抗菌藥物神經毒性的機制及危險因素研究進展

熊立廣?李昕?向德標?袁芳?童煥

摘要:抗菌藥物作為治療及預防細菌感染的特效藥,在臨床上被廣泛使用,同時也存在一系列的副作用。其中,神經毒性是抗菌藥物臨床使用過程中最常見的一種嚴重且易混淆的毒副作用。本文就抗菌藥物神經毒性的臨床癥狀、作用機制、危險因素以及防治措施進行總結,為抗菌藥物臨床合理用藥及有效防治抗菌藥物的神經毒性提供科學依據。

關鍵詞:抗菌藥物;神經毒性;機制;危險因素;防治措施

中圖分類號:R978.1文獻標志碼:A

Research progress on the mechanism and risk factors of antibiotics neurotoxicity

Xiong Li-guang1,2, Li Xin2,3, Xiang De-biao2,3, Yuan Fang2,3, and Tong Huan2,3

(1 Hunan University of Chinese Medicine, Changsha 410015; 2 The Third Hospital of Changsha, Changsha 410015;

3 Antibiotic Clinical Application Research Institute of Changsha, Changsha 410015)

Abstract Antibacterial agents are widely used clinically for the treatment and prevention of bacterial infections while a range of adverse effects exist. Neurotoxicity is one of the most common, serious, and confusing side effects in the clinical use of antibiotics. In this article, the clinical symptoms, mechanism of action, risk factors, and preventive measures of neurotoxicity of antibiotics are summarized to provide a scientific basis for the rational application of antibacterial drugs in clinical practice and the effective prevention and treatment of the neurotoxicity of antibiotics.

Key words Antibacterial agents; Neurotoxicity; Mechanism; Risk factors; Prevention

隨著全球微生物感染疾病的肆虐及傳播,抗菌藥物的使用日益廣泛,其毒性也逐漸受到人們的重視。抗菌藥物的毒性主要表現為腎毒性、神經毒性、肝毒性等。其中神經毒性呈濃度依賴性,且隨著藥物劑量的調整其神經毒性是可逆的,停藥后可恢復。但往往在治療中會與不同的神經病征或患者本身罹患疾病混淆,同時存在著老齡、腎功能不全以及既往病史等危險因素,導致抗菌藥物難以合理使用,造成進一步神經損害[1]。抗菌藥物神經毒性產生機制比較廣泛,主要與GABA(γ-氨基丁酸)、NMDA(N-methyl-D-aspartic acid, N-甲基-D-天冬氨酸)受體、乙酰膽堿等神經遞質的損傷相關,同時也與氧化應激以及線粒體功能障礙關系密切。目前針對抗菌藥物神經毒性的防治措施除停藥外,也采用藥物進行預防或控制神經毒性癥狀的發生,如增強GABAA活性的苯二氮卓類藥物,具有神經保護作用的谷胱甘肽、神經節苷脂、雷帕霉素和紅景天苷等,同時越來越多的藥物臨床使用建議采用TDM(治療藥物血藥濃度監測)來制定個體化給藥方案,以此優化抗菌藥物的合理應用。

1 抗菌藥物神經毒性的臨床表現

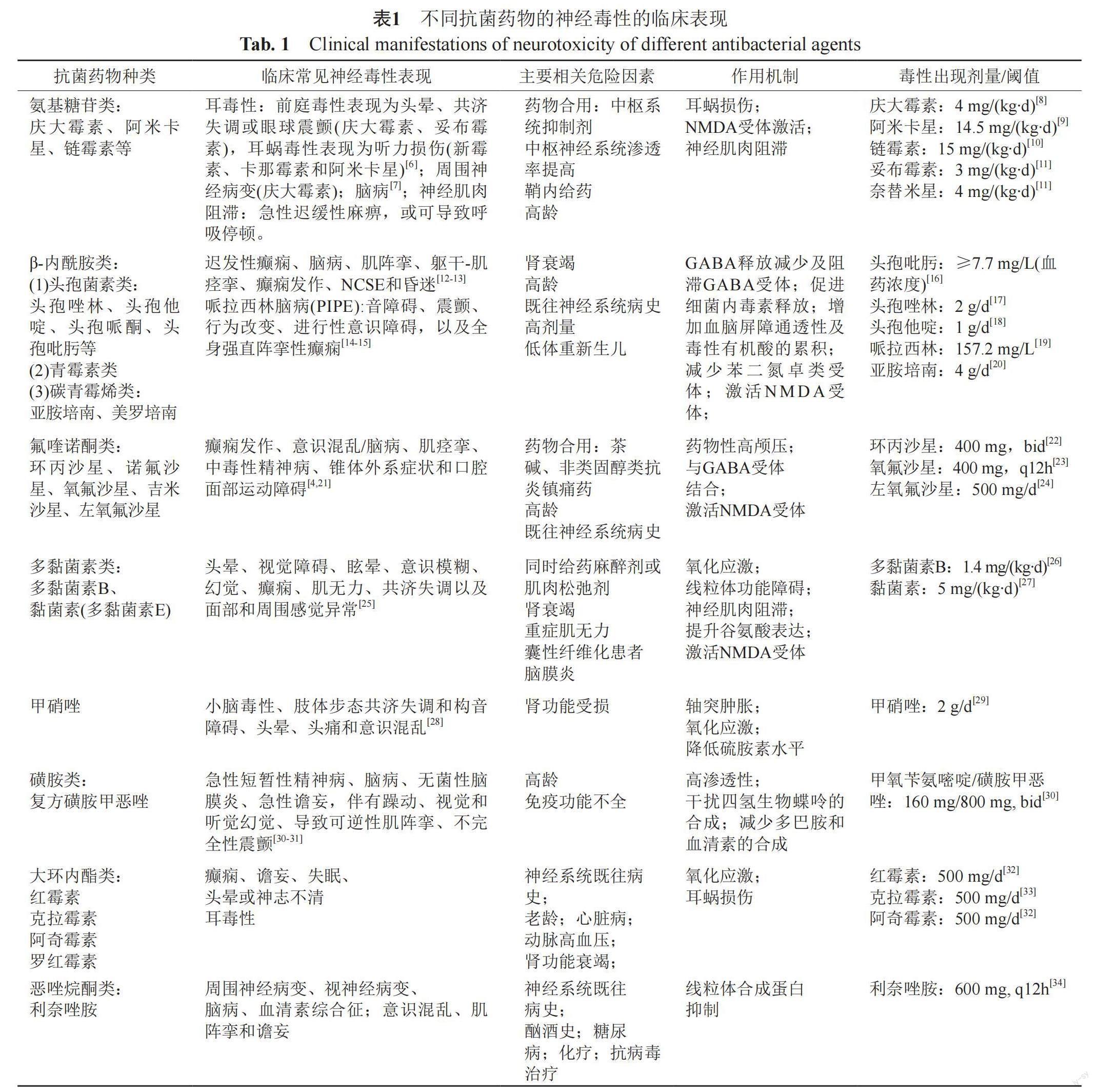

臨床上評估神經毒性主要通過相關生化指標、腦電圖表現、心理和行為測試和神經學檢查等途徑。抗菌藥物臨床癥狀表現多樣,且不同抗菌藥物的神經毒性臨床表現有所不同,分為中樞神經毒性以及周圍神經毒性。中樞神經毒性主要表現為以精神狀態改變、記憶喪失、激動、認知能力喪失、失眠和幻覺為特征的腦病[2]、耳毒性、視覺和聽覺幻覺、癲癇發作、非驚厥性癲癇持續狀態(nonconvulsive epileptic, NCSE)和昏迷[3];周圍神經毒性主要表現為口腔面部運動障礙、肌陣攣與肌無力[4-5],詳見表1。

2 抗菌藥物神經毒性發生機制

抗菌藥物產生神經毒性的機制主要有以下幾種:①與γ-氨基丁酸(GABA)結合減少,或直接拮抗GABAA受體阻斷GABA結合位點,導致抑制性神經遞質濃度降低和皮質傳入興奮,從而導致神經傳遞過度興奮誘發神經毒性[21,35];②激活NMDA受體,造成神經興奮、ROS生成增加和Ca2+胞內濃度升高,誘導細胞凋亡[36-38];③軸突變性[39-40];④抑制乙酰膽堿突觸前釋放,阻滯或減弱乙酰膽堿與受體的結合[41-42];⑤鈣離子消耗引起的去極化[43];⑥氧化應激以及線粒體功能障礙[25]。

2.1 氨基糖苷類

氨基糖苷類藥物誘發神經毒性以耳毒性最為常見,同時也有研究報道氨基糖苷類的周圍神經系統損傷、腦病以及神經肌肉阻滯等相關神經毒性。

(1)耳毒性? ? 氨基糖苷類藥物造成的耳毒性包括耳蝸損傷和前庭器官損傷,耳毒性整體發生率范圍在2%~25%[44-45]。氨基糖苷類產生耳毒性的機制為氨基糖苷類藥物進入內耳后透過賴斯納氏膜、血管紋以及基底膜等結構進入耳蝸,主要在靜纖毛的機械力電轉導作用下(次要途徑為內吞作用和基底外側TRPA1通道)進入毛細胞[46-50],并與毛細胞中tRNA結合,導致線粒體的RNA翻譯受損以及蛋白質合成抑制,減少ATP的產生[51-52],從而促進活性氧的生成,破壞線粒體的完整性,促進細胞色素C的釋放,激活細胞凋亡級聯反應[36,53]。同時研究表明氨基糖苷類藥物能夠激活耳蝸內NMDA受體,而過度激活NMDA受體會增加一氧化氮(NO)的形成,從而促進活性氧的產生,同時可能增加Ca2+通過NMDA受體進入細胞,誘導急性腫脹破壞突觸后結構,隨后導致鈣離子級聯反應,進一步導致神經元細胞凋亡和損傷[36,54]。

(2)神經肌肉阻滯? ? 氨基糖苷類藥物的神經肌肉阻滯機制多樣,如新霉素能阻滯Ca2+通道從而抑制突觸前乙酰膽堿的釋放;氨基糖苷類藥物如慶大霉素和新霉素還能通過阻滯Ca2+進入膽堿能受體來抑制毛細胞中的膽堿能K+電流傳導,誘導神經肌肉阻滯[55-56]。也有研究表明氨基糖苷類藥物能促進對乙酰膽堿受體(AChR,acetycholine report)的免疫應答,提高血清中AChR抗體水平,阻斷ACh與受體的結合,加速肌肉神經接點上AChR的丟失,破壞突觸前和突觸后膜結構從而誘導神經肌肉阻滯[57]。

2.2 β-內酰胺類

(1)頭孢菌素類? 頭孢素類藥物中第一代頭孢菌素(頭孢唑林)、第二代頭孢菌素(頭孢呋辛)、第三代頭孢菌素(頭孢他啶)以及第四代頭孢菌素(頭孢吡肟)都有神經毒性的相關報道。根據藥物警戒數據庫對1987—2017年的病例統計分析,各類頭孢菌素類藥物的神經毒性發生率分別為:頭孢吡肟(33.1%)、頭孢曲松(29.7%)、頭孢他啶(19.6%)、頭孢噻肟(9%)和頭孢唑林(2.9%)[58]。頭孢菌素類藥物造成神經毒性的主要機制有以下方面:①減少神經末梢釋放γ-氨基丁酸(GABA),同時與GABA-A受體競爭性結合抑制GABA誘導的Cl-電流,導致神經元過度興奮和突觸后膜去極化,降低癲癇發作閾值[59-61]。值得注意的是,青霉素與GABA受體的結合是非競爭性的,意味著頭孢菌素類更可能發生神經毒性[62]。②頭孢他啶能誘導革蘭陰性菌細胞釋放內毒素,如LPS,而LPS能夠造成小膠質細胞的激活,釋放TNF-a和IL-1β,同時頭孢他啶本身也能提升促炎細胞促進因子的轉錄,如TNF-α和IL-6等,這些細胞因子能夠誘導神經元細胞的凋亡和損傷[63-64]。③在腎功能不全的患者中,頭孢吡肟隨著肌酐清除率的降低而排泄減少,而高血漿濃度的頭孢吡肟能夠介導血尿素增加、氨甲酰化、糖基化或其他化學蛋白修飾,導致血腦屏障通透性增加以及腦脊液毒性有機酸的積累[65]。④研究表明使用微透析技術將頭孢噻利注入海馬體后,實驗大鼠的神經元細胞外谷氨酸顯著升高,盡管該項研究結果表明頭孢噻利誘導神經毒性的機制更傾向于GABA受體的阻滯,但多項研究也表明谷氨酸的過度釋放能引起神經功能障礙和退化,提示谷氨酸介導的興奮作用可能作為潛在的機制誘導神經毒性[66-68]。

(2)青霉素類 青霉素類藥物誘導神經毒性的機制主要為:①研究表明青霉素在毫摩爾濃度下能阻滯GABA-A受體的電壓依賴性離子通道(voltage-dependent channel),減少GABA與受體的結合,從而降低抑制信號傳遞,使神經元過度興奮發生

癲癇[62,69]。②高劑量青霉素能夠減少苯二氮卓受體,從而降低抑制和改變神經元興奮性[70]。

(3)碳青霉烯類? 碳青霉烯類藥物神經毒性常表現為癲癇發作,其中亞胺培南的癲癇發作率在3%~33%之間,而多利培南和厄他培南則小于1%[71]。該類藥物造成神經毒性的機制主要有:①與GABA-A受體結合并抑制,碳青霉烯類藥物分子的側鏈堿性越強,與GABA-A受體的親和力越高,其致癲癇潛能就越大,美羅培南的C2側鏈比亞胺培南和帕尼培南的堿性小得多,因此前者的神經毒性小于后者[72];②與NMDA受體結合造成興奮性毒性[73];③與α-氨基-3-羥基-5-甲基異惡唑-4-丙酸受體的結合也被認為與癲癇發作有關[74]。

2.3 氟喹諾酮類

研究表明左氧氟沙星和環丙沙星為氟喹諾酮類藥物中最常見引起神經毒性的藥物[3-4,75-76]。氟喹諾酮類藥物的神經系統滲透性與其致癲癇性并不完全相關,有報道稱與環丙沙星相比,氧氟沙星的神經系統滲透濃度較高,能達到血清中濃度的50%,但后者相比前者,其臨床神經毒性的報道較少[77-78]。氟喹諾酮類藥物造成神經毒性的機制主要有:①氟喹諾酮類藥物的母核上6位的氟原子具有疏水性,脂溶性較好,易滲透進血腦屏障進入腦組織,藥物濃度過高會增加細胞滲透壓,使神經元細胞水腫導致藥物性高顱壓[79];②氟喹諾酮類藥物上的7-哌嗪環與GABA結構相似,能與GABA-A受體結合阻滯GABA傳遞抑制性神經電流,導致神經興奮[79-80];③激活NMDA受體使神經興奮[37]。

2.4 多黏菌素類

多黏菌素類藥物主要包括多黏菌素B和黏菌素(多黏菌素E)。早期研究報道多黏菌素在肌肉注射和靜脈注射給藥后神經毒性的發生率分別約為7.3%和27%[81]。近些年可能由于對給藥劑量及聯合用藥的優化,近期的研究統計表明多黏菌素的神經毒性發生率在0~7%[82]。多黏菌素類藥物造成神經毒性的機制主要有:①氧化應激:黏菌素能顯著提升細胞內活性氧(ROS)水平,降低谷胱甘肽(GSH)水平和抗氧化酶超氧化物歧化酶和過氧化氫酶(CAT)活性,導致脂質、蛋白質和DNA受損,并最終導致神經元細胞死亡而表現為神經毒性[25,83];②線粒體功能障礙:研究表明多黏菌素能夠誘導線粒體中Bax/Bcl-2蛋白比值上升,增加Ca2+誘導的線粒體通透性轉變降低膜電位和降低琥珀酸脫氫酶,使線粒體中超微結構發生病理變化,如嵴破裂以及廣泛腫脹,從而促進細胞色素C的釋放并激活Caspase蛋白相關的凋亡級聯

通路[40,83];③神經肌肉阻滯:多黏菌素能非競爭性地與突觸前受體結合,阻斷乙酰膽堿釋放到突出間隙中,同時研究表明多黏菌素能提高機體內乙酰膽堿酯酶水平,加速乙酰膽堿的降解,從而延長去極化,持續消耗Ca2+,導致神經肌肉阻滯[84-85];④神經興奮:研究表明靜脈注射黏菌素后能顯著提升小鼠大腦皮層中谷氨酸以及NMDA受體的表達,促進Na+和Ca2+內流到神經元導致興奮性毒性[38]。

2.5 甲硝唑

甲硝唑長期使用易導致神經毒性,造成小腦病變,但停藥后3~7 d癥狀會得到緩解[86]。有研究表明甲硝唑造成神經毒性的機制為甲硝唑誘導血管源性水腫繼發的軸突腫脹引起的;也有研究表明甲硝唑能導致脂質過氧化物MDA(丙二醛)的累積,同時誘導體內CAT、SOD水平下降,導致氧化應激失衡,同時該研究還提及甲硝唑能夠降低機體內硫胺素(維生素B1)水平,造成磷酸戊糖代謝障礙,影響磷脂類的合成,使周圍和中樞神經組織出現脫髓鞘和軸索變性樣改變,導致神經元細胞損傷[86-87]。

2.6 磺胺類藥物

研究表明,當甲氧嘧啶的劑量從<12 mg/(kg·d)調高至>18 mg/(kg·d)時,精神病的發生率由0升至23.5%[88]。磺胺類藥物引起神經毒性的機制可能是由于磺胺類藥物具有的神經系統高滲透性,同時甲氧芐啶能抑制二氫葉酸還原酶(DHFR),磺胺甲惡唑為二氫蝶酸合酶的競爭性抑制劑,二者結合能干擾四氫生物蝶呤的合成,從而減少多巴胺和血清素的合成,影響神經系統的信號傳導,導致神經系統的毒副作用[89-90]。

2.7 大環內酯類藥物

大環內酯類藥物主要包括紅霉素及其衍生物(阿奇霉素和克拉霉素),該類藥物的神經毒副作用主要為癲癇、譫妄、頭暈、神志不清以及耳毒性[33,91]。該藥物造成中樞神經系統受損的機制尚不明確,但一篇研究報道了球藻暴露在羅紅霉素時,能造成MDA累積以及SOD和CAT水平的降低,提示大環內酯類藥物可能通過氧化應激的方式對中樞神經系統造成損傷[92]。而耳毒性在報道中認為靜脈注射大劑量大環內酯類藥物時產生,這可能是由血管紋水腫導致外毛細胞功能障礙引起的[93]。

2.8 惡唑烷酮類藥物

利奈唑胺作為惡唑烷酮類藥物的代表藥物,其神經毒副作用主要體現為周圍神經病變、視神經病變、腦病、血清素綜合征;意識混亂、肌陣攣和譫妄[94]。該藥的毒副作用機制目前尚未定論,不過許多研究鑒于利奈唑胺的抗菌機制為通過與50S核糖體亞基結合來抑制細菌蛋白質,普遍支持其神經毒性的機制為抑制線粒體蛋白合成,從而造成后續的骨髓抑制、神經病變和乳酸中毒[95]。

3 抗菌藥物神經毒性的危險因素

3.1 年齡

年齡是抗菌藥物造成神經毒性的主要危險因素之一。老年患者是細菌感染(肺炎、流感和敗血癥)的高發人群,同時老年患者存在不同程度的肝腎功能減退, 機體肌肉含量下降,脂肪含量提高,其藥物動力學(PK)特性發生變化,藥物代謝減緩以及藥物分布發生變化使藥物易于累積,造成血藥濃度增高。此外許多老年患者往往罹患各種較嚴重的基礎疾病,存在不同程度的腦萎縮或腦動脈硬化、中樞神經系統耐受性差、血漿蛋白含量降低等因素。上述原因導致這一人群的神經系統不良反應風險增高[96-98]。

3.2 腎衰竭

在抗菌藥物的誘發的神經毒性中,腎衰竭也是重要的危險因素之一。腎衰竭能從藥代學以及藥效學兩個方面增加抗菌藥物神經毒性的發生風險。

(1)藥代學方面:①腎衰竭中的尿毒癥毒素能降低胃腸道、肝以及腎中的細胞色素P含量,降低藥物代謝酶的活性,從而導致抗菌藥物代謝緩慢造成累積[99];②終末期腎病患者肝組織中P-糖蛋白(P-gp, P-glycoprotein)的藥物外排功能和有機陰離子多肽轉運體(OATP, organic anion transporting polypeptide)介導的藥物攝取轉運蛋白功能都有不同程度的缺陷,從而減少藥物的非腎性消除導致藥物累積[100-101];③腎衰竭導致的低白蛋白血癥(與腎臟疾病中蛋白尿和硫胺素缺乏相關)減少抗菌藥物的蛋白結合,導致血液中抗菌藥物的游離濃度升高,增加中樞神經系統毒性風險[102];④腎衰竭患者往往肌肉和皮下脂肪含量減少,這兩者都會改變親脂性抗菌藥物的藥代動力學特征容積[103];總之,腎功能衰竭能降低抗菌藥物的代謝消除、蛋白結合以及分布,從而導致其神經毒性風險增加。

(2)藥效學方面:腎衰竭導致的電解質紊亂和神經元膜上蛋白質的化學修飾可能會降低癲癇發作的閾值,同時神經遞質受體或其信號通路的化學修飾可能影響廣泛的神經元功能[103]。除此之外,研究表明腎衰竭小鼠中腦脊液中的蛋白質濃度增加,同時尿毒癥會介導涉及rOat3和rOatp2受體的腦-血液運輸受到抑制,導致內源性代謝物和藥物在大腦中積累,這表明腎衰竭能造成血腦屏障的通透性改變或中樞神經系統功能障礙[104-105]。

值得一提的是,碳青霉烯類藥物在腎衰竭誘導的神經毒性機制存在一定的特殊性。一項研究表明,亞胺培南通過非腎消除產生的代謝物能夠導致動物癲癇發作,且這種代謝物在腎衰竭病癥中具有較長的半衰期[106]。另外一項研究則將亞胺培南的神經毒性歸因于其在腦脊液的緩慢消除,該研究認為尿毒癥毒素能競爭性抑制腦脊液的主動外排轉運機制,因此在腎衰竭的情況下,毒性有機酸的積累或pH值的改變可能會導致亞胺培南(以及青霉素和頭孢菌素)從腦脊液向血液的主動轉運受阻,從而產生與腦組織藥物累積量相關的神經毒性[66,107]。

3.3 既往神經系統病史及其他病癥

已有多項研究表明既往神經系統病史是抗菌藥物神經毒性的重要危險因素之一。神經系統疾病如中風、腦血脈硬化、帕金森癥等都有潛在的加重抗菌藥物神經毒性作用;對于有癲癇史患者,使用抗菌藥物可能會降低癲癇發作閾值[108]。早期以及最近的研究表明,對于重癥肌無力患者,使用抗菌藥物會加重病癥[1,41,109]。一項評估以多黏菌素B為主治療革蘭陰性菌腦膜炎的有效性以及安全性的研究表明,有28%的患者在治療過程發生了神經毒性,原因可能在于細菌性腦膜炎能夠增加血腦屏障的通透性,使抗菌藥物易于滲透進入腦組織造成神經毒性[110-111]。除此之外,還有一些特殊病癥也會誘發或加重抗菌藥物的神經毒性,有研究表明原發性甲狀腺毒癥是環丙沙星致癲癇的潛在危險因素[112];膿毒癥與囊性纖維化癥也被認為具有潛在增加抗菌藥物神經毒性的作用,原因可能為這些病癥誘導的部分或全身炎癥導致血腦屏障通透性增加,從而增加抗菌藥物血腦屏障滲透率[35,113-114]。

3.4 聯合用藥

在使用抗菌藥物治療的時候,往往因為患者并發癥而聯合用藥,但不合理的聯合用藥可能會增加抗菌藥物發生神經毒性的風險。其誘發的機制可能為影響藥物代謝或共同作用增加其神經毒性。如氟喹諾酮類可抑制肝細胞色素(CYP450)酶活性,從而顯著降低茶堿肝清除率,使血中茶堿濃度明顯增高, 引起茶堿神經中毒癥狀[115];氟喹諾酮類與非類固醇類消炎鎮痛藥聯合用藥時還能協同增強氟喹諾酮類的抑制GABA作用從而誘發神經毒性[116-117]。同時還有研究表明多黏菌素與鎮靜劑、麻醉劑、皮質類固醇和肌肉松弛劑等藥物共同給藥時能提高多黏菌素發生神經毒性的風險[35]。

4 防治措施

4.1 嚴格把握適應癥以及給藥方案

對腎功能不全或腎衰竭、既往神經系統病史如癲癇、帕金森癥和精神病史等以及高齡患者應謹慎用藥,同時應當根據患者的機體代謝情況制定合理的給藥方案, 調整給藥劑量和用藥時間[118],例如在一項研究對比慶大霉素一次性給藥與分3次給藥造成耳毒性的研究中,結果表明一次性給藥方案相比分3次給藥不僅在治愈率上更具優勢(分別為87.5%和69.2%),在耳毒性風險方面也更為安全(一次性給藥方案0例,分3次給藥3例)[119];并且在出現神經毒性時應當及時停藥,同時根據用藥種類應避免藥物相互作用。

4.2 藥物控制神經毒性癥狀

有研究表明,在應對抗菌藥物尤其是碳青霉烯類藥物誘導的癲癇發作的治療中,苯二氮卓類被推薦為一線治療藥物,因其能通過增加氯離子通道開放的速率來增強GABAA的活性,從而導致神經元超極化,有效地控制由GABA拮抗引起的癲癇[120]。另外還能選取一些具有神經保護作用藥物如谷胱甘肽、神經節苷脂、雷帕霉素和紅景天苷等緩解抗菌藥物誘導的神經毒性[25,121]。

4.3 血藥濃度檢測(TDM)

對于治療指數窄,毒性作用強,個體差異大的抗菌藥物,應進行血藥濃度檢測,同時觀測患者在治療過程是否有癲癇發作、意識混亂、腦病以及痙攣等不良反應,結合患者病癥、血藥濃度以及生化指標制定更合理的給藥方案,為把控藥物的合理應用、建立個體化治療提供科學依據,如一項針對利奈唑胺個體精細化給藥的研究中,該文獻對TDM測定的利奈唑胺群體PK模型進行蒙特卡洛模擬,結果表明使用標準的給藥方案利奈唑胺(600 mg, q12h),對于MIC高于4 mg/L的菌株難以有效殺滅,對于這些菌株需要更高的藥物暴露量才能達到理想的臨床效果,但劑量增加可能導致超過30%的患者有潛在的神經毒副作用發生率,需考慮個體化給藥保證有效安全的藥物暴露[122]。

5 總結

神經毒性是抗菌藥物的一種常見且嚴重的毒副作用,其危險因素主要有腎衰竭、既往神經系統史、膿毒血癥、囊性纖維化、老齡患者以及藥物聯用。因此在治療前應充分了解患者既往病史及患者機體狀況,同時做好預防措施,如藥物濃度監測、腦電圖監測,結合患者生化指標提供合理的給藥方案,從而有效將患者血藥濃度控制在安全窗口內。神經毒性發生機制主要為呈濃度依賴性抑制或激活GABA、NMDA以及乙酰膽堿等神經遞質的傳遞,同時也有藥物能夠通過氧化應激誘導細胞凋亡導致神經毒性。對此,使用苯二氮卓類藥物以及神經保護劑在維持抗菌效果的同時減少抗菌藥物對神經系統的損傷也具有一定的前景。值得注意的是研究表明在神經系統感染、全身感染(膿毒癥)以及腎功能不全的患者中,血腦屏障受到炎癥因子的破壞導致滲透率增加,或者抑制腦-血轉運體都能增加神經毒性風險。因此進一步研究完善抗菌藥物的腦內轉運機制以及保護血腦屏障損傷也不失為減少抗菌藥物神經毒性不良反應的一個突破點。

參 考 文 獻

Rezaei N J, Bazzazi A M, Alavi S A N. Neurotoxicity of the antibiotics: A comprehensive study[J]. Neurol India, 2018, 66(6): 1732-1740.

Gschwind M, Simonetta F, Vulliemoz S. Reversible encephalopathy with photoparoxysmal response during imipenem/cilastatin treatment[J]. J Neurol Sci, 2016, 360: 23-24.

Grill M F, Maganti R K. Neurotoxic effects associated with antibiotic use: Management considerations[J]. Br J Clin Pharmacol, 2011, 72(3): 381-393.

Morales D, Pacurariu A, Slattery J, et al. Association between peripheral neuropathy and exposure to oral fluoroquinolone or amoxicillin-clavulanate therapy[J]. JAMA Neurol, 2019, 76(7): 827-833.

Goolsby T A, Jakeman B, Gaynes R P. Clinical relevance of metronidazole and peripheral neuropathy: A systematic review of the literature[J]. Int J Antimicrob Agents, 2018, 51(3): 319-325.

Leis J A, Rutka J A, Gold W L, et al. Aminoglycoside-induced ototoxicity[J]. CMAJ, 2015, 187(1): E52.

Bischoff A, Meier C, Roth F. Gentamicin neurotoxicity (polyneuropathy-encephalopathy)[J]. Schweiz Med Wochenschr, 1977, 107(1): 3-8.

Tange R A, Dreschler W A, Prins J M, et al. Ototoxicity and nephrotoxicity of gentamicin vs netilmicin in patients with serious infections: A randomized clinical trial[J]. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci, 1995, 20(2): 118-123.

Tulkens P M. Pharmacokinetic and toxicological evaluation of a once-daily regimen versus conventional schedules of netilmicin and amikacin[J]. J Antimicrob Chemother, 1991, 27(Suppl C): 49-61.

Klis S, Stienstra Y, Phillips R O, et al. Long term streptomycin toxicity in the treatment of Buruli Ulcer: follow-up of participants in the BURULICO drug trial[J]. PLoS Negl Trop Dis, 2014, 8(3): e2739.

Lerner A M, Reyes M P, Cone L A, et al. Randomised, controlled trial of the comparative efficacy, auditory toxicity, and nephrotoxicity of tobramycin and netilmicin[J]. Lancet, 1983, 1(8334): 1123-1126.

Bhattacharyya S, Berkowitz A L. Cephalosporin neurotoxicity: An overlooked cause of toxic-metabolic encephalopathy[J]. J Neurol Sci, 2019, 398: 194-195.

Triplett J D, Lawn N D, Chan J, et al. Cephalosporin-related neurotoxicity: Metabolic encephalopathy or non-convulsive status epilepticus?[J]. J Clin Neurosci, 2019, 67: 163-166.

Lin C S, Cheng C J, Chou C H, et al. Piperacillin/tazobactam-induced seizure rapidly reversed by high flux hemodialysis in a patient on peritoneal dialysis[J]. Am J Med Sci, 2007, 333(3): 181-184.

Huang W T, Hsu Y J, Chu P L, et al. Neurotoxicity associated with standard doses of piperacillin in an elderly patient with renal failure[J]. Infection, 2009, 37(4): 374-376.

Boschung-Pasquier L, Atkinson A, Kastner L K, et al. Cefepime neurotoxicity: Thresholds and risk factors. A retrospective cohort study[J]. Clin Microbiol Infect, 2020, 26(3): 333-339.

Grill M F, Maganti R. Cephalosporin-induced neurotoxicity: clinical manifestations, potential pathogenic mechanisms, and the role of electroencephalographic monitoring[J]. Ann Pharmacother, 2008, 42(12): 1843-1850.

Chow K M, Szeto C C, Hui A C, et al. Retrospective review of neurotoxicity induced by cefepime and ceftazidime[J]. Pharmacotherapy, 2003, 23(3): 369-373.

Quinton M C, Bodeau S, Kontar L, et al. Neurotoxic concentration of piperacillin during continuous infusion in critically III patients[J]. Antimicrob Agents Chemother, 2017, 61(9): e00654-17.

Olthof E, Tostmann A, Peters W H, et al. Hydrazine-induced liver toxicity is enhanced by glutathione depletion but is not mediated by oxidative stress in HepG2 cells[J]. Int J Antimicrob Agents, 2009, 34(4): 385-386.

Xiao C, Han Y, Liu Y, et al. Relationship between fluoroquinolone structure and neurotoxicity revealed by zebrafish neurobehavior[J]. Chem Res Toxicol, 2018, 31(4): 238-250.

Bhalerao S, Talsky A, Hansen K, et al. Ciprofloxacin-induced manic episode[J]. Psychosomatics, 2006, 47(6): 539-540.

Traeger S M, Bonfiglio M F, Wilson J A, et al. Seizures associated with ofloxacin therapy[J]. Clin Infect Dis, 1995, 21(6): 1504-1506.

Nishikubo M, Kanamori M, Nishioka H. Levofloxacin-associated neurotoxicity in a patient with a high concentration of levofloxacin in the blood and cerebrospinal fluid[J]. Antibiotics (Basel), 2019, 8(2): 78.

Dai C, Xiao X, Li J, et al. Molecular mechanisms of neurotoxicity induced by polymyxins and chemoprevention[J]. ACS Chem Neurosci, 2019, 10(1): 120-131.

Zhou Y, Li Y, Xie X, et al. Higher incidence of neurotoxicity and skin hyperpigmentation in renal transplant patients treated with polymyxin B[J]. Br J Clin Pharmacol, 2022, 88(11): 4742-4750 .

Kelesidis T, Falagas M E. The safety of polymyxin antibiotics[J]. Expert Opin Drug Saf, 2015, 14(11): 1687-1701.

Quickfall D, Daneman N, Dmytriw A A, et al. Metronidazole-induced neurotoxicity[J]. CMAJ, 2021, 193(42): E1630.

Kim E, Na D G, Kim E Y, et al. MR imaging of metronidazole-induced encephalopathy: Lesion distribution and diffusion-weighted imaging findings[J]. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol, 2007, 28(9): 1652-1658.

Saidinejad M, Ewald M B, Shannon M W. Transient psychosis in an immune-competent patient after oral trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole administration[J]. Pediatrics, 2005, 115(6): e739-741.

Gray D A, Foo D. Reversible myoclonus, asterixis, and tremor associated with high dose trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole: A case report[J]. J Spinal Cord Med, 2016, 39(1): 115-117.

Ikeda A K, Prince A A, Chen J X, et al. Macrolide-associated sensorineural hearing loss: A systematic review[J]. Laryngoscope, 2018, 128(1): 228-236.

Bandettini di Poggio M, Anfosso S, Audenino D, et al. Clarithromycin-induced neurotoxicity in adults[J]. J Clin Neurosci, 2011, 18(3): 313-318.

Clark D B, Andrus M R, Byrd D C. Drug interactions between linezolid and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors: case report involving sertraline and review of the literature[J]. Pharmacotherapy, 2006, 26(2): 269-276.

Wanleenuwat P, Suntharampillai N, Iwanowski P. Antibiotic-induced epileptic seizures: Mechanisms of action and clinical considerations[J]. Seizure, 2020, 81: 167-174.

Fu X, Wan P, Li P, et al. Mechanism and prevention of ototoxicity induced by aminoglycosides[J]. Front Cell Neurosci, 2021, 15: 692762.

Leung K. 4-Acetoxy-7-chloro-3-(3-(-4-[11C]methoxybenzyl)phenyl)-2(1H)-quinolone[M]. Molecular Imaging and Contrast Agent Database (MICAD). Bethesda (MD), 2009.

Wang J, Yi M, Chen X, et al. Effects of colistin on amino acid neurotransmitters and blood-brain barrier in the mouse brain[J]. Neurotoxicol Teratol, 2016, 55: 32-37.

Nar Z, Edizer D T, Yiit Z, et al. Does calcium dobesilate have therapeutic effect on gentamicin-induced cochlear nerve ototoxicity? An experimental study[J]. Otol Neurotol, 2020, 41(10): e1185-e1192.

Dai C, Tang S, Biao X, et al. Colistin induced peripheral neurotoxicity involves mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress in mice[J]. Mol Biol Rep, 2019, 46(2): 1963-1972.

Gummi R R, Kukulka N A, Deroche C B, et al. Factors associated with acute exacerbations of myasthenia gravis[J]. Muscle Nerve, 2019, 60(6): 693-699.

Sheikh S, Alvi U, Soliven B, et al. Drugs that induce or cause deterioration of myasthenia gravis: An update[J]. J Clin Med, 2021, 10(7): 1537.

Kuznetsov A V, Margreiter R, Amberger A, et al. Changes in mitochondrial redox state, membrane potential and calcium precede mitochondrial dysfunction in doxorubicin-induced cell death[J]. Biochim Biophys Acta, 2011, 1813(6): 1144-1152.

Rizzi M D, Hirose K. Aminoglycoside ototoxicity[J]. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg, 2007, 15(5): 352-357.

Van Hecke R, Van Rompaey V, Wuyts F L, et al. Systemic aminoglycosides-induced vestibulotoxicity in humans[J]. Ear Hear, 2017, 38(6): 653-662.

Steyger P S, Peters S L, Rehling J, et al. Uptake of gentamicin by bullfrog saccular hair cells in vitro[J]. J Assoc Res Otolaryngol, 2003, 4(4): 565-578.

Marcotti W, van Netten S M, Kros C J. The aminoglycoside antibiotic dihydrostreptomycin rapidly enters mouse outer hair cells through the mechano-electrical transducer channels[J]. J Physiol, 2005, 567(Pt 2): 505-521.

Waguespack J R, Ricci A J. Aminoglycoside ototoxicity: Permeant drugs cause permanent hair cell loss[J]. J Physiol, 2005, 567(Pt2): 359-360.

Warchol M E. Cellular mechanisms of aminoglycoside ototoxicity[J]. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg, 2010, 18(5): 454-458.

Steyger P S. Mechanisms of aminoglycoside- and cisplatin-induced ototoxicity[J]. Am J Audiol, 2021, 30(3S): 887-900.

Hobbie S N, Akshay S, Kalapala S K, et al. Genetic analysis of interactions with eukaryotic rRNA identify the mitoribosome as target in aminoglycoside ototoxicity[J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2008, 105(52): 20888-20893.

Guan M X. Mitochondrial 12S rRNA mutations associated with aminoglycoside ototoxicity[J]. Mitochondrion, 2011, 11(2): 237-245.

Kros C J, Steyger P S. Aminoglycoside- and cisplatin-induced ototoxicity: Mechanisms and otoprotective strategies[J]. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med, 2019, 9(11): a033548.

Zareifopoulos N, Panayiotakopoulos G. Neuropsychiatric effects of antimicrobial agents[J]. Clin Drug Investig, 2017, 37(5): 423-437.

Shi L J, Liu L A, Cheng X H, et al. Decrease in acetylcholine-induced current by neomycin in PC12 cells[J]. Arch Biochem Biophys, 2002, 403(1): 35-40.

Krenn M, Grisold A, Wohlfarth P, et al. Pathomechanisms and clinical implications of myasthenic syndromes exacerbated and induced by medical treatments[J]. Front Mol Neurosci, 2020, 13: 156.

Liu C, Hu F. Investigation on the mechanism of exacerbation of myasthenia gravis by aminoglycoside antibiotics in mouse model[J]. J Huazhong Univ Sci Technolog Med Sci, 2005, 25(3): 294-296.

Lacroix C, Kheloufi F, Montastruc F, et al. Serious central nervous system side effects of cephalosporins: A national analysis of serious reports registered in the French Pharmacovigilance Database[J]. J Neurol Sci, 2019, 398: 196-201.

Tamune H, Hamamoto Y, Aso N, et al. Cefepime-induced encephalopathy: Neural mass modeling of triphasic wave-like generalized periodic discharges with a high negative component (Tri-HNC)[J]. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci, 2019, 73(1): 34-42.

Cock H R. Drug-induced status epilepticus[J]. Epilepsy Behav, 2015, 49: 76-82.

Sugimoto M, Uchida I, Mashimo T, et al. Evidence for the involvement of GABA(A) receptor blockade in convulsions induced by cephalosporins[J]. Neuropharmacology, 2003, 45(3): 304-314.

Sugimoto M, Fukami S, Kayakiri H, et al. The beta-lactam antibiotics, penicillin-G and cefoselis have different mechanisms and sites of action at GABA(A) receptors[J]. Br J Pharmacol, 2002, 135(2): 427-432.

Alkharfy K M, Kellum J A, Frye R F, et al. Effect of ceftazidime on systemic cytokine concentrations in rats[J]. Antimicrob Agents Chemother, 2000, 44(11): 3217-3219.

Block M L, Zecca L, Hong J S. Microglia-mediated neurotoxicity: Uncovering the molecular mechanisms[J]. Nat Rev Neurosci, 2007, 8(1): 57-69.

Preston R A, Mamikonyan G, Mastim M, et al. Single-center investigation of the pharmacokinetics of WCK 4282 (Cefepime-Tazobactam Combination) in renal impairment[J]. Antimicrob Agents Chemother, 2019,63(10): e00873-19.

Ohtaki K, Matsubara K, Fujimaru S, et al. Cefoselis, a beta-lactam antibiotic, easily penetrates the blood-brain barrier and causes seizure independently by glutamate release[J]. J Neural Transm (Vienna), 2004, 111(12): 1523-1535.

Lau A, Tymianski M. Glutamate receptors, neurotoxicity and neurodegeneration[J]. Pflugers Arch, 2010, 460(2): 525-542.

Mahmoud S, Gharagozloo M, Simard C, et al. Astrocytes maintain glutamate homeostasis in the CNS by controlling the balance between glutamate uptake and release[J]. Cells, 2019, 8(2): 184.

Rossokhin A V, Sharonova I N, Bukanova J V, et al. Block of GABA(A) receptor ion channel by penicillin: electrophysiological and modeling insights toward the mechanism[J]. Mol Cell Neurosci, 2014, 63: 72-82.

Shiraishi H, Ito M, Go T, et al. High doses of penicillin decreases [3H]flunitrazepam binding sites in rat neuron primary culture[J]. Brain Dev, 1993, 15(5): 356-361.

Ayd?n A, Bar?? Aykan M, Sa?lam K, et al. Seizure induced by ertapenem in an elderly patient with dementia[J]. Consult Pharm, 2017, 32(10): 561-562.

Sunagawa M, Matsumura H, Sumita Y, et al. Structural features resulting in convulsive activity of carbapenem compounds: effect of C-2 side chain[J]. J Antibiot (Tokyo), 1995, 48(5): 408-416.

Zivanovic D, Lovic O S, Susic V. Effects of manipulation of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors on imipenem/cilastatin-induced seizures in rats[J]. Indian J Med Res, 2004, 119(2): 79-85.

Koppel B S, Hauser W A, Politis C, et al. Seizures in the critically ill: The role of imipenem[J]. Epilepsia, 2001, 42(12): 1590-1593.

Ali A K. Peripheral neuropathy and Guillain-Barré syndrome risks associated with exposure to systemic fluoroquinolones: A pharmacovigilance analysis[J]. Ann Epidemiol, 2014, 24(4): 279-285.

Bhattacharyya S, Darby R R, Raibagkar P, et al. Antibiotic-associated encephalopathy[J]. Neurology, 2016, 86(10): 963-971.

Schwartz M T, Calvert J F. Potential neurologic toxicity related to ciprofloxacin[J]. DICP, 1990, 24(2): 138-140.

Kaur K, Fayad R, Saxena A, et al. Fluoroquinolone-related neuropsychiatric and mitochondrial toxicity. A collaborative investigation by scientists and members of a social network[J]. J Community Support Oncol, 2016, 14(2): 54-65.

De Sarro A, De Sarro G. Adverse reactions to fluoroquinolones. An overview on mechanistic aspects[J]. Curr Med Chem, 2001, 8(4): 371-384.

高偉波, 朱繼紅. 氟喹諾酮類藥物中樞神經系統不良反應及其防治[J]. 疑難病雜志, 2008, 7(8): 507-509.

Koch-Weser J, Sidel V W, Federman E B, et al. Adverse effects of sodium colistimethate. Manifestations and specific reaction rates during 317 courses of therapy[J]. Ann Intern Med, 1970, 72(6): 857-868.

Molina J, Cordero E, Pachón J. New information about the polymyxin/colistin class of antibiotics[J]. Expert Opin Pharmacother, 2009, 10(17): 2811-2828.

Dai C, Tang S, Velkov T, et al. Colistin-induced apoptosis of neuroblastoma-2a cells involves the generation of reactive oxygen species, mitochondrial dysfunction, and autophagy[J]. Mol Neurobiol, 2016, 53(7): 4685-700.

Ajiboye T O. Colistin sulphate induced neurotoxicity: Studies on cholinergic, monoaminergic, purinergic and oxidative stress biomarkers[J]. Biomed Pharmacother, 2018, 103: 1701-1707.

Yachan N, Yanqi C, You W, et al. Case report: Respiratory paralysis associated with polymyxin B therapy[J]. Front? ?Pharmacol, 2022, 13: 963140.

Lefkowitz A, Shadowitz S. Reversible cerebellar neurotoxicity induced by metronidazole[J]. CMAJ, 2018, 190(32): E961.

Hassan M H, Awadalla E A, Ali R A, et al. Thiamine deficiency and oxidative stress induced by prolonged metronidazole therapy can explain its side effects of neurotoxicity and infertility in experimental animals: Effect of grapefruit co-therapy[J]. Hum Exp Toxicol, 2020, 39(6): 834-847.

Lee K Y, Huang C H, Tang H J, et al. Acute psychosis related to use of trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole in the treatment of HIV-infected patients with Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia: A multicentre, retrospective study[J]. J Antimicrob Chemother, 2012, 67(11): 2749-2754.

Patey O, Lacheheb A, Dellion S, et al. A rare case of cotrimoxazole-induced eosinophilic aseptic meningitis in an HIV-infected patient[J]. Scand J Infect Dis, 1998, 30(5): 530-531.

Haruki H, Pedersen M G, Gorska K I, et al. Tetrahydrobiopterin biosynthesis as an off-target of sulfa drugs[J]. Science, 2013, 340(6135): 987-991.

Principi N, Esposito S. Comparative tolerability of erythromycin and newer macrolide antibacterials in paediatric patients[J]. Drug Saf, 1999, 20(1): 25-41.

Li J, Min Z, Li W, et al. Interactive effects of roxithromycin and freshwater microalgae, Chlorella pyrenoidosa: Toxicity and removal mechanism[J]. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf, 2020, 191: 110156.

Yorgason J G, Luxford W, Kalinec F. In vitro and in vivo models of drug ototoxicity: Studying the mechanisms of a clinical problem[J]. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol, 2011, 7(12): 1521-1534.

Narita M, Tsuji B T, Yu V L. Linezolid-associated peripheral and optic neuropathy, lactic acidosis, and serotonin syndrome[J]. Pharmacotherapy, 2007, 27(8):1189-1197.

Flanagan S, McKee E E, Das D, et al. Nonclinical and pharmacokinetic assessments to evaluate the potential of tedizolid and linezolid to affect mitochondrial function[J]. Antimicrob Agents Chemother, 2015, 59(1): 178-185.

Cunha B A. Antibiotic side effects[J]. Med Clin North Am, 2001, 85(1): 149-185.

Kumar A, Roberts D, Wood K E, et al. Duration of hypotension before initiation of effective antimicrobial therapy is the critical determinant of survival in human septic shock[J]. Crit Care Med, 2006, 34(6): 1589-1596.

Jafarinasabian P, Inglis J E, Reilly W, et al. Aging human body: Changes in bone, muscle and body fat with consequent changes in nutrient intake[J]. J Endocrinol, 2017, 234(1): R37-R51.

李輝, 芮建中. 慢性腎衰竭對非腎消除藥物體內代謝與轉運的影響[J]. 中國臨床藥理學雜志, 2017, 33(21): 2179-2181.

Dro?dzik M, Oswald S, Dro?dzik A. Impact of kidney dysfunction on hepatic and intestinal drug transporters[J]. Biomed Pharmacother, 2021, 143: 112125.

Torres A M, Dnyanmote A V, Granados J C, et al. Renal and non-renal response of ABC and SLC transporters in chronic kidney disease[J]. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol, 2021, 17(5): 515-542.

Hamed S A. Neurologic conditions and disorders of uremic syndrome of chronic kidney disease: Presentations, causes, and treatment strategies[J]. Exp Rev Clin Pharmacol, 2019, 12(1): 61-90.

Mattappalil A, Mergenhagen K A. Neurotoxicity with antimicrobials in the elderly: A review[J]. Clin Ther, 2014, 36(11): 1489-1511.e4.

Freeman R B, Sheff M F, Maher J F, et al. The blood-cerebrospinal fluid barrier in uremia[J]. Ann Intern Med, 1962, 56: 233-240.

Deguchi T, Isozaki K, Yousuke K, et al. Involvement of organic anion transporters in the efflux of uremic toxins across the blood-brain barrier[J]. J Neurochem, 2006, 96(4): 1051-1059.

Kahan F M, Kropp H, Sundelof J G, et al. Thienamycin: Development of imipenen-cilastatin[J]. J Antimicrob Chemother, 1983, 12(Suppl D): 1-35.

Chow K M, Szeto C C, Hui A C, et al. Mechanisms of antibiotic neurotoxicity in renal failure[J]. Int J Antimicrob Agents, 2004, 23(3): 213-217.

Czapińska-Ciepiela E. The risk of epileptic seizures during antibiotic therapy[J]. Wiad Lek, 2017, 70(4): 820-826.

Hokkanen E. The aggravating effect of some antibiotics on the neuromuscular blockade in myasthenia gravis[J]. Acta Neurol Scand, 1964, 40(4): 346-352.

Falagas M E, Bliziotis I A, Tam V H. Intraventricular or intrathecal use of polymyxins in patients with Gram-negative meningitis: A systematic review of the available evidence[J]. Int J Antimicrob Agents, 2007, 29(1): 9-25.

Yau B, Hunt N H, Mitchell A J, et al. Blood-brain barrier pathology and CNS Outcomes in Streptococcus pneumoniae Meningitis[J]. Int J Mol Sci, 2018, 19(11): 3555.

Agbaht K, Bitik B, Piskinpasa S, et al. Ciprofloxacin-associated seizures in a patient with underlying thyrotoxicosis: case report and literature review[J]. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther, 2009, 47(5): 303-310.

Rekis N, Ambrose M, Sakon C. Neurotoxicity in adult patients with cystic fibrosis using polymyxin B for acute pulmonary exacerbations[J]. Pediatr Pulmonol, 2020, 55(5): 1094-1096.

Jin L, Li J, Nation R L, et al. Impact of p-glycoprotein inhibition and lipopolysaccharide administration on blood-brain barrier transport of colistin in mice[J]. Antimicrob Agents Chemother, 2011, 55(2): 502-507.

周義文. 抗感染藥物對神經系統的毒性作用[J]. 中國實用內科雜志, 2001, 21(11): 692-694.

Giardina W J. Assessment of temafloxacin neurotoxicity in rodents[J]. Am J Med, 1991, 91(6A): 42S-44S.

Motomura M, Kataoka Y, Takeo G, et al. Hippocampus and frontal cortex are the potential mediatory sites for convulsions induced by new quinolones and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs[J]. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther Toxicol, 1991, 29(6): 223-227.

Hoff B M, Maker J H, Dager W E, et al. Antibiotic dosing for critically ill adult patients receiving intermittent hemodialysis, prolonged intermittent renal replacement therapy, and continuous renal replacement therapy: An update[J]. Ann Pharmacother, 2020, 54(1): 43-55.

Raz R, Adawi M, Romano S. Intravenous administration of gentamicin once daily versus thrice daily in adults[J]. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis, 1995, 14(2): 88-91.

Payne L E, Gagnon D J, Riker R R, et al. Cefepime-induced neurotoxicity: A systematic review[J]. Crit Care, 2017, 21(1): 276.

郭昌, 趙文韜, 胡豐良. 奧沙利鉑神經毒性的機制及防治研究進展[J]. 現代中西醫結合雜志, 2020, 29(9): 1022-1026.

Luque S, Hope W, Sorli L, et al. Dosage individualization of linezolid: precision dosing of linezolid to optimize efficacy and minimize toxicity[J]. Antimicrob Agents Chemother, 2021, 65(6): e02490-20.