新時代的花園城市

著:(加)派特里克·穆尼 譯:江北

0 引言

生態系統服務是指人們從生態系統功能中獲得的產品、服務和利益[1-3]。氣候調節、防洪和授粉等眾多服務是人類生存所必需的[4]。除了這類有形的生態系統服務,與大自然接觸還能帶來改善認知功能、減壓、身心健康等非物質益處,恢復性特性也可被列入生態系統文化服務清單[5-7]。

自有歷史記載開始,園林就被設計成既能夠提供食物等物質生態系統服務,又能提供社交、娛樂和精神體驗等非物質生態系統服務。今天,新的知識讓我們能夠通過景觀設計增加生態系統服務的數量并提高其質量[7]。

盡管城市花園創造了許多生態系統服務,但筆者重點討論兩個彼此協同、至關重要,卻常被城市規劃者和城市設計師忽視的生態系統效益,即城市地區的生物多樣性和人的身心健康。

1 園林簡史

1.1 歷史

在現代語中,“花園”一詞被用來描述與住宅相鄰的空間,這個空間里包含觀賞類植物,可能還有可食用植物,其目的都是支持戶外活動并且與公共領域構建出分離感。此外,在今天,療愈花園也很常見,很多療愈花園隸屬于醫療機構。這些花園為人類身心健康提供保障[8]。在這些方面,現代花園與療愈花園以及人類祖先創造的園林并無區別。

公元前3000年,埃及官員的宅邸花園深藏在墻宇間,墻能保護他們免受野生動物、掠奪者和沙漠狂風的侵襲。早期的花園是實用性的,種有蔬菜、果樹和葡萄藤[9]。隨后發展出裝飾性水景和類型繁多的花卉,實用性的古埃及花園逐漸演進成提供安全和食物,改善微氣候,具有審美體驗、社交和精神寄托的多功能花園。

公元前4000年的古埃及花園和波斯花園都有圍墻、大量水元素和樹木植栽[10]。亞歷山大大帝(公元前356—公元前323)于公元前331年征服波斯帝國,8年后在他去世前,已經把波斯花園從東邊的亞得里亞海和古埃及國傳到了西邊的喜馬拉雅山[11]。正是這個帝國,在公元前7世紀被穆斯林阿拉伯人重新征服時,發展出伊斯蘭花園。穆斯林吸收了查赫巴格花園的形式(或波斯四方花園的形式,即十字形水道在花園中心匯合,把花園分為4個象限),同時賦予伊斯蘭花園《可蘭經》中天堂的象征意味。公元前7世紀—公元16世紀,伊斯蘭花園在伊比利亞半島、西西里島、北非,以及橫跨中東至印度都有跡可查。如同早期的古埃及花園、波斯花園一樣,伊斯蘭花園既是塵世享樂的天堂,也象征著來世的天堂花園[11]。

之后古羅馬花園的設計受到這些早期封閉式花園的影響。古羅馬的私人花園有墻、對稱、有花壇,庭院中的亭子圍繞著中央的灌溉池或渠道[12]。

羅馬人首次記錄下自然恢復力。從羅馬政治家小普林尼(即蓋尤斯·普林尼·采西利尤斯·塞孔都斯,61—112)書信的引言可見,他有多么珍惜自己因接觸大自然而獲得的精神健康和靈感。他寫道:

你想知道我夏天在托斯卡納別墅的日子是怎么過的……大約十點或十一點左右……根據天氣的變化,我要么到露臺上,要么到有頂棚的門廊上,在那我或沉思,或口述……從那里我登上自己的戰車……發現這種場景的變化保持并活躍了我的注意力。

(第9書,36行)

哦,莊嚴的大海、孤寂的海岸,最好也最隱秘的適合沉思的舞臺,你們激勵了我多少博大的思想!

(第1書,9行)

——蓋尤斯·普林尼·采西利尤斯·塞孔都斯(普林尼二世)①

到了中世紀(公元前500—公元1500年),基督教修道院建造出封閉式的花園,讓人想起伊斯蘭花園的形式[13]。修道院的墻壁和被稱為回廊的拱廊包圍著花園,從回廊可以一眼望見花園[14]。小路把花園劃分成幾塊,就像伊斯蘭花園,小路象征著伊甸園的4條河,在花園中心的水井或噴泉處交匯。回廊花園通常與修道院的診療室相鄰,用作治療病患的場所。圣伯納德(1090—1153)這樣描述他在法國克萊爾沃修道院的花園庭院和那里的治療效果:

圍墻里有各種各樣的樹木,它們結滿果實,形成一座名副其實的樹林,緊挨著那些病人的病房,緩解他們的病痛,同時也是一個可心的休息場所,給那些在寬闊人行道上的漫步者以及受酷暑之苦的人們一絲慰藉……可愛的綠色草本植物和樹木滋養著雙眼……巨大的喜悅在他面前懸掛和生長……當空氣帶著明亮的寧靜微笑,大地帶著果實呼吸,而病人帶著眼睛、耳朵和鼻孔,品嘗著顏色、歌曲和香水的喜悅。

——圣伯納德[14]

這段話所表達的觀點是:大自然中的美值得珍視,它能帶來幸福,在整個人類歷史上向來如此[15-16]。在古羅馬和中世紀的歐洲,花園被認為是和平、療傷和靈感來源的場所。還必須指出的是,普通人一般無法進入那些富人和教會修建的花園。這類花園,無論是小園子還是大莊園,許多都被墻圍起來,以便讓花園和里面的居民與外界隔開。它們既具有實用性,又是自然美的理想化表現,用于提供食物、審美享受、社交、休憩和幸福感。

1.2 浪漫主義的理想化景觀

18世紀的浪漫主義哲學家,如讓–雅克盧梭(1712—1778)和亞歷山大·波普(1688—1744)支持這樣的觀點:與自然的接觸表明了人類本質上的善良,有助于個人的寧靜和幸福[17-18]。他們的作品啟發了北歐和英國的上層階級去創造奢華的鄉村莊園。在浪漫主義的影響下,這些非正式的莊園場地,或所謂的公園,旨在通過喚起人們對自然美景的情感反應來提升人類的思想和福祉。

1.3 城市公園

歐洲、英國和北美城市公園的發展也受到浪漫主義的影響。新的公園被提倡作為改善公民健康、福祉和城市風貌特色的一種手段[19]。弗雷德里克·勞·奧姆斯特德表示,公園“為消除都市罪惡提供了條件”,并有助于使游客的思想“遠離先前導致精神緊張或精神疲勞的實體,更有利于沉靜地思考”[20]。

奧姆斯特德在這份報告中表達了從浪漫主義者那里繼承的觀點,即人類通過接觸城市公園里的自然而獲得積極的精神效益。在他看來,花在公園里的時間,使市民能夠恢復他們的心智[21],不僅如此,接觸城市公園還能將花園的療愈效果擴展到那些社會經濟地位低的底層人群,他們原本可能因為沒有私人花園,而無法獲取這些療效[22]。

很明顯,奧姆斯特德和浪漫主義哲學家們正確地認識到了與自然接觸的好處。在過去的幾十年里,研究人員發現了與大自然接觸所帶來的多種精神和身體上的好處。這些措施包括:減少壓力、降低犯罪率和家庭暴力發生率、顯著降低各種疾病發病率、改善情緒和提高心智能力、增加仁愛,還能改善注意力缺陷多動障礙[6,23]。此外,研究人員還報告說,兒童時期接觸大自然有助于促進健康發展、改善幸福感并提高對自然美的欣賞[24]。在與自然的接觸中,社會經濟地位較低的人和兒童可以獲得更大的益處[23,25]。

2 城市增長與密度效應

在世界范圍內,越來越多的人搬到城市里。據估計,到2050年,全球城市人口占全球總人口的比例將從目前的55%提高到68%,全球城市人口將增加25億。到2030年,超過1 000萬人口的城市數量將從目前的33個增加到43個②。隨著城市密度的增加,私人花園的數量和面積將減少,取而代之的是公共開放空間(public open space, POS)的增加[26]。

按照目前的趨勢來看,在未來幾十年內,城市人口的急劇增加將導致花園和其他綠地的減少,隨之而來的是城市地區生物多樣性的減少,以及越來越多的城市居民的身心健康的下降。然而,這并非不可避免。

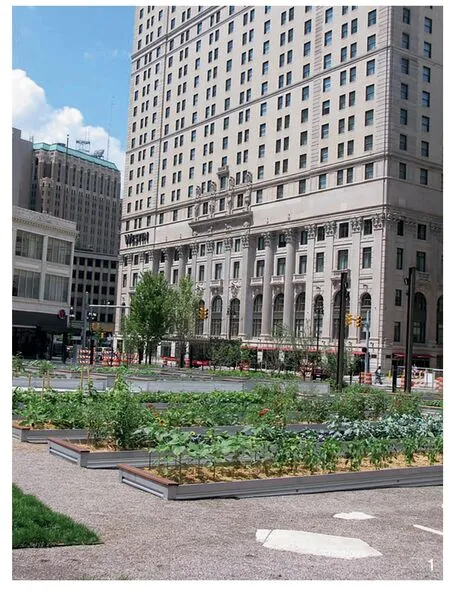

人口密度超過7 500人/km2的新加坡,自稱“花園中的城市”,以綠色建筑和不斷增加的綠地而聞名[27]。1986—2007年間,新加坡人口增長的同時,其綠地率也從36%增長到47%[28]。像新加坡和香港這樣的人口密集的城市,地面綠地空間有限,導致出現了更多的綠色建筑和綠墻[29]。像底特律這樣經歷了嚴重衰落的城市,城市復興能在之前的建筑工地上發展出新的城市綠地(urban green space, UGS,圖1③)[30-31]。

1 底特律的拉斐特綠地社區花園建立在歷史建筑的原址上Lafayette Greens Community Garden in Detroit was built on the site of a historic building

2.1 生物多樣性和生態系統服務

直到最近幾年,風景園林專業才開始將生態系統服務納入景觀設計中。例如,美國風景園林師協會的場地可持續性設計行動計劃(SITES)④和美國風景園林基金會(LAF)⑤的景觀績效系列都旨在促進將生態系統服務納入景觀設計中。這種景觀被稱為績效景觀或多功能景觀。常見的與公共綠地相關的生態系統服務研究,包括碳儲存、風暴和洪水防護、緩解城市熱島效應和維護土壤健康[28]。

“biodiversity”一詞是“biological diversity”的縮寫,簡言之是地球上所有生物的多樣性[32]。它包括所有有機體、物種和生態系統的遺傳多樣性。生物多樣性對我們很重要,因為它支持著地球上所有生物的生命,包括人類。生物多樣性盡管不是一種生態系統服務,但在提供生態系統服務方面具有重要作用,因此將其納入了大多數生態系統服務評估中,而生態系統服務是生物群或生物與其環境相互作用的結果[33]。

已有研究在生物多樣性與支持和調節生態系統服務之間建立了明確的聯系[34]。例如,生物生產力或特定地區產生的凈生物量是一種支持性的生態系統服務,與生物多樣性密切相關[35]。在地方一級,生物多樣性的下降可能意味著魚類或蝦等食物種類的減少,同時喪失的還有碳封存能力或自然抗洪能力。例如,在生態健康的森林中,生物生產力與降水的截留和滲透是相關的。如果該森林因自然或人為力量退化,其生物生產力將下降,同時其攔截、儲存雨水的能力也將下降,從而降低防洪生態系統服務[33]。正如這個例子所說明的,生物多樣性的喪失往往與一個或多個生態系統服務功能的降低有關。

2.2 城市增長和生物多樣性喪失

即使科學家和城市規劃者也普遍存在一種誤解,即在城市規劃和發展中,維持生物多樣性并不合理,因為城市地區的生物多樣性較低。然而研究表明,人們通常定居在生物多樣性高的地區,許多城市仍然保留著高水平的生物多樣性[36-38],城市綠地對于支持區域生物多樣性至關重要[39-40]。科學家們報告說,城市擴張降低了當地的生物多樣性[41],并預測除非當前趨勢發生變化,否則2012—2030年期間因城市擴張將再破壞120萬km2的綠地。這種土地覆被變化將導致棲息地喪失、生物量和碳儲量減少,威脅全球生物多樣性[42]。

衡量生物多樣性的一個常用指標是物種豐度或某一特定地區不同物種的數量。因此,物種的滅絕是生物多樣性總體喪失的有力指標。據估計,由于人類活動,如空氣和水污染,城市化、農業擴張和采礦、伐木造成的棲息地破壞,物種正在以自然狀態下1 000倍的速度加速滅絕,許多可能作為新藥開發或維持農業穩定性的物種正在消失,而它們從未被記錄在案[43]。這被稱為地球歷史上第六次大滅絕。大型哺乳動物的滅絕已被廣泛報道,但對生態系統功能至關重要的昆蟲的滅絕速度是哺乳動物的8倍[44],而其中傳粉昆蟲的減少也許是最令人擔憂的。地球上85%以上的植物由昆蟲和其他動物授粉,全球75%的主要糧食作物需要授粉[45]。與農田一樣,自然區域現在也處于授粉不足的狀態,降低了植物繁殖率,威脅了本地植物的生物多樣性[46]。一項全球生物多樣性喪失調查報告稱,有30%的鳥類、哺乳動物和爬行動物以及15%的兩棲動物數量在下降;這項報告警告,在地球的生命維持系統受到不可挽回的損害之前,人類還有20~30年的時間采取行動[47]。另一項研究報告表明,目前21%的鳥類物種正面臨滅絕的危險,如果當前的趨勢不逆轉,全球生態系統服務很可能喪失[48]。

在我們的集體意識中,這種問題與氣候變化不可相比,但它可能是個更加嚴峻的問題。原因有兩個:1)總有一天,當人類不再排放溫室氣體,氣候將會緩慢趨于穩定,但物種滅絕卻無可挽回[32];2)由于生物多樣性與生態系統服務有關,就人類在地球上的生存問題而言,生物多樣性的喪失很有可能比氣候變化的影響要更大。我們無法知道何時生物多樣性的下降將會導致生態系統的崩潰或生態系統服務的喪失。因此,維護生物多樣性符合人類自身利益[4]。

2.3 城市增長與綠地

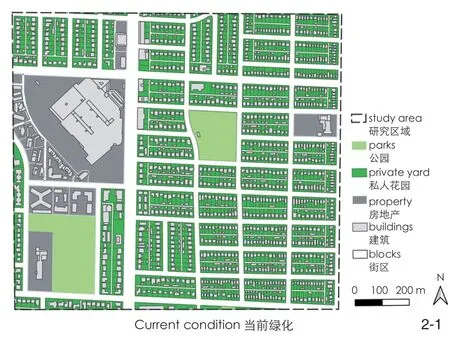

紐約、東京、孟買、墨西哥城和溫哥華等許多大都市地區的發展會受到地理條件和(或)規劃政策的制約(圖2)。這意味著,隨著人口的增加,這些城市應該將密集化作為首要發展戰略,而不是向周圍農村地區擴張,因為城市化不僅增加了城市的碳足跡范圍,還會減少生物多樣性和生態系統服務[42]。緊湊型城市被認為是城市擴張的替代方案,具體策略包括高效的公共交通、普及自行車的使用,以及鼓勵步行[49]。

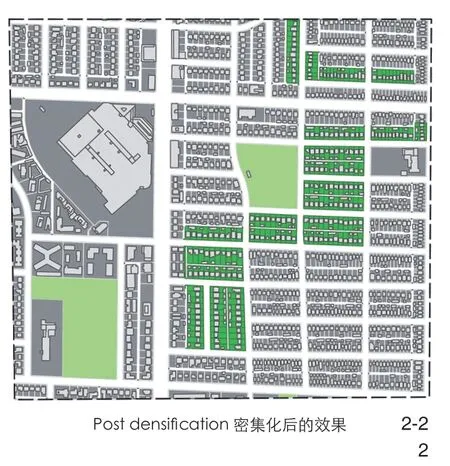

隨著城市密度的增加,現有的低密度街區將被高密度的開發項目所填充。多戶住宅將取代獨棟住宅。包含私人花園的住宅類型將超出許多業主的財力負擔范圍,甚至不符合他們的期望,提供這類住宅將導致城市擴張,而不是密集化。當這種情況發生時,城市居民將得不到私人花園的恢復性效益。

雖然在歷史上人類發展減少了生物多樣性,但在許多地方,花園和果園對區域生物多樣性產生了相當大的積極影響[50]。在現代城市中,在城市郊區創造的各種公共和私人景觀,承擔了生態演替階段的早期景觀載體,為許多鳥類提供棲息地。研究人員報告說,雖然城市核心區的鳥類物種數量非常低,但郊區花園和公園的鳥類和蝴蝶的種類和個體數量顯著增加[51-53]。

2-1 加拿大溫哥華正在密集化街區的綠地狀況The current green space in a neighbourhood that is undergoing densification in Vancouver BC, Canada

2-2 密集化后的效果。灰色顯示的是所有因重建而消失的私人花園Post densification. It shows in grey all the private gardens that will be lost to redevelopment

更大、更擁擠、更高密度的城市將剝奪大多數居民擁有私人花園以及花園附帶的各種生態系統服務。若要想提供這類好處給未來的城市居民,就必須開發新的公共綠色基礎設施,以保護身心健康,而不僅限于城市私人花園和傳統公園的服務范疇。

然而,評估生態系統服務和綠色基礎設施等概念的生物、生態或技術功能的研究很多,但評價福祉和健康相關的研究很少[54]。同樣,大多數城市綠色基礎設施提案都是單一目的的,沒有自覺地納入生物多樣性或公共衛生,例如《溫哥華市雨城戰略》[55]。如果未來的城市要支持人類福祉和區域生物多樣性,就需要在這一點做出改變。

除非未來密集的特大城市本身能成為生物多樣性豐富的療愈花園,否則將對人類福祉產生廣泛的負面影響。相反,如果將這兩個問題納入城市規劃和發展的考慮范圍內,未來城市就可以起到保護生物多樣性并提供生態系統服務的作用,可以增加人類福祉。然區域、市政花園、市民廣場和學校場地[28]。UGS包含了城市中的所有植被區域,如私人花園、公園、高爾夫球場和行道樹區域[56]。與POS的重要區別在于,UGS可以提供生物多樣性、與之相關的生態系統服務以及與自然接觸的健康和福祉。因此,為了實現城市地區的健康和生物多樣性,應關注UGS而不是POS。這意味著要綜合考量公共和私人開放空間。研究人員報告說,在富裕的街區,綠地可達性通常更高[57]。為了使UGS效益公平,其分布將需要與大都市地區的城市密度相關。

3.1 生物多樣性與心理恢復

3 作為花園的城市

城市綠地(UGS)將如何彌補密集化城市中私人花園(減少)帶來的損失?公共開放空間(POS)包括公共領域內的公園、操場、自

重要的是要了解生物多樣性和與自然的接觸的精神恢復是協同關系。研究人員對生物多樣性與恢復之間的關系進行研究,結果表明:生物多樣性豐富的環境更具恢復性(圖3~5)[58-60]。這與所謂的親生物假說所認為的人天生就傾向于親近自然相符[61]。其他研究者的報告指出,自然環境中增加生物恢復指標,并不會讓生物多樣性增加[62]。景觀中鳥類物種多樣性是總體生物多樣性的有力指標[63-64]。因此,提高鳥類的生物多樣性可以增加總體生物多樣性,同時也和人類親生物本能緊密相關,是恢復性景觀的標志。

3 英屬哥倫比亞省維多利亞市多功能雨水公園。一個不僅僅能凈化都市徑流的小型的自然社區公園Two views of a multipurpose rain garden park in Victoria BC. Instead of just cleansing urban runoff before it enters the ocean, a small naturalistic neighbourhood park has been created

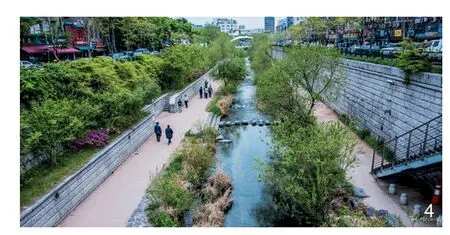

4 韓國首爾的清溪川景觀改造,是城市主動開創大型城市綠地的范例。這里曾是一條高架高速公路,現在是一條活躍的娛樂休閑步道,支持生物多樣性和身心健康Cheong Gye Cheon Canal Street in Seoul, South Korea, is an example of finding new opportunities for urban green space. This site of a former elevated freeway is now an active recreation corridor that supports both biodiversity and wellbeing

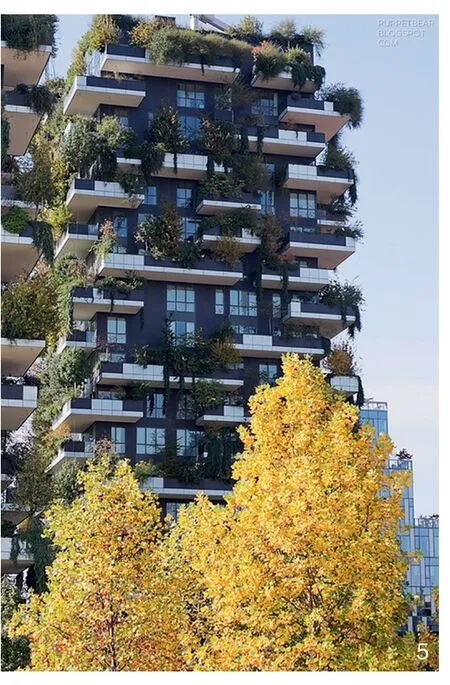

5 博埃里工作室設計的米蘭博斯科垂直住宅樓栽植了900多棵樹。在城市綠地受限的地方,這種親生物設計有利于精神恢復Bosco Verticale residential towers in Milan designed by Boeri Studio contains more than 900 trees. Where urban green space is limited this type of biophilic design provides restoration

就自然的恢復特性而言,恢復能力和偏好密切相關。人們普遍更喜歡偏自然感的環境,可以通過預測精神恢復能力的景觀元素預測人的偏好,反之亦然[65-66]。神秘性的本質——即深入其中才會發現更多,這也是預測景觀偏好和精神恢復的因素[66-68]。在“綠化”水平的研究中,研究者發現更綠色的環境中,獲取的恢復性福利更可靠或更大[69-70]。

一個人越是置身于風景之中,他的心理活動就會越活躍[71],研究表明,高參與程度能夠帶來強精神恢復能力[72]。一般來說,增加接觸自然環境的時間和頻率會促成高恢復水平[73-74],因此城市居民在當地UGS上花費的時間越多,對UGS使用頻率越高,他們得到的恢復效果就越顯著。

瑞典阿爾納普市景觀規劃健康與娛樂研究所的研究人員認為,花園必須是有四壁和天花板的室外空間,主導元素必須是植物,它們還要能帶來生命感,讓人感受到季節周期性的變化,從而傳達平和、感官刺激和美感。此外,研究者表示,療愈花園要能激活所有感官,不僅有視覺,還有嗅覺、味覺和觸覺,療愈花園隨著時間的推移呈現出一系列特征,它給人以整體感,在這里,人與外界分離,具有安全感[75]。

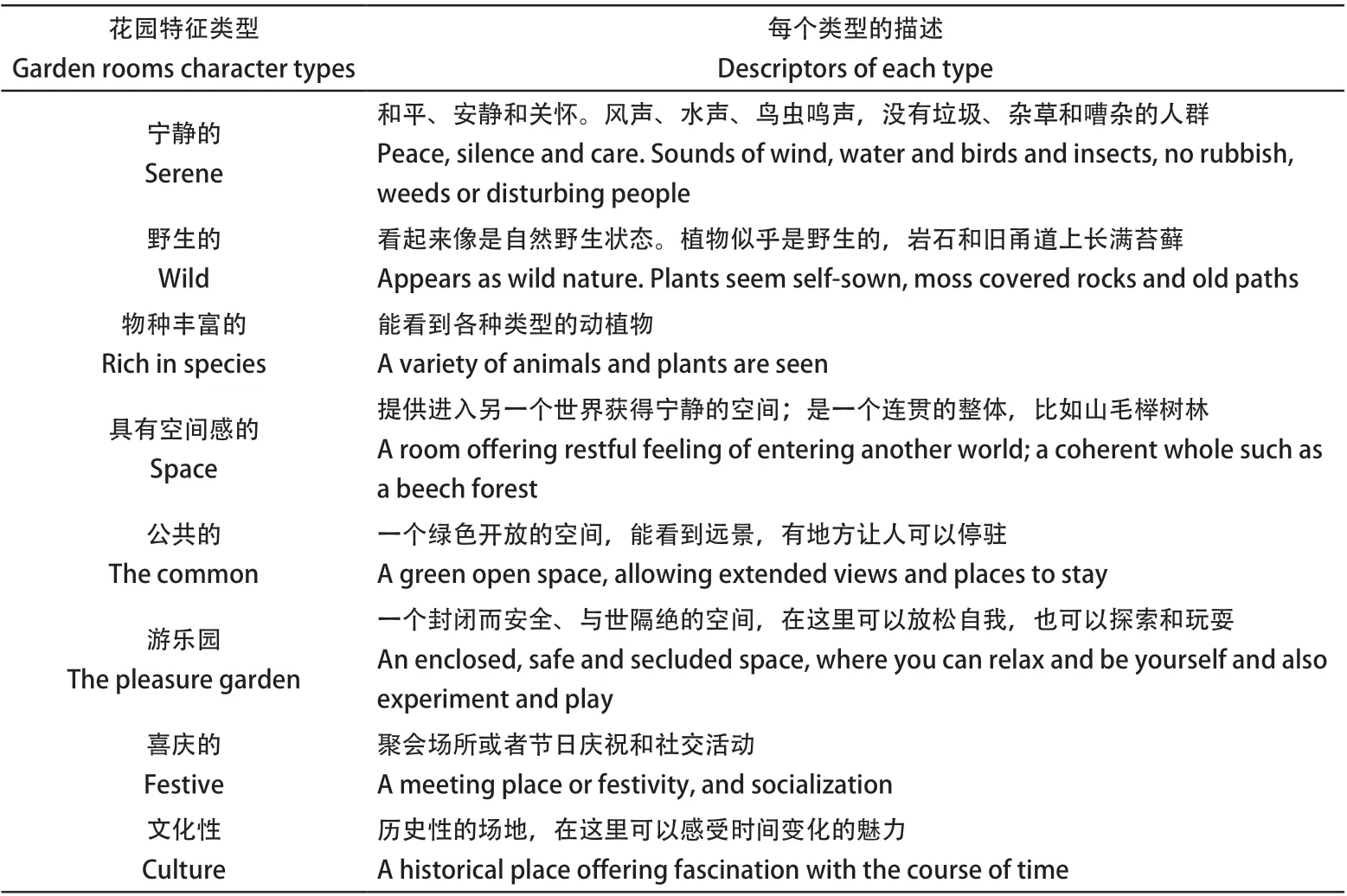

這些研究人員還逐漸意識到,特征繁多的公園比只有單一特征的公園能吸引更多人,而且某些類型的特征通常比其他類型更吸引人,這又一次證明生物多樣性與偏好/恢復之間的協同作用。研究表明,隨著生物棲息地多樣性的增加,即某一地點不同類型棲息地的數量增加,生物多樣性也會增加[53]。研究人員將花園特征分為8種類型(表1)。

表1 花園特征類型及描述[75]Tab. 1 Character types of garden rooms and their descriptions[75]

他們發現,寧靜、具有空間感和物種豐富的花園吸引的訪客更多,而公共花園和游樂園則吸引了壓力較小、希望觀看他人的訪客。此外,他們還報告說,呈現前一組特征(寧靜、空間感、物種豐富)需要自然區域,有許多不同種類的植物和高大的樹木。

3.2 策略

許多研究人員和設計師已經為生物多樣性更豐富的城市區域或更具恢復性的城市環境提出了建議,感興趣的讀者可以自行查看這些建議,因為它們超出了本文的范圍[23,28,76-77]。從他們的建議和筆者的調查中,可以得出一些原則。雖然這些研究并不全面,但它們具有廣泛的適用性,并以實證研究為基礎。1)區域網絡:將行動與規模聯系起來。許多城市地區是生物多樣性的熱點地區。為此,應該規劃和實施一個區域生態網絡。這將保護并關聯該地區稀有和代表性的生物多樣性。UGS可以支持區域生物多樣性,因而不應只在有條件的情況下增加UGS,而應將其作為維持棲息地類型多樣性的整體區域戰略的一部分[22,78]。這一策略將產生一系列不同規模和類型的UGS,使人們能夠進入更荒野的地區,增加人們體驗到的景觀類型,適應不同的UGS使用者,并增加人類福祉[59]。2)小貼士(cues to care):許多生物多樣的景觀未必符合文化習俗。可以實施一系列“小貼士”,以表明景觀是特別規劃的,并且是有管理的。這將有助于提高公眾接受度[75,79]。3)使UGS成為一系列有區別但關聯的空間[75,80]。4)從政策到設計:不要只依賴寬泛的政策。特別是在規模較小的空間下,需要特定的設計指令。例如,在鄰近地區,為鳥類和昆蟲,特別是傳粉昆蟲及其棲息地的恢復提供一系列景觀特征。這些不同的棲息地將增加生物多樣性,還將提供多種景觀體驗[22,53]。5)親近自然:讓自然近在咫尺,無處不在。通常不可能新建大型UGS,但在醫院、監獄、家庭和工作場所的景觀中栽植行道樹或其他植物是可能的,它們將是提供恢復效益的重要貢獻者[81-84]。6)公共及私人區域的融合:打破公私區域之間的壁壘,為了公共利益而塑造私人的綠地[85]。考慮UGS在公共和私人區域能協同發揮作用。建立多元化的私人花園“互通網”,促進野生動物和傳粉物種的交流。7)整個城市要公平地分配綠地[57]。8)更多的綠地:提高城市開放空間、城市綠地的比例。許多城市對開放空間有很高的要求,但未能確保開放空間是綠色的,并可供公眾使用。在大型住宅開發項目中,將私人綠地的一部分開放給公眾[7]。9)在城市中為小型區域賦予功能性和自然性[27]。10)打造城市森林:種植大樹以及垂直方向層次豐富的森林有利于生物多樣性[86]。11)將本地和非本地植物混合種植,能讓鳥類和授粉物種受益。UGS的種植應多樣化,并混合適合當地的非本地和本地植物。植物種類多樣性將支持傳粉物種[22,87-88]。12)人們越深入地參與自然,從中收獲的健康效益就越大[22]。城市綠地的規劃、設計和實施,要能夠鼓勵人們積極參與管理,就像他們以前管理私人花園那樣。這可能意味著一系列的變化,例如住宅開發中會有更密集的屋頂花園,集合住宅的業主開始關心公共景觀,更多的社區花園遍布整個城市,學校的孩子們參與鳥巢箱計劃。13)使所有新的綠色基礎設施支持多種生態系統服務。雨水花園和生物沼澤可以是親近自然的方式,讓城市有更好的生態修復能力,還能凈化雨水。14)將UGS集中在人群密集的地方,比如機場、醫院、學校、工作場所和通勤走廊[23]。

注釋:

① 引自http://www.vroma.org/~hwalker/Pliny/PlinyNumbers.html。

② 引自https://www.un.org/development/desa/en/news/population/2018-revision-of-world-urbanization-prospects.html。

③ 密歇根州底特律市在失去大企業和稅源后于2013年宣布破產,許多城市核心區都被遺棄。如今,許多街區正在復蘇,部分曾經的建筑工地變成了城市綠地。肯尼思·韋卡爾景觀設計公司設計的拉斐特綠地社區花園獲得美國風景園林師協會大獎,項目位于原底特律市中心的拉斐特大樓所在地,該大樓于2010年被拆除。康博軟件公司于2014年捐贈這個花園給非營利組織“底特律綠化”(The Greening of Detroit)。這個花園不僅用于社區食品生產,還支持社區聚會活動,適合作為兒童花園,可作為傳粉物種的棲息地。

④ 引自https://www.asla.org/sites/。

⑤ 引自https://www.landscapeperformance.org。

圖表來源:

圖1引 自 https://www.asla.org/2012awards/073.html;圖2由Charlotte Chen、Marco Leung和Alwyn Rutherford拍攝;圖3由經默多克·德萊夫公司景觀設計師許可使用;圖4由Ted McGrath提供,在知識共享許可下使用;圖5由Ty提供,在知識共享許可下使用。表1引自參考文獻[75]。

(編輯/劉玉霞)

Garden Cities in the New Millenia

Author: (CAN) Patrick Mooney Translator: JIANG Bei

0 Introduction

Ecosystem services are the goods, services and benefits that people receive from the functions of ecosystems[1-3]. Many of these services like climate regulation, flood control and pollination are necessary for human survival[4]. In addition to these material ecosystem services, the non-material benefits of improved cognitive functioning, stress reduction, psychological and physical wellness that result from the restorative properties of contact with nature may be added to the list of cultural ecosystem services[5-7].

Since the dawn of recorded history, gardens have been designed to supply material ecosystem services like food and non-material ecosystems services like socialization, recreation and mental restoration.Today new knowledge allows us to increase the number and degree of ecosystem services that can be derived from designed landscapes[7].

Although there are many ecosystem services that accrue from the urban gardens, I will focus in this essay on two ecosystem benefits that are synergistic, critically important and that are often overlooked by city planners and urban designers:biodiversity in urban regions and human mental and physical wellbeing.

1 A Brief History of Gardens

1.1 History

In modern discourse, the term garden is used to describe a space adjacent to the residence that contains ornamental, and possibly food plants and that is intended to provide outdoor activity and separation from the public realm. In addition, it is now common to hear of healing gardens, many of which are attached to health care institutions.These are gardens that support mental and physical wellbeing[8]. In these respects, modern gardens do not differ from those or our ancestors.

In 3,000 BC, the home and garden of an Egyptian official were contained within a wall that provided protection from wild animals,marauders, the desert winds. Originally, the garden was utilitarian, growing vegetables, tree fruits and grape vines[9]. With the development of decorative water features and abundant flowers,the utilitarian ancient Egyptian garden evolved into a multi-purpose garden that offered safety, food,microclimate modification, aesthetic enjoyment,socialization and repose.

The ancient Egyptian garden and the Persian garden (c. 4,000 BC) were both walled gardens with extensive water features and trees[10]. Alexander the Great (356–323 BC) conquered the Persian Empire in 331 BC and by the time of his death eight years later, had transmitted the Persian garden from the Adriatic Sea and Egypt in the east to the Himalayas in the west[11]. It was this empire that, when reconquered by Muslin Arabs the 7th century BC,developed the Islamic Garden. The Muslims absorbed the Chahar Bagh, or four-garden, form of the Persian garden i. e. , a garden divided into quadrants by cruciform water channels meeting in the center of the garden, but ascribed to it the meaning of the afterlife paradise described in theQuran. Between the 7th century BC and the 16th century AD, iterations of the Islamic garden were created in the Iberian Peninsula, Sicily, north Africa,and across the Middle East to India. Like the earlier ancient Egyptian and Persian gardens, the Islamic garden was both a worldly pleasure garden and a simulation of an afterlife paradise[11].

Later the design of ancient Roman gardens was influenced by these earlier enclosed gardens.In ancient Rome, a private garden was a walled,symmetrical, treed courtyard with flower beds, in which pavilions were arranged around a central irrigation pool or channel[12].

The Romans were the first to leave a historical record of the restorative powers of nature. Quotes from the Letters of Roman statesman Pliny the Younger (c. 61 AD – c. 112 AD) illustrate how much he treasured the mental restoration and inspiration that he received from contact with nature. He wrote….

You desire to know in what manner I dispose of my day in summer time at my Tuscan villa. …About ten or eleven of the clock… according as the weather recommends, I betake myself either to the terrace, or the covered portico, and there I meditate and dictate… From thence I get into my chariot…and find this changing of the scene preserves and enlivens my attention. (Book nine, Letter 36)

Oh solemn sea and solitary shore, best and most retired scene for contemplation, with how many noble thoughts have you inspired me! (Book one, Letter 9)

—Gaius Plinius Secundus (Pliny II)①

In in the Middle Ages (c. 500–1500 A. D.),Christian monasteries built enclosed gardens reminiscent of the form of Islamic garden[13].The gardens were enclosed by the walls of the monastery and covered arcades known as cloisters that provided views into the garden[14]. Like the Islamic garden, these gardens were divided into by paths symbolizing the four rivers of Eden that intersected at a well or fountain in the center of the garden. Often, the cloister garden was adjacent to the monastery infirmary and was used as a place of healing. Saint Bernard (1090–1153) described the courtyard garden of his monastery at Clairvaux France and its healing benefits.

Within this enclosure, many and various trees,prolific with every sort of fruit, make a veritable grove, which lying next to the cells of those who are ill, lightens with no little solace the infirmities of the brethren, while it offers to those who are strolling about a spacious walk, and to those overcome with heat, a sweet place for repose… The lovely green of the herb and tree nourishes his eyes… their immense delights hanging and growing before him… while the air smiles with bright serenity, the earth breathes with fruitfulness and the invalid himself with eyes, ears and nostrils, drinks in the delights of colours, songs and perfumes.

—Saint Bernard[14]

The ideas expressed in this quote, i.e., that the beauty found in nature is to be prized and that it bestows wellbeing have been consistent throughout human history[15-16]. In ancient Rome and mediaeval Europe gardens were understood to be places of peace, healing and inspiration. It must also be noted that these gardens, built by the wealthy and the church were generally unavailable to the common person. Many of these gardens, whether smaller gardens or estates, were enclosed by a wall that separated the garden and its inhabitants from the outside world. They were simultaneously utilitarian gardens and idealized representations of the beauty of the natural world and were intended to provide food, aesthetic enjoyment, socialization, respite and wellbeing.

1.2 The Romantic Landscape Ideal

In the 18th century, Romantic philosophers like Jean-Jacque Rousseau (1712–1778) and Alexander Pope (1688–1744) espoused the idea that contact with nature revealed the essential goodness of human beings and contributed to an individual’s serenity and wellbeing[17-18]. Their writings inspired the upper classes of northern Europe and Great Britain to the create lavish country estates. Under the influence of Romanticism, these informal estate grounds, or parks as they were called, were intended to elevate human thought and wellbeing by evoking an emotional response to the beauties of nature.

1.3 City Parks

The development of urban parks in Europe,Britain and North America was also influenced by Romanticism. New parks were advocated as a means to improve the health, welfare and character of citizens[19]. Frederick Law Olmsted claimed that parks “provide for counteracting the special evils that result from the confinement of life in cities”and help to turn visitor’s thoughts “away from the mental contemplation of objects associated with conditions which have produced previous strain or mental fatigue”[20].

In this statement, Olmsted is expressing the idea, inherited from the Romantics, that positive mental benefits accrue to human beings from contact with the nature found in urban parks. In his view, time spent in parks, enabled citizens to restore their mental capacities[21]and were a means of extending the healing effects of gardens to the lowest socio-economic members of society who otherwise could not attain them, because they did not have gardens[22].

It is now evident that Olmsted and the Romantic philosophers were correct in identifying the benefits of contact with nature. In the last several decades, researchers have identified multiple mental and physical benefits that accrue from contact with nature. These include, stress reduction, lower crime and domestic violence,significant reduction in all manner of illness and disease, improved mood, and cognition, increased benevolence and reduction in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder[6,23]. In addition, researchers report that time spent in nature during childhood promotes, healthy development, improved wellbeing and greater value for the environment[24]. People of lower socio-economic status and children receive the greatest benefits from contact with nature[23,25].

2 The Effects of Urban Growth and Densification

Worldwide, more and more people are moving to cities. It is estimated that by 2050, the percentage of global population living in cities will increase from the current 55 percent to 68 percent of the total global population, adding an additional 2. 5 billion people to cities worldwide. By 2030, the number of cities of over 10 million people will rise from the current number of 33 to 43②. As cities densify, the number and area of private gardens is reduced and is not replaced through an increase in public open space (POS)[26].

If current trends continue, the dramatic increase of urban populations that will occur in the next few decades will result in a reduction of gardens and other green spaces with an attendant reduction in biodiversity of urban regions and a decrease in the mental and physical wellbeing of the increasingly large number of people living in cities. However, this is not inevitable.

Singapore, with a density of more than 7,500 inhabitants per square kilometre, refers to itself as The City in a Garden and is noted for its green buildings and adding green space[27]. Between 1986 and 2007, Singapore increased its green space from 36% to 47% while increasing its population[28]. In dense cities like Singapore and Hong Kong, limited opportunities for ground-level green space have led to more green roofs and building facades[29].In cities like Detroit that have experienced severe urban decline, regrowth is leading to new urban green spaces (UGS) being developed on former building sites (Fig. 1③)[30-31].

2.1 Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services

Only within recent years has the profession of landscape architecture embraced the incorporation of ecosystem services in designed landscapes. For example, The American Society of Landscape Architects SITES initiative④and the American Landscape Architecture Foundation, Landscape Performance Series⑤are both intended to foster the inclusion of ecosystem services in designed landscapes. Such landscapes are referred to as performance landscapes or multi-functional landscapes. Commonly reported ecosystems services associated with POS include carbon storage, storm and flood protection, mitigation of the urban heat island effect, and the maintenance of healthy soils[28].

The term biodiversity is a contraction of biological diversity is most easily understood as the variety of all life on earth[32]. It includes all organisms, species and ecosystems in all their genetic diversity. It matters to us because it is the life and life support of all living creatures on earth,includinghomo sapiens. Although biodiversity, is not an ecosystem service, it is included in most ecosystem services assessments because of its importance in providing ecosystem services that are the result of interactions between biota or living organisms and their environment[33].

Research has established a clear linkage between biodiversity and supporting and regulating ecosystem services[34]. For example, bioproductivity or the net biomass produced in a given area is a supporting ecosystem service that is shown to be strongly related to biodiversity[35]. At a local level, a decline in biodiversity might mean a decline in food species like fish or shrimp, a reduction in carbon sequestration or a loss of flood protection. For example, in a healthy forest, bioproductivity and the interception and infiltration of precipitation are correlated. If that forest were to be degraded by natural or human forces, its bioproductivity would decline, together with its ability to intercept, store and distribute rainfall, resulting in a reduction of the ecosystem service of flood control[33]. As this example illustrates,a loss of the biodiversity will often be related to a reduction in one or more ecosystem services.

2.2 City Growth and Biodiversity Loss

It is a common misconception, even among scientists and urban planners, that maintenance of biodiversity in not a legitimate concern in urban planning and development since urban regions are low in biodiversity. However, research reveals that people have usually settled in areas of high biodiversity, that many cities still retain significant biodiversity[36-38]and that urban green spaces are important for supporting regional biodiversity[39-40].Scientists report that urban expansion reduces local biodiversity[41]and predict that unless current trends change, urban expansion will destroy an additional

1.2 million square kilometres of greenfield sites between 2012 and 2030. This land cover change will result in habitat loss, reduction in biomass and carbon storage and threatens biodiversity at a global scale[42].

One commonly used measure of biodiversity is species richness or the number of different species in a particular area. For this reason, loss of species is a strong indicator of total biodiversity loss. It is estimated that due to human activities like pollution of air and water, habitat destruction caused by urbanization, agricultural expansion and mining and logging humans are now exterminating species at 1,000 times the natural rate and many species that might yield new medicines or agricultural stability are being lost without ever being recorded[43]. This has been termed the 6th great extinction in the history of planet earth. The losses of larger mammals are widely reported but insects which are essential to the functioning of ecosystems are declining eight times faster than animals[44]. Of the decline in insects, the decline in pollinators is perhaps most concerning.More than 85% of plants on earth are pollinated by insects and other animals and 75% of major global food crops need pollination[45]. As well as farmlands,natural areas are now under-pollinated reducing plant reproduction and threatening native plant biodiversity[46]. A global examination of biodiversity loss reported that 30% birds, mammals, and reptiles and 15% of amphibians were declining and warned that humanity has two to three decades to act before the life support system of the planet is irrevocable harmed[47]. Another study reported that 21% of all bird species are currently in danger of extinction and that if current trends are not reversed, global loss of ecosystem services is likely[48].

This situation is not in our collective consciousness to the same degree as climate change but it may be considered a greater problem. There are two reasons for this: at some point, humanity will eliminate greenhouse gas emissions and climate will slowly stabilize, however loss of a species is irrevocable[32]. Because biodiversity is related to ecosystem services, its decline may well have a greater effect on the ability of humans to inhabit the earth than climate change. We cannot know the point at which declining biodiversity will result in the collapse of an ecosystem or the loss of ecosystem services. It therefore in the self-interest of humanity to maintain biological diversity[4].

2.3 City Growth and Greenspace

The growth of many metropolitan regions such as New York, Tokyo, Mumbai, Mexico City and Vancouver, is constrained, either by geography or planning policies or a combination of the two(Fig. 2). That means that rather than sprawling over the surrounding countryside, these cities will densify as their populations increase. Where densification, rather than sprawl in not necessitated by policy or geography, it should be the preferred growth strategy of choice, because urbanization that increases the area of the urban footprint also reduces biodiversity and ecosystem services[42].The Compact City is advocated as an alternative to urban sprawl that will incorporate efficient public transport and promote cycling and walking[49].

As cities densify, existing low-density neighbourhoods will be infilled with higher-density developments. Multi-family developments will replace single-family detached housing. The kinds of homes that would allow private gardens will be beyond the means, or even the desires of many home owners, and providing them would result in urban sprawl rather than densification. When this occurs, the restorative benefits of the private gardens will be unavailable to the urban dweller.

While human development has historically reduced biodiversity, in many places gardens and orchards have had considerable positive effect on regional biodiversity[50]. In modern cities, a variety of public and private landscapes created, in city suburbs,act as a surrogate for early seral stage landscapes that provide habitat for many bird species. Researchers report that while the number of bird species in the urban core is very low, the number of birds and butterfly species and individuals increases significantly in suburban gardens and parks[51-53].

Bigger, more congested, denser cities will deprive most of their residents of private gardens and the range of ecosystems services that those gardens provide. In order for these benefits to be provided to future urban dwellers, new public green infrastructure must be developed to provide mental and physical well-being and other ecosystem services over and above those that were previously provided by a city’s private gardens and parks.

However, concepts like ecosystem services and green infrastructure are evaluated for their biological, ecological or technical functions, but are rarely related to well-being and health[54]. Similarly,most urban green infrastructure proposals are single purpose and do not consciously incorporate either biodiversity or public health. See for example,theCity of Vancouver Rain City Strategy[55]. This needs to change if the city of the future is to support human wellbeing and regional biodiversity.

Unless the dense megacity of the future becomes a biodiverse healing garden in itself,the negative effects on human wellbeing will be extensive. Conversely, by considering these two issues in urban planning and development, future cities can protect biodiversity and ecosystem services and increase human wellbeing.

3 The City as Garden

How will UGS replace the loss of private gardens on denser cities? POS includes parks,playgrounds, natural areas, municipal gardens,civic squares and school grounds within the public realm[28]. UGS describes all vegetated areas in cities,including private gardens, parks, golf courses, and street trees[56]. This is an important distinction as biodiversity, the ecosystems services it is related to and the health and wellness benefits of contact with nature occur in all UGS but not all POS. For this reason, achieving wellness and biodiversity in urban regions should concentrate on total UGS rather than POS. This means considering public and private open space in concert. Researchers report that accessible green spaces are usually higher in affluent neighbourhoods[57]. For the benefits of UGS to be equitable, its distribution will need to relate to urban densities across the metropolitan region.

3.1 Biodiversity and Psychological Restoration

It is important to understand that biodiversity and the mental restoration that comes from contact with nature are synergistic. Researchers who have examined the relationship between biodiversity and restoration report that biodiverse settings are more restorative (Fig. 3-5)[58-60]. This is in keeping with what is known as the biophilia hypothesis,which argues that people are innately predisposed to affiliate with nature[61]. Other researcher’s report that biological indicators of restoration increase in natural settings and that increasing biodiversity does not lower these effects[62]. Secondly, the presence of a diverse set of bird species in the landscape is a strong indicator of general biodiversity[63-64].Thus, raising avian biodiversity increases general biodiversity and is indicative of a more biophilic,and restorative landscape.

In terms of the restorative qualities of nature,it has been found that restoration and preference are closely linked. More naturalistic settings are preferred and those elements of a landscape that predict restoration predict preference and vice versa[65-66]. The quality of mystery i.e., the suggestion that moving forward will reveal more is a predictor of both landscape preference and the restorative experience[66-68]. In studies where levels of “greenness” were distinguished, restorative benefits were found more reliably or were greater for greener environments[69-70].

The more involved a person is in the landscape, the greater will be their mental processing of that landscape[71]and studies indicate that this higher involvement yields greater mental restoration[72]. In general, increasing the duration and frequency of contact with natural settings results in higher levels of restoration[73-74]so that the more time urban dwellers spend in their local UGS and the more often they do so, the greater will be the restorative effect they receive.

Researchers at the Institution of Landscape Planning Health and Recreation in Alnarp Sweden posit that a garden must be an outdoor room with walls and ceilings, that plants must be the dominant element, and that if it does not bring the message of life, and cyclical change it will not convey the feelings of peace, sensual stimulation and beauty.Further, they tell us that a healing garden is one that activates all the senses, not only sight but smell, taste and touch and that healing garden it is experienced over time as a series of rooms of different characters that make a whole where one is separated from the outside and feels safe[75].

These same researchers came to realize that parks that had many room characters attract more people than ones that had only one type of character and that certain types of characters were generally more attractive to people than others. (This is another example of the synergies between biodiversity and preference/restoration). Research shows that as habitat diversity i.e., the number of different types of habitat on a given site increase, biodiversity increases[53]. The researchers gave these eight types of room characters descriptive names (Tab. 1).

They found that the characters Serene, Space and Rich in Species appealed to many people and that The Common and The Pleasure Garden appeal to park visitors who are less stressed and wish to watch other people. Further, they reported that achieving these characters required natural areas,with many different kinds of plants and tall trees.

3.2 Strategies

Many researchers and designers have made recommendations for more biodiverse urban regions or more restorative urban environments and I encourage the interested reader to investigate these, as they are beyond the scope of this article[23,28,76-77]. From their recommendations, and my own investigations, a number of principles may be derived. While these are not comprehensive,they are widely applicable and based in empirical research. 1) Regional Networks: Relate action to scale. Many urban regions are biodiversity hot spots.To preserve this a regional ecological network should be planned and implemented. This should protect and connect the rare and representative biodiversity of the region. UGS should be added not as opportunity allows, but as part of an overall regional strategy to maintain a diversity of habitat types as this will support regional biodiversity[22,78].This strategy will produce a range of sizes and types of UGS that will allow people access to wilder areas, increase the types of landscape that people experience, accommodate a diverse set of UGS users and will enhance human wellbeing[59].2) Cues to Care: Many biodiverse landscapes may not conform to cultural norms. A range of ‘cues to care’ can be implemented to show that the landscape is intentional and is managed. This will aid in public acceptance[75,79]. 3) Make public green spaces a series of connected rooms of distinct but related character[75,80]. 4) From Policy to Design: Do not rely on only broad policies. Specific design directives will be needed, especially at smaller scales. For example, at the neighbourhood and site scale, provide a range of landscape characters for restoration and habitats for birds and insects –especially pollinators. These different habitats will increase biodiversity and will also provide a mix of landscape experiences[22,53]. 5) Nearby Nature: Make nature nearby and ubiquitous. It is often impossible to add large new UGS but adding street trees,or other plantings, to the views from hospitals,prisons, homes and work places is possible and will be important givers of restoration[81-84].6) Blend Public and Private: Break down the barriers between public and private making private open space for the public benefit[85]. Consider UGS as being the public and the private realm working together in concert. Make an interconnected network of diverse private gardens and incentivise wildlife and pollinator gardens. 7) Distribute green space equitably throughout the city[57]. 8) More Green Space: Make a higher percentage of urban open space, urban green space. Many cities have high open space requirements for fail to ensure that that space is green and publicly accessible. In large residential developments, make some part of the private open space, green space that is publicly accessible[7]. 9) Find small areas throughout the city and give them function and naturalness[27].10) Plant the Urban Forest: Planting large trees and forests that are vertically layered will increase biodiversity[86]. 11) Mix native and non-native plantings to benefit birds and pollinators. UGS plantings should be diverse and mix regionally appropriate non-native and native plants. This floristic diversity will support pollinators[22,87-88].12) The more deeply people are engaged in nature the greater their wellness benefits[22]. Plan, design and implement UGS that encourage people to actively engaged in stewardship, just as they have previously done in private gardens. This might mean more intensive roof top gardens in residential developments, home owners in multi-family residences caring for the communal landscape, more community gardens spread throughout the city, or school children participating in nest box programs for cavity nesting birds. 13) Make all new green infrastructure support multiple ecosystem services.Rain gardens and bioswales can be a “near nature”strategy to make the city more restorative as well as cleansing stormwater. 14) Concentrate UGS where people are concentrated e. g. airports, hospitals,schools workplaces and commuter corridors[23].

Notes:

① Retrieved from http://www.vroma.org/~hwalker/Pliny/PlinyNumbers.html.

② Retrieved from https://www.un.org/development/desa/en/news/population/2018-revision-of-world-urbanizationprospects.html.

③ After the City of Detroit, Michigan lost its biggest employers and tax base it declared bankruptcy in 2013 and much of the urban core became derelict. Today, many neighbourhoods are seeing a resurgence with former some building sites become urban green spaces. The ASLA award winning Lafayette Greens Community Garden by Kenneth Weikal Landscape Architecture occupies the site of the Lafayette Building in downtown Detroit which was demolished in 2010. The garden was donated to The Greening of Detroit by Compuware in 2014. As well as community food production, the gardens support community gathering and events, a children’s garden and pollinator habitat.

④ Retrieved from https://www.asla.org/sites/.

⑤ Retrieved from https://www.landscapeperformance.org.

Sources of Figures and Table:

Fig. 1 from https://www.asla.org/2012awards/073.html;Fig. 2 ? Charlotte Chen, Marco Leung, and Alwyn Rutherford; Fig. 3: Design and photos used with permission Murdoch Degreeff Inc. Landscape Architects; Fig. 4: Image Ted McGrath, used under creative commons licence;Fig. 5: Image by Ty, used under creative commons licence.Tab . 1 from reference[75].

(Editor / LIU Yuxia)