genetics, 2006, 172(4): 2223-2238. [5] Welch D B M, Meselson M. Evidence for the evolution of bdelloid rotifers without sexual reproduction or genetic exchange[J]. Science, 2000, 288(5469): 1211-1215. [6] Birky C W. Heterozygosity, heteromorphy, and phylogenetic trees in asexual eukaryotes[J]. Genetics, 1996, 144(1): 427-437. [7] Wright S, Finnegan D. Genome evolution: Sex and the transposable element[J]. Current Biology, 2001, 11(8): R296-R299. [8] Malik S B, PightlingA W, Stefaniak L M, et al. An expanded inventory of conserved meiotic genes provides evidence for sex in[J]. PLoS ONE, 2008, 3(8): e2879. [9] Fu?íková K, Pa?outová M, Rindi F. Meiotic genes and sexual reproduction in the green algal class Trebouxiophyceae (Chlorophyta)[J]. Journal of Phycology, 2015, 51(3): 419-430. [10] Guo L, Yang G. Predicting the reproduction strategies of several microalgae through their genome sequences[J]. Journal of Ocean University of China, 2014, 14(3): 491-502. [11] 郭栗, 楊官品. 依據減數分裂特異基因判定三角褐指藻生殖方式的研究[J]. 中國海洋大學學報(自然科學版), 2013, 43(12): 41-47. [12] Falkowski P G, Knoll A H. Evolution of primary producers in the sea[M]. California: Elsevier Academic Press, 2007: 251-285. [13] Medlin L K, Barker G L A, Campbell L, et al. Genetic characterisation of(Haptophyta)[J]. Journal of Marine Systems, 1996, 9(1): 13-31. [14] Green J C, Course P A, Tarran G A. The life-cycle of: A brief review and a study of relative ploidy levels analysed by flow cytometry[J]. Journal of Marine Systems, 1996, 9(1): 33-44. [15] Laguna R, Romo J, Read B A, et al. Induction of phase variation events in the life cycle of the marine coccolithophorid[J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2001, 67(9): 3824-3831. [16] Brown C W, Yoder J A. Coccolithophorid blooms in the global ocean[J]. Journal of Geophysical Research, 1994, 99(C4): 7467-7482. [17] Holligan P M, Fernández E, Aiken J, et al. A biogeochemical study of the coccolithophore,, in the North Atlantic[J]. Global Biogeochemical Cycles, 1993, 7(4): 879-900. [18] Westbroek P, De Jong E W, Van Der Wal P, et al. Mechanism of calcification in the marine alga[J]. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, 1984, 304(1121): 435-444. [19] Coxall H K, Wilson P A, P?like H, et al. Rapid stepwise onset of Antarctic glaciation and deeper calcite compensation in the Pacific Ocean[J]. Nature, 2005, 433(7021): 53-57. [20] Riebesell U, K?rtzinger A, Oschlies A. Sensitivities of marine carbon fluxes to ocean change[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 2009, 106(49): 20602-20609. [21] Gattuso J P, Hansson L. Ocean acidification[M]. New York: Oxford University Press, 2011: 99-121. [22] Westbroek P, Brown C W, Van Bleijswijk J, et al. A model system approach to biological climate forcing: The example of[J]. Global and Planetary Change, 1993, 8(1): 27-46. [23] Robertson J E, Robinson C, Turner D R, et al. The impact of a coccolithophore bloom on oceanic carbon uptake in the northeast Atlantic during summer 1991[J]. Deep Sea Research Part I: Oceanographic Research Papers, 1994, 41(2): 297-314. [24] Houdan A, Billard C, Marie D, et al. Holococcolithophore-heterococcolithophore (Haptophyta) life cycles: Flow cytometric analysis of relative ploidy levels[J]. Systematics and Biodiversity, 2004, 1(4): 453-465. [25] Paasche E, Klaveness D.A physiological comparison of coccolith-forming and naked cells of[J]. Archives of Microbiology, 1970, 73(2): 143-152. [26] Klaveness D.(Lohm.) Kamptn II. The flagellate cell, aberrant cell types, vegetative propagation and life cycles[J]. British Phycological Journal, 1972, 7(3): 309-318. [27] Frada M, Probert I, Allen M J, et al. The Cheshire Cat escape strategy of the coccolithophorein response to viral infection[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 2008, 105(41): 15944- 15949. [28] Rokitta S D, De Nooijer L J, Trimborn S, et al. Transcriptome analyses reveal differential gene expression patterns between the life-cycle stages of(Haptophyta) and reflect specialization to different ecological niches[J]. Journal of phycology, 2011, 47(4): 829-838. [29] Von Dassow P, Ogata H, Probert I, et al. Transcriptome analysis of functional differentiation between haploid and diploid cells of, a globally significant photosynthetic calcifying cell[J]. Genome Biology, 2009, 10(10): R114. [30] Read B A, Kegel J, Klute M J, et al. Pan genome of the phytoplanktonunderpins its global distribution[J]. Nature, 2013, 499(7457): 209-213. [31] Chinwalla A T, Cook L L, Delehaunty K D, et al. Initial sequencing and comparative analysis of the mouse genome[J]. Nature, 2002, 420(6915): 520-562. [32] Lander E S, Linton L M, Birren B, et al. Initial sequencing and analysis of the human genome[J]. Nature, 2001, 409(6822): 860-921. [33] Wang Z, Pascual-Anaya J, Zadissa A, et al. The draft genomes of soft-shell turtle and green sea turtle yield insights into the development and evolution of the turtle-specific body plan[J]. Nature Genetics, 2013, 45(6): 701-706. [34] Schartl M, Walter R B, Shen Y, et al. The genome of the platyfish,, provides insights into evolutionary adaptation and several complex traits[J]. Nature Genetics, 2013, 45(5): 567-572. [35] Dehal P, Satou Y, Campbell R K, et al. The draft genome of: Insights into chordate and vertebrate origins[J]. Science, 2002, 298(5601): 2157-2167. [36] Hellsten U, Harland R M, Gilchrist M J, et al. The genome ofthe western clawed frog[J]. Science, 2010, 328(5978): 633-636. [37] Lowe T M, Eddy S R. tRNAscan-SE: A program for improved detection of transfer RNA genes in genomic sequence[J]. Nucleic Acids Research, 1997, 25(5): 955-964. [38] Hiller L W, Miller W, Birney E, et al. Sequence and comparative analysis ofthe chicken genome provide uniqueperspectives on vertebrate evolution[J]. Nature, 2004, 432(7018): 695-716. [39] Putnam N H, Srivastava M, Hellsten U, et al. Sea anemone genome reveals ancestral eumetazoan gene repertoire and genomic organization[J]. Science, 2007, 317(5834): 86-94. [40] Chapman J A, Kirkness E F, Simakov O, et al. The dynamic genome of[J]. Nature, 2010, 464(7288): 592-596. [41] Srivastava M, Simakov O, Chapman J, et al. Thegenomeand the evolution of animal complexity[J]. Nature, 2010, 466(7307): 720- 726. [42] Putnam N H, Butts T, Ferrier D E K, et al. The amphioxus genome and the evolutionof the chordate karyotype[J]. Nature, 2008, 453(7198): 1064-1071. [43] Srivastava M, Begovic E, Chapman J, et al. Thegenome and the nature of placozoans[J]. Nature, 2008, 454(7207): 955-960. [44] Stajich J E, Wilke S K, Ahrén D, et al. Insights into evolution of multicellular fungi from theassembled chromosomes of the mushroom()[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 2010, 107(26): 11889-11894. [45] Galagan J E, Calvo S E, Borkovich K A, et al. The genome sequence of the filamentous fungus[J]. Nature, 2003, 422(6934): 859-868. [46] Peacock C S, Seeger K, Harris D, et al. Comparative genomic analysis of threespecies that cause diverse human disease[J]. Nature Genetics, 2007, 39(7): 839-847. [47] Arabidopsis Genome Initiative. Analysis of the genome sequence of the flowering plant[J]. Nature, 2000, 408(6814): 796-815. [48] Amborella Genome Project. Thegenome and the evolution of flowering plants[J]. Science, 2013, 342(6165). [49] Argout X, Salse J, Aury J M, et al. The genome of[J]. Nature Genetics, 2011, 43(2): 101- 108. [50] Goff S A, Ricke D, Lan T H, et al. A draft sequence of the rice genome (L. ssp.)[J]. Science, 2002, 296(5565): 92-100. [51] Banks J A, Nishiyama T, Hasebe M, et al. Thegenome identifies genetic changes associated with the evolution of vascular plants[J]. Science, 2011, 332(6032): 960-963. [52] Rensing S A, Lang D, Zimmer A D, et al. Thegenome reveals evolutionary insights into the conquest of land by plants[J]. Science, 2008, 319(5859): 64-69. [53] Prochnik S E, Umen J, Nedelcu A M, et al.Genomic analysis of organismal complexity in the multicellular green alga[J]. Science, 2010, 329(5988): 223-226. [54] Collén J, Procel B, Carré W, et al. Genome structure and metabolic features in the red seaweedshed light on evolution of the Archaeplastida[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 2013, 13(110): 5247-5252. [55] Merchant S S, Prochnik S E, Vallon O, et al.Thegenome reveals the evolution of key animal and plant functions[J]. Science, 2007, 318(5848): 245-250. [56] Ramsey J, Schemske D W. Pathways, mechanisms, and rates of polyploid formation in flowering plants[J]. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics, 1998, 29: 467-501. [57] Flagel L E, Wendel J F. Gene duplication and evolutionary novelty in plants[J]. New Phytologist, 2009, 183(3): 557-564. [58] Lynch M, Conery J S. The evolutionary fate and consequences of duplicate genes[J]. Science, 2000, 290(5494): 1151-1155. (本文編輯: 康亦兼) Ascertaining the reproduction strategy ofby numbering its meiosis-associated genes HU Yong-mei, GUO Li, YANG Guan-pin (College of Marine Life Sciences, Ocean University of China, Qingdao 266003, China) Reproduction strategy is one of the most important biological characteristics of an organism. Ascertaining such a strategy is crucial for its genetic research and improvement.plays a key role in the ocean ecosystem, but nothing is known about its reproductive strategy. Here, we numbered the meiosis-associated genes of sexually reproductive eukaryotes with genome sequences that were available and found that they held ≥19 meiosis-associated genes, of which ≥5 were meiosis-specific. We also found thatcontained 25 meiosis-associated genes, of which 6 were meiosis-specific. Based on this information, we concluded thatperforms sexual reproduction. This ascertainment may aid to studying its life cycle and genome and further its genetic improvement. Nov.17, 2015 ; meiosis; meiosis-associated gene; reproductive strategy Q178.53 A 1000-3096(2016)06-0001-07 10.11759/hykx20151117002 2015-11-17; 2016-02-05 國家自然科學基金(3127408) [Foundation: National Natural Science Foundation of China, No.3127408] 胡永梅(1989-), 女, 山東青島人, 碩士研究生, 主要從事海洋微藻研究, 電話: 18561538935, E-mail: xiaoping0331hu@163.com; 楊官品, 通信作者, 教授, 博士生導師, 電話: 0532-82031636, E-mail: yguanpin@mail.ouc.edu.cn

Guo L, Yang Guanpin. Study on the determination ofreproduction strategy with the presence of meiosis-specific genes[J]. Periodical of Ocean University of China, 2013, 43(12): 41-47.