Delayed post-hypoxic leukoencephalopathy following barbiturate overdose: A case report

Arshi Syal, Samiksha Gupta, Monica Gupta, Gautam Jesrani, Yajur Arya

Department of General Medicine, Government Medical College and Hospital, Chandigarh, India

ABSTRACT Rationale: Delayed post-hypoxic leukoencephalopathy (DPHL) is usually an overlooked condition, which arises as a result of a multitude of reversible and irreversible conditions.Patient’s Concern: A 50-year-old female with a history of epilepsy, who developed DPHL 12 days after respiratory failure secondary to barbiturate toxicity.Diagnosis: DPHL on magnetic resonance imaging of the brain.Interventions: Mechanical ventilation was initiated for respiratory failure and hemodialysis for barbiturate toxicity.Outcomes: The patient developed akinetic mutism due to infirmity and had a residual disability, which led to permanent dependency.Lessons: The diagnosis of DPHL is often delayed or missed, given the rarity of this condition and its inconsistent clinical symptomatology. Diagnostic delay can be avoided by early recognition of the classical “delayed onset” symptoms.

KEYWORDS: Delayed post-hypoxic leukoencephalopathy; Barbiturate overdose; Epilepsy; Respiratory failure; Akinetic mutism

1. Introduction

Delayed post-hypoxic leukoencephalopathy (DPHL) is a rare clinical entity characterized by neuropsychiatric sequelae that occur following recovery from an initial cerebral insult. This biphasic illness is characterized by a period of improvement following an acutely altered neurological status, later followed by a recurrence of neurologic deterioration. This neurological deterioration typically resurfaces after a latent period of approximately one to two weeks, and it can extend up to 40 days after the inciting event[1]. Literature yields reports of DPHL secondary to carbon monoxide poisoning and infrequently due to rarer causes including drug overdose (opioids, benzodiazepines, barbiturates, and alcohol, with approximately 5 cases reported caused by benzodiazepine overdose)[2].

2. Case report

After explaining thoroughly that the case information will be used for education purposes only, written patient consent was present and was obtained on all appropriate forms from the patient’s husband. The husband understood that her names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

A 50-year-old female with previously diagnosed epilepsy was brought to the emergency room with a sudden onset of loss of consciousness. The patient had altered sensorium for one day before the episode. It was not associated with fever, headache, vomiting, or convulsions before or after the episode or trauma. She was diagnosed with epilepsy and was on barbiturates for the past 10 years. On evaluation, she was afebrile with a regular pulse rate of 80/minute (range: 60-100/min), blood pressure of 90/60 mmHg (range: systolic 90-120 mmHg, diastolic 60-80 mmHg), respiratory rate of 10/minute (range: 12-16/min) with a regular and shallow breathing pattern along with an oxygen saturation of 70% (range: 95%-100%) under room air. She had a Glasgow Coma Scale of 9/15. Bilaterally the pupils were miotic, approximately 1 mm in size. A thorough neurological examination ruled out any focal neurological deficits. Fundus was normal without evidence of disc edema. The rest of the systemic examination was unremarkable. Her random blood glucose level was 112 mg/dL (range: 70-199 mg/dL). Arterial blood gas analysis at the time of admission revealed lactic acidosis. Electrocardiogram and chest radiograph were unremarkable. An electroencephalogram did not show any evidence of epileptic activity.

A detailed laboratory workup was performed. Her complete blood count was unremarkable apart from an elevated total leukocyte count. Her C-reactive protein, liver and renal function tests, and serum electrolytes were within normal limits. Thyroid function tests, lipid profile, and glycated hemoglobin were normal. Hepatitis B surface antigen and serologies for human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis C, and Venereal Disease Research Laboratory test were negative. Cerebrospinal fluid analysis was unremarkable but urinalysis was positive for barbiturates. An autoimmune and metabolic panel did not direct towards any specific etiology.

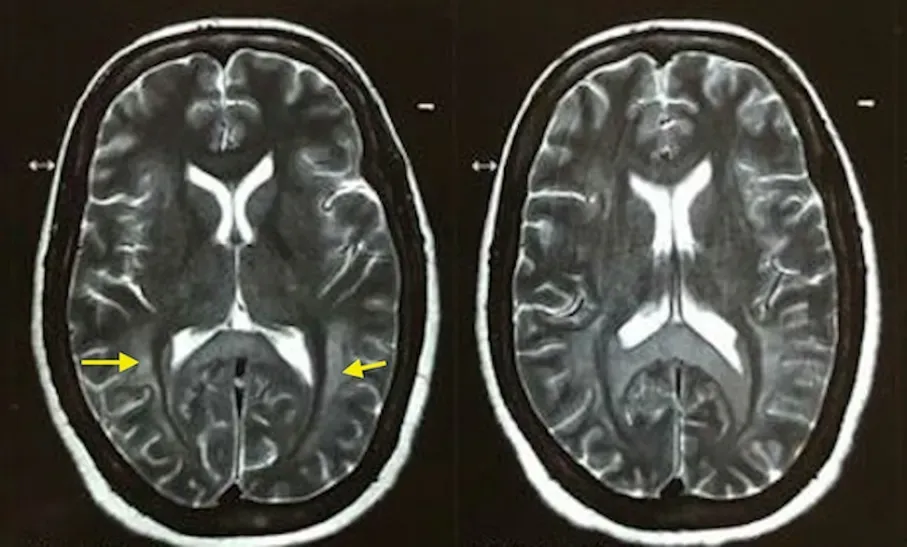

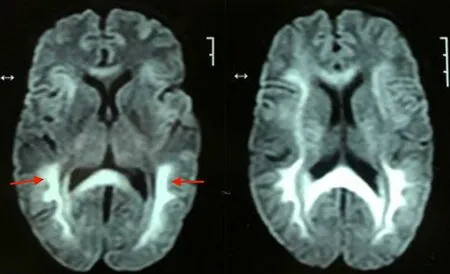

A diagnosis of respiratory failure secondary to barbiturate toxicity was made after excluding alternative possibilities. The patient was initially managed symptomatically with endotracheal intubation and mechanical ventilation for respiratory failure. The patient underwent one cycle of hemodialysis due to barbiturate toxicity. She showed considerable improvement in mental status and spontaneous respiratory drive over the next two days. However, 12 days after the inciting event, she developed akinetic mutism. A contrastenhanced magnetic resonance imaging of the brain (CEMRI-Brain) was subsequently performed and revealed symmetric and diffuse fluid-attenuated inversion recovery and increased signal intensity involving the subcortical, deep, and periventricular white matter in the frontoparietal-occipital lobes bilaterally (Figure 1). Diffusion restriction was observed on diffusion-weighted imaging for the same cerebral regions (Figure 2). A diagnosis of DPHL was therefore made based on the characteristic imaging findings. Throughout her hospital course, there was negligible recovery thereafter. She was ultimately tracheostomised and eventually discharged for homebased nursing care.

Figure 1. The MRI brain image of a 50-year-old female. Symmetric diffuse in T2-weighted contrast-enhanced MRI of the brain (yellow arrow heads) involving the subcortical, deep and periventricular white matter in the frontoparietal-occipital lobes in bilateral cerebral hemispheres with sparing of subcortical “U” fibers.

Figure 2. The MRI brain image of a 50-year-old female. Diffusion restriction in the subcortical, deep and periventricular white matter in the frontoparietaloccipital lobes (red arrow heads) in bilateral cerebral hemispheresis seen on diffusion-weighted images.

3. Discussion

The spectrum of clinical presentation of DPHL is diverse. The entity is often characterized by two forms of clinical manifestation, an akinetic-mute form, as described in our case which is seen as a change in behavior, flawed actions, and psychomotor deterioration which progresses to mutism. The other form presents as a Parkinson-like syndrome. A rare instance of Kluver Bucy Syndrome accompanying DPHL has also been reported[3].

Although the exact pathophysiology has not been delineated, distinct mechanisms have been postulated for development of this selective white matter injury. Wallerian degeneration, adenosine triphosphate depletion, lipid peroxidation, inflammatory reaction, microglial proliferation, and delayed apoptosis of oligodendrocytes have been implicated[4]. Myelin-sheath damage is also postulated, which might be caused by protraction of oxygen reduction. Since myelin secretion occurs every 19 to 22 days, it shows a relationship with the postponed occurrence of symptoms after a latent period of 2-40 days (23 days on average)[5]. Recent reports have implicated the involvement of ascending reticular activating system in its pathophysiology, chiefly contributing to altered consciousness in these patients[6]. MRI brain is the modality of choice to diagnose DPHL. The T2-weighted hyperintense lesions of the white matter are classically homogeneously distributed and tend to occur symmetrically involving both the hemispheres as seen in our patient. The cortex and U-fibers, cerebellum, and brain stem are usually uninvolved[7].

Delayed white matter reversal on diffusion-weighted imaging, with white matter having a higher diffusion restriction than grey matter only develops gradually after a lag period and is diagnostic of DPHL[8]. The extension of diffusion restriction beyond the white matter to the cortical rim favors other aetiologies like generalized cerebral edema secondary to global hypoxia, carbon monoxide poisoning, as well as posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome[9].

Supportive therapy forms the cornerstone of management. Previous reviews have documented a favorable outcome with use of certain medications including magnesium sulfate, amantadine, and certain second-generation antipsychotics[10]. Rationale for the use of magnesium sulfate is two-pronged, firstly the use of intravenous magnesium sulfate can lead to resolution of akinetic mutism associated with DPHL in the acute phase. Secondarily, it may halt the progression as well as improve the neuropsychiatric and extrapyramidal symptoms cardinal to DPHL. Therefore, it is a promising treatment modality for acutely managing the distressing symptoms associated with this rare clinical entity[10]. Involvement of the deep grey matter on the other hand is associated with adverse clinical outcomes. Overall, the prognosis is favorable, and a majority show substantial recovery, however, persistent deficits in the frontalexecutive region are common.

4. Conclusion

This infrequently occurring clinical syndrome usually arises three to four weeks after the initial hypoxic brain insult. Clinical presentation can have marked variations and differences from one case to another. While most cases tend to show recovery, debilitating sequelae can occur and deficits can persist for significant durations as seen in our patient. The key to diagnosis is early anticipation and recognition of post-hypoxic leukoencephalopathy. Various treatment modalities have been used in successful management of selected cases, although clinical trials are needed to establish their efficacy.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors report no conflict of interest.

Funding

This study received no extramural funding.

Authors’ contributions

A.S. provided the concept and design of the study and contributed to data acquisition, analysis and interpretation, review of literature, and preparation of the first draft. S.G. contributed to data acquisition, analysis, and interpretation, review of literature, and modification of the draft. M.G. contributed to critical comments, data analysis, and interpretation, review of literature, and modification of the draft for final publication. G.J. contributed to data analysis, review of literature, and modification of the draft. Y.A. contributed to data analysis and interpretation, review of literature, and modification of the draft for final publication.

Journal of Acute Disease2022年4期

Journal of Acute Disease2022年4期

- Journal of Acute Disease的其它文章

- Challenges of COVID-19 prevention and control: A narrative review

- Severe progression of autoimmune hepatitis in a young COVID-19 adult patient: A case report

- Associated risk factors for post-COVID-19 mucormycosis at a tertiary care centre: A cross-sectional study

- Hematological indices as predictors of mortality in dengue shock syndrome: A retrospective study

- Different routine laboratory tests in assessment of COVID-19: A casecontrol study

- Effect of oral premedication of midazolam, ketamine, and dexmedetomidine on pediatric sedation and ease of parental separation in anesthesia induction for elective surgery: A randomized clinical trial