Comprehensive performance of a ball-milled La0.5Pr0.5Fe11.4Si1.6B0.2Hy/Al magnetocaloric composite

Jiao-Hong Huang(黃焦宏) Ying-De Zhang(張英德) Nai-Kun Sun(孫乃坤) Yang Zhang(張揚)Xin-Guo Zhao(趙新國) and Zhi-Dong Zhang(張志東)

1State Key Laboratory of Baiyunobo Rare Earth Resource Researches and Comprehensive Utilization,Baotou Research Institute of Rare Earths,Baotou 014030,China

2School of Science,Shenyang Ligong University,Shenyang 110159,China

3Shenyang National Laboratory for Materials Science,Institute of Metal Research,Chinese Academy of Sciences,Shenyang 110016,China

Keywords: ball milling,mechanical behavior,room-temperature magnetic refrigeration,La(Fe,Si)13

1. Introduction

La(Fe,Si)13-based hydrides have demonstrated a great potential for applications in room-temperature magnetic refrigeration by virtue of their large magnetic entropy change, abundant constituent elements and cascading of magnetic transition temperature across the near room-temperature range by Mn substitution or adjustment of the hydrogen content.[1,2]However, due to the hydrogen embrittlement effect, La(Fe,Si)13-based hydrides can only exist in powder form, which poses a challenge for shaping these materials into bulk magnetocaloric refrigerants for various regenerator configurations.Recently, a metal-bonding approach was employed for bulk formation of La(Fe,Si)13hydrides and this had the simultaneous effect of enhancing the mechanical and thermal conduction properties.[3-5]Compared with other metal bonders,such as Cu,Bi,In and Sn,metal Al possesses a better comprehensive performance with a unique combination of strength and corrosion resistance,non-toxicity and low cost,and high ductility and thermal conductivity.[6]In first-order transition of giant magnetocaloric materials, substitution or addition of B could reduce the lattice volume discontinuities at the transition temperature, thereby reducing the hysteresis loss[7]and improving mechanical stability.[8]

In our previous works,[9,10]a series of La(Fe,Si)13bulk hydrides were prepared by sintering under high hydrogen pressure. Unfavorably, in these sintered hydrides, a large number of micropores were distributed in the main phase matrix,substantially reducing the compressive strength and thermal conductivity. Considering these aforementioned factors,in this work we employ metal Al as a bonder to produce La0.5Pr0.5Fe11.4Si1.6B0.2Hy/Al bulk composites. Hydrogenation and compactness shaping of the magnetocaloric composites were fulfilled in one step via a high-pressure sintering process. The comprehensive performance associated with application in magnetic refrigeration was systematically explored.

2. Experiment

The parent compounds of LaFe11.4Si1.56and La0.5Pr0.5Fe11.4Si1.6B0.2were prepared by melting starting materials with purity of≥99.9 wt.% using a mediumfrequency induction furnace, as described in detail in Ref. [11]. The ball milling method was employed to homogeneously mix the La(Fe,Si)13-based compounds with metal Al according to weight ratios of 60:1, 10:1, and 5:1; the resultant composites are referred to as 1.6 wt.% Al, 9 wt.%Al, and 16.7% wt.% Al samples, respectively. The materials were sealed in a hardened steel vial in a high-purity argon atmosphere and then ball milled for 30 min. The ball-milled powders were cold-pressed into thin plates (12.6-mm diameter, 1-mm thick) and sintered for 10 min at 290°C in a high-pressure H2atmosphere of 50 MPa for hydrogenation and compaction. Subsequent annealing was conducted at 200°C for 2 h to reduce interface defects.Importantly,a highpressure atmosphere was retained during the whole annealing and cooling process to suppress hydrogen desorption.

X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis was carried out using Cu-Kαradiation in a Rigaku D/Max-γA diffractometer. The microstructure and elemental composition of the composites were characterized by means of a FEI Quanta 200 F scanning electron microscope (SEM) equipped with an energydispersed x-ray(EDX)spectrometer. The compressive strainstress curve was measured with a universal testing machine.The magnetic properties were measured with a superconducting quantum interference device magnetometer using the reciprocating sample option as the measurement mode. The adiabatic temperature changes ΔTadwere directly measured using a self-made setup.[11]A laser flash thermal conductivity apparatus(LFA 457)was employed for measuring the thermal conductivityλalong the vertical direction of the sintered thin plates by directly measuring the thermal diffusivity,D,and indirectly deriving the specific capacityCpusing a representative Cu sample.

3. Results and discussion

For a good compactness effect, with the premise of ensuring stability of the 1:13 main phase, the sintering temperature should be as high as possible. To explore the optimum sintering temperature, we first sintered the ballmilled LaFe11.4Si1.56/Al composite at 500°C for 2 h. The XRD pattern shows a strong combined reflection peak of the Fe3Al0.5Si0.5phase andα-Fe at~45°and an intermetallic phase, Fe2Al5, is also formed. Notably, upon hydrogenation the reflections of the cubic NaZn13-type structure unexpectedly shift to higher angles, indicating substantial decomposition of the 1:13 main phase (Fig. 1(a)). After checking the phase constitutions of the sintered composites, the optimum sintering temperature and time were determined to be 290°C and 10 min,respectively.Selected XRD patterns of asprepared La0.5Pr0.5Fe11.4Si1.6B0.2Hy/Al composites are shown in Fig. 1(b). For the 1.6 wt.% Al sample, the reflection peak of pure Al is not detected,and with increase in the Al content to 9 wt.%and 16.7 wt.%,an apparent reflection peak of pure Al is observed. Small reflection peaks were identified to correspond toθ-Al2O3and FeAl9Si3, indicating that Al is easy to oxidize in the ball milling process.

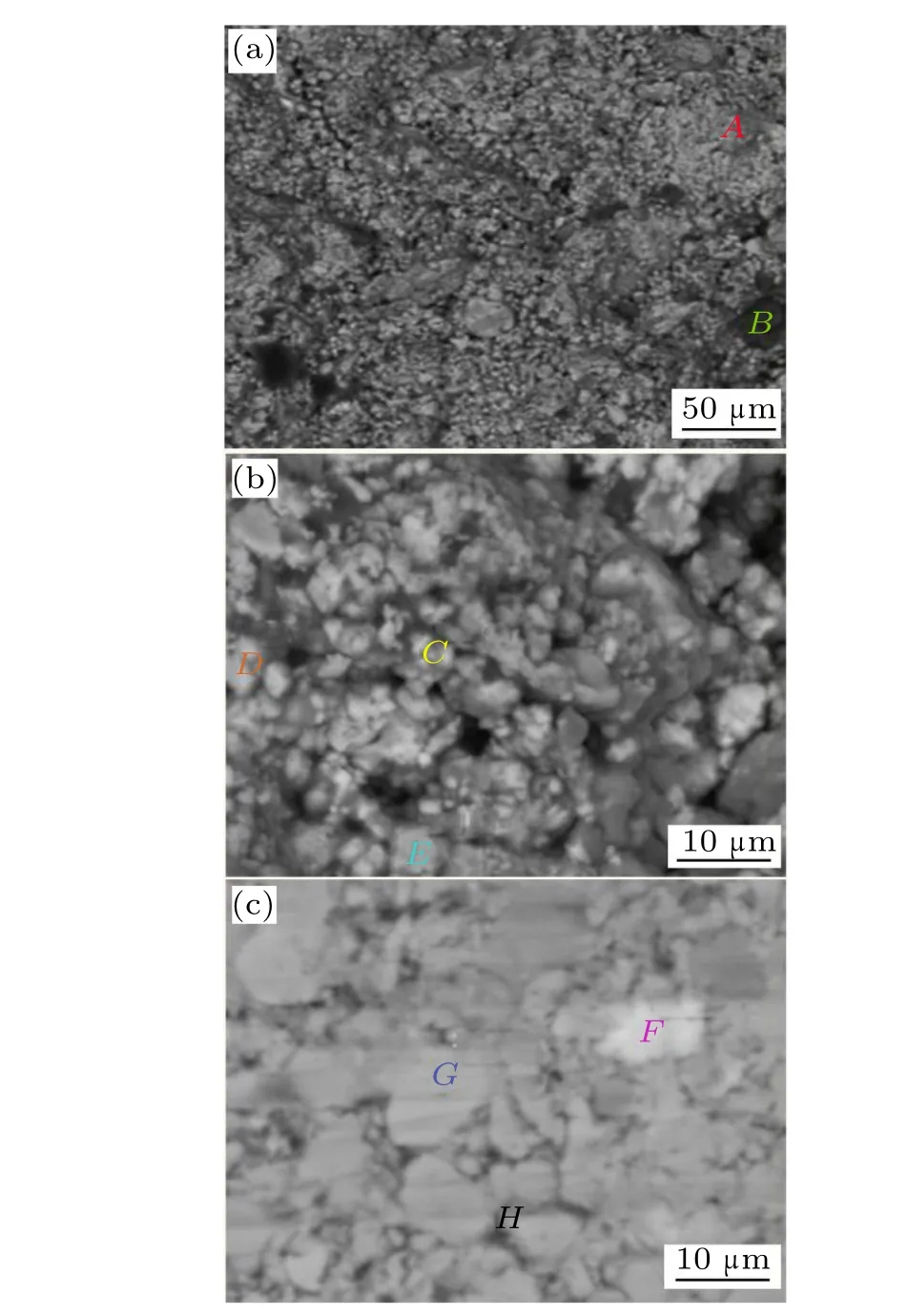

Figures 2(a)-2(c)illustrate the fracture and surface morphology of the 9 wt.%Al sample. An EDX study was carried out in eight typical areasA-Hfor analyzing the Al distribution and phase compositions. The grey areaAon the fracture surface has a small concentration of Al (2.5 at.%) and a predominant concentration of the 1:13 main phase. The elemental compositions in the dark areaBare mostly Al (28 at.%)and O(71 at.%)with small concentration of Fe(0.6 at.%)and Si (0.2 at.%), indicating that this kind of grey area predominantly consists of Al2O3. AreaC, corresponding to a single large La0.5Pr0.5Fe11.4Si1.6B0.2Hyparticle, has the smallest Al concentration of 1.5 at.% and areasDandEcontain an Al concentration of 10 at.%-15 at.%. The surface morphology in Fig. 2(c) clearly shows three typical areas, a white areaF, a grey areaGand a dark grey areaH. The Al concentrations for areasFandGare 15 at.% and 1 at.%, respectively. AreaHcontains 41 at.%O and 13 at.%Al,indicating that this kind of dark grey area on the surface is mainly composed of Al2O3.

Fig.1. Selected XRD patterns of(a)LaFe11.4Si1.56 and LaFe11.4Si1.56Hy/Al(4 wt.%)composite and(b)La0.5Pr0.5Fe11.4Si1.6B0.2Hy/Al composites.

From the expanded view of fracture morphology(Fig.2(b))and surface morphology(Fig.2(c)),we can clearly observe that the particles have a large size distribution ranging from submicron to~10 microns with a predominant number of particles having sizes of several microns; this can be ascribed to the ball milling process. In contrast, La(Fe,Si)13-based bulk hydrides prepared by other methods generally have much larger particle sizes of tens of microns.[12,13]Together,the results of XRD and EDX analyses indicate that upon ball milling, aluminum oxides fill up the gaps and pure Al, Fe-Al-Si alloys andα-Fe are distributed in the 1:13 main phase particles;these cannot be individually identified.

Fig.2. SEM images of(a)and(b)fracture morphology and(c)surface morphology of La0.5Pr0.5Fe11.4Hy/Al(9 wt.%).

The distribution of ductile Al bonder in the 1:13 phase matrix as well as the fact that the gaps are filled up with Al2O3should remarkably enhance the mechanical and thermal conduction properties. As shown in Fig. 3, the compressive strength of 42 MPa for the 1.6 wt.% Al-bonded composite is in a similar range of magnitude to the sintered(36 MPa-46 MPa)[9]and epoxy-resin-bonded La(Fe,Si)13hydrides (52 MPa).[13]Moreover, these bulk hydrides prepared by different methods all show a similar shape of the stressstrain curve associated with the mechanical behavior of brittle materials. As the Al content increases to 9 wt.%, the stress-strain diagram demonstrates typical characteristic of ductile materials, with a long yielding stage beginning at the yield strength of~44 MPa followed by a strain hardening process. This ductile mechanical behavior has not previously been observed in La(Fe,Si)13composites bonded by other ductile metals such as In,[4]Sn,[14]and Bi,[15]and is also absent in a LaFe11Co0.8Si1.2/10 wt.% Al composite prepared by the hot-pressing method.[6]The present 16.7 wt.% Al sample demonstrates an ultimate compressive strength of 388 MPa,much higher than the values for the hotpressed LaFe11Co0.8Si1.2/10 wt.% Al composite (186 MPa)and 20 wt.% Cu-bonded La0.8Ce0.2(Fe0.95Co0.05)11.8Si1.2(248 MPa).[12]Consolidated alumina powder bodies show particle size-dependent plastic to brittle transition due to the fact that, for a given applied pressure, larger forces exist between larger particles as a result of the smaller number of contacts per unit volume.[16]Smaller wood particle sizes correspond to a higher ultimate compression strength in woodbased composites, as the larger surface area for smaller particles could act as an adhesive factor in the composite system and lead to a more efficient stress transfer.[17]It has been observed in SiC particle-reinforced Al-Cu alloy composites that a small particle size of several microns and uniform distribution of the reinforcing phase corresponded to the highest yield strength and ultimate tensile strength.[18]According to these previous results, the high compressive strength and mechanical behavior of ductile materials in the present La0.5Pr0.5Fe11.4Si1.6B0.2Hy/Al composite can be ascribed to the fact that the ball milling results in Al particles being distributed in the whole matrix as well as the small particle size of the composites.

Fig. 3. Compressive stress-strain curves for La0.5Pr0.5Fe11.4Si1.6B0.2Hy/Al composites.

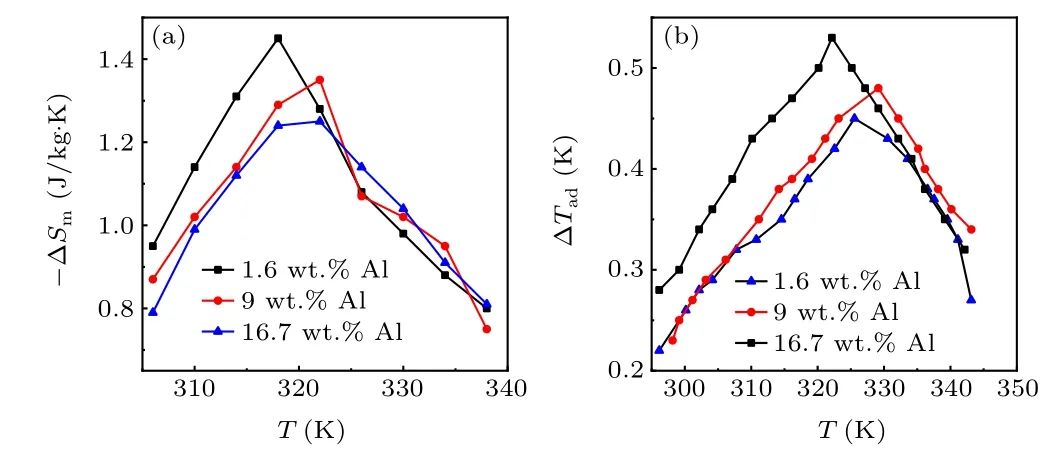

Next, we evaluate the magnetocaloric properties of the Al-bonded composites. The thermomagnetic curves of the composites in a field of 0.01 T are shown in Fig. 4(a). The Curie temperature,TC,defined as the minimum of the dM/dTversusTcurves, is~320 K for the 1.6 wt.% Al sample and~324 K for the two samples with higher Al contents.The temperature dependence of ΔSm(T,B) calculated from the isothermal magnetization data (Figs. 4(b)-4(d)) using the Maxwell relationship is shown in Fig. 5(a). The maximum value of ΔSmof the La0.5Pr0.5Fe11.4Si1.6B0.2Hy/Al composites is reduced by approximately fivefold to~1.2 J/kg·K-1.5 J/kg·K for a magnetic field change of 1.5 T compared with(La,Pr)(Fe,Si)13-based hydrides.[19-21]This can be mainly ascribed to the small particle size[22]due to the ball milling process as well as the existence of non-magnetocaloric phases of Fe-Al-Si alloys and pure Al. The directly measured adiabatic temperature change ΔTadis represented in Fig.5(b). The peak value of ΔTadfor a field change of 1.5 T is 0.54 K at 322 K,0.48 K at 330 K and 0.45 K at 325 K for the 1.6 wt.% Al,9 wt.%Al,and 16.7 wt.%Al composites,respectively.

Fig. 5. The temperature dependence of ΔSm (a) and ΔTad (b) for La0.5Pr0.5Fe11.4Si1.6B0.2Hy/Al composites.

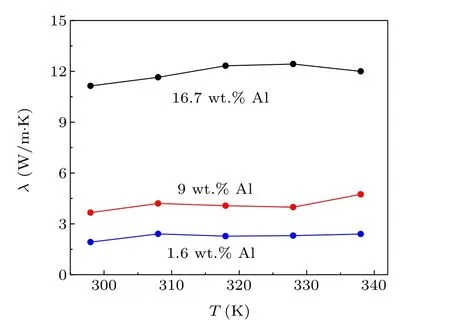

High thermal conductivity of magnetocaloric materials is desirable for application in a refrigerant device in order to afford efficient heat transfer to the heat exchange fluid.Hot-pressing or sintering cannot ensure uniform distribution of thermal conductive metal particles in La(Fe,Si)13hydride matrices, making theλvalues lower than expected, such as 2 W/K·m-3 W/K·m for the 4 wt.% Cu bonded,[3]5 W/K·m for the 15 wt.% silver-epoxy bonded[23]and 6.8 W/K·m for the 25 wt.%Sn bonded[14]composites.Figure 6 represents the thermal conductivity of La0.5Pr0.5Fe11.4Si1.6B0.2Hy/Al composites in the temperature range covering the phase transition temperature. Theλvalues in the paramagnetic state are generally a little higher than those in the ferromagnetic state. The room-temperatureλin the cross-plane direction of the sintered plates is 1.9 W/K·m, 3.7 W/K·m, and 11.1 W/K·m for the 1.6 wt.%,9 wt.%,and 16.7 wt.%Albonded composites,respectively,indicating that metal Al has a similar effect on thermal conductive improvement of La(Fe,Si)13hydrides to metal In.[4]A plastically deformed La(Fe,Si)13plate demonstrated significant anisotropic thermal conductivity in cross-plane and in-plane directions mainly due to the in-plane elongation ofα-Fe and the 1:13 phase grains caused by open-die forging.[24]The present composites prepared by ball milling and shortduration sintering do not exhibit an apparent anisotropic microstructure,so we expect no substantial directional difference inλfor the Al-bonded La-Fe-Si composites.

Fig. 6. Thermal conductivity of La0.5Pr0.5Fe11.4Si1.6B0.2Hy/Al composites at temperatures across the phase transition temperature.

4. Conclusion

We have developed a novel route for the fabrication of La(Fe,Si)13hydride-based bulk materials via ballmilling mixing and sintering at high hydrogen pressure.Upon incorporating 9 wt.%-16.7 wt.% Al, the as-prepared La0.5Pr0.5Fe11.4Si1.6B0.2Hy/Al composites demonstrate the mechanical behavior of ductile materials with a yield strength of 44 MPa and ultimate strength of 269 MPa-388 MPa. The 16.7 wt.%Al-bonded composite has a high thermal conductivity of 11.1 W/K·m,which is comparable to the effect of metal In bonding. The ball milling process facilitates the homogeneous distribution of metal Al in the matrix, but simultaneously reduces the particle size even to the submicron range,leading to a substantial decrease in the magnetocaloric effect.

Acknowledgments

Project supported by the Open Research Project of State Key Laboratory of Baiyunobo Rare Earth Resource Researches and Comprehensive Utilization and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 51771197 and 52171187).

- Chinese Physics B的其它文章

- Helium bubble formation and evolution in NiMo-Y2O3 alloy under He ion irradiation

- Dynamics and intermittent stochastic stabilization of a rumor spreading model with guidance mechanism in heterogeneous network

- Spectroscopy and scattering matrices with nitrogen atom:Rydberg states and optical oscillator strengths

- Low-overhead fault-tolerant error correction scheme based on quantum stabilizer codes

- Transmembrane transport of multicomponent liposome-nanoparticles into giant vesicles

- Molecular dynamics simulations of A-DNA in bivalent metal ions salt solution