Hepatocellular injury and the mortality risk among patients with COVID-19: A retrospective cohort study

Ali Madian, Ahmed Eliwa, Hytham Abdalla, Haitham A Azeem Aly

Ali Madian, Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Department of Internal Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Al-Azhar University-Assiut, Assiut 71524, Egypt

Ahmed Eliwa, Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Department of Internal Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Al-Azhar University-Cairo, Cairo 11754, Egypt

Hytham Abdalla, Department of Chest Diseases, Faculty of Medicine, Al-Azhar University-Assiut, Assiut 71524, Egypt

Haitham A Azeem Aly,Department of Internal Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Al-Azhar University-Assiut, Assiut 71524, Egypt

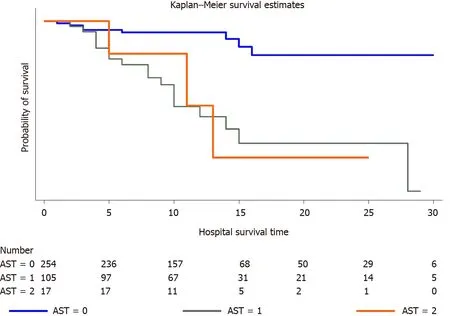

Abstract BACKGROUND Clearly, infection with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 is not limited to the lung but also affects other organs.We need predictive models to determine patients’ prognoses and to improve health care resource allocation during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic.While treating COVID-19, we observed differential outcome prediction weights for markers of hepatocellular injury among hospitalized patients.AIM To investigate the association between hepatocellular injury and all-cause inhospital mortality among patients with COVID-19.METHODS This multicentre study employed a retrospective cohort design.All adult patients admitted to Al-Azhar University Hospital, Assiut, Egypt and Abo Teeg General Hospital, Assiut, Egypt with confirmed COVID-19 from June 1, 2020, to July 30, 2020 were eligible.We categorized our cohort into three groups of (1) patients with COVID-19 presenting normal aminotransferase levels; (2) patients with COVID-19 presenting one-fold higher aminotransferase levels; and (3) patients with COVID-19 presenting two-fold higher aminotransferase levels.We analysed the association between elevated aminotransferase levels and all-cause in-hospital mortality.The survival analysis was performed using the Kaplan-Meier method and tested by log-rank analysis.RESULTS In total, 376 of 419 patients met the inclusion criteria, while 29 (8%) patients in our cohort died during the hospital stay.The median age was 40 years (range: 28-56 years), and 51% were males (n = 194).At admission, 54% of the study cohort had liver injury.The pattern of liver injury was hepatocellular injury with an aspartate aminotransferase (AST) predominance.Admission AST levels were independently associated with all-cause in-hospital mortality in the logistic regression analysis.A one-fold increase in serum AST levels among patients with COVID-19 led to an eleven-fold increase in in-hospital mortality (P < 0.001).Admission AST levels correlated with C-reactive protein (r = 0.2; P < 0.003) and serum ferritin (r = 0.2; P < 0.0002) levels.Admission alanine aminotransferase levels correlated with serum ferritin levels (r = 0.1; P < 0.04).Serum total bilirubin levels were independently associated with in-hospital mortality in the binary logistic regression analysis after adjusting for age and sex but lost its statistical significance in the fully adjusted model.Serum ferritin levels were significantly associated with in-hospital mortality (P < 0.01).The probability of survival was significantly different between the AST groups and showed the following order: a two-fold increase in AST levels > a one-fold increase in in AST levels > normal AST levels (P < 0.0001).CONCLUSION Liver injury with an AST-dominant pattern predicts the severity of COVID-19.Elevated serum ferritin levels are associated with fatal outcomes.

Key Words: COVID-19; Liver injury; Aspartate amino transferase; All-cause in-hospital mortality; Serum ferritin; SARS-CoV-2

INTRODUCTION

Globally, coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has a substantial impact on the healthcare system.Over time, clinicians have clearly determined that the infection caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) is not limited to the lung but also affects the nervous system, gastrointestinal tract and hepatobiliary system[1].

The entry of SARS-CoV-2 into target cells is facilitated by angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptors.ACE2 receptors are expressed at high levels in lung alveolar epithelial cells, vascular endothelium and epithelium of the small intestine[2].This pattern might explain the pathophysiology of gastrointestinal manifestations associated with COVID-19, such as vomiting and diarrhoea.Moreover, ACE2 receptors are expressed at high levels on cholangiocytes (60% of cells) and to a lesser extent on hepatocytes (3% of cells)[3].Therefore, the hepatobiliary system may be at increased risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection.The liver appears to be the second most affected organ after the lung[4].

In fact, many case series identified abnormal elevations in the levels of aminotransferases and hypoalbuminemia early and during the progression of COVID-19[5,6].However, substantial variability in the reported prevalence of liver injury among patients with COVID-19 was noted (14% to 50%)[3].Moreover, the clinical effect of de novo liver injury on the prognosis of patients with COVID-19 has not been investigated in detail.In addition, multiple clinical comorbidities that might confound liver injury-associated mortality should be studied[7].

Ideally, clinicians should be able to identify patient outcomes to improve health care resource allocation.

The aim of the present study was to investigate whether biomarkers of hepatocellular injury have prognostic value in predicting all-cause in-hospital mortality among patients with COVID-19.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This multicentre study employed a retrospective cohort design.The medical records of all consecutive adult patients admitted to Al-Azhar University Hospital, Assiut, Egypt and Abo Teeg General Hospital, Assiut, Egypt with confirmed COVID-19 from June 1, 2020, to July 30, 2020 were retrieved and analysed.Both hospitals were designated to treat patients with confirmed COVID-19 by the Egyptian Ministry of Health.The inclusion criteria were hospitalization and adult patients > 18-years-old with confirmed COVID-19 based on a positive nasopharyngeal swab for SARS-CoV-2.Exclusion criteria were non-hospitalized patients, pregnant females, patients with chronic liver disease (in accordance with institutional clinical guidelines, patients with elevated aminotransferase levels were screened for markers of viral hepatitis and markers of autoimmune hepatitis), patients who refused to participate in the study and patients with incomplete data.The institutional review board granted approval for the study protocol.

Exposure measurement

The exposure of interest was the serum levels of aminotransferases at the time of hospital admission.We measured the levels of aminotransferases within 24 h of hospital admission.Elevated aminotransferase levels were defined as either an increase in the levels of aspartate aminotransferase (AST) (> 40 U/L), alanine aminotransferase (ALT) (> 40 U/L) or both proteins compared with the upper limit of normal.We classified our cohort into three groups based on serum levels of aminotransferases: (1) Patients with COVID-19 presenting normal aminotransferase levels; (2) Patients with COVID-19 presenting a one-fold increase in aminotransferase levels; and (3) Patients with COVID-19 presenting a two-fold increase in aminotransferase levels.

Covariates

In every enrolled participant, covariates analysed included baseline patient characteristics, such as age, sex and smoking status, comorbidities, such as diabetes mellitus, hypertension, ischaemic heart disease, chronic kidney disease and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, Deyo-Charlson index, obesity and initial laboratory investigations and AST/ALT, serum total bilirubin, serum albumin, blood urea, serum creatinine, Creactive protein (CRP), creatine kinase (CK), serum ferritin and D-dimer levels.

Outcome measurement

The predefined primary outcome of the study was all-cause in-hospital mortality.The secondary outcome was the length of the hospital stay.The vital status of the study participants was obtained from hospital records.The censoring date for follow-up of the outcome was August 15, 2020.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were presented as medians and interquartile ranges, and categorical variables were presented as absolute numbers and percentages.For the statistical analysis of group differences, we performed unadjusted binary logistic regression analyses.We utilized a stepwise analysis adjusted for sex and age as well as for clinically relevant confounders listed above to investigate confounding factors.Spearman’s correlation coefficients were calculated to analyse the relationships between variables.AllPvalues presented were two-tailed; values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.We used Stata Software (Stata Statistical Software: Release 16.College Station, TX: Stata Corp LP) for data visualization and analysis.

RESULTS

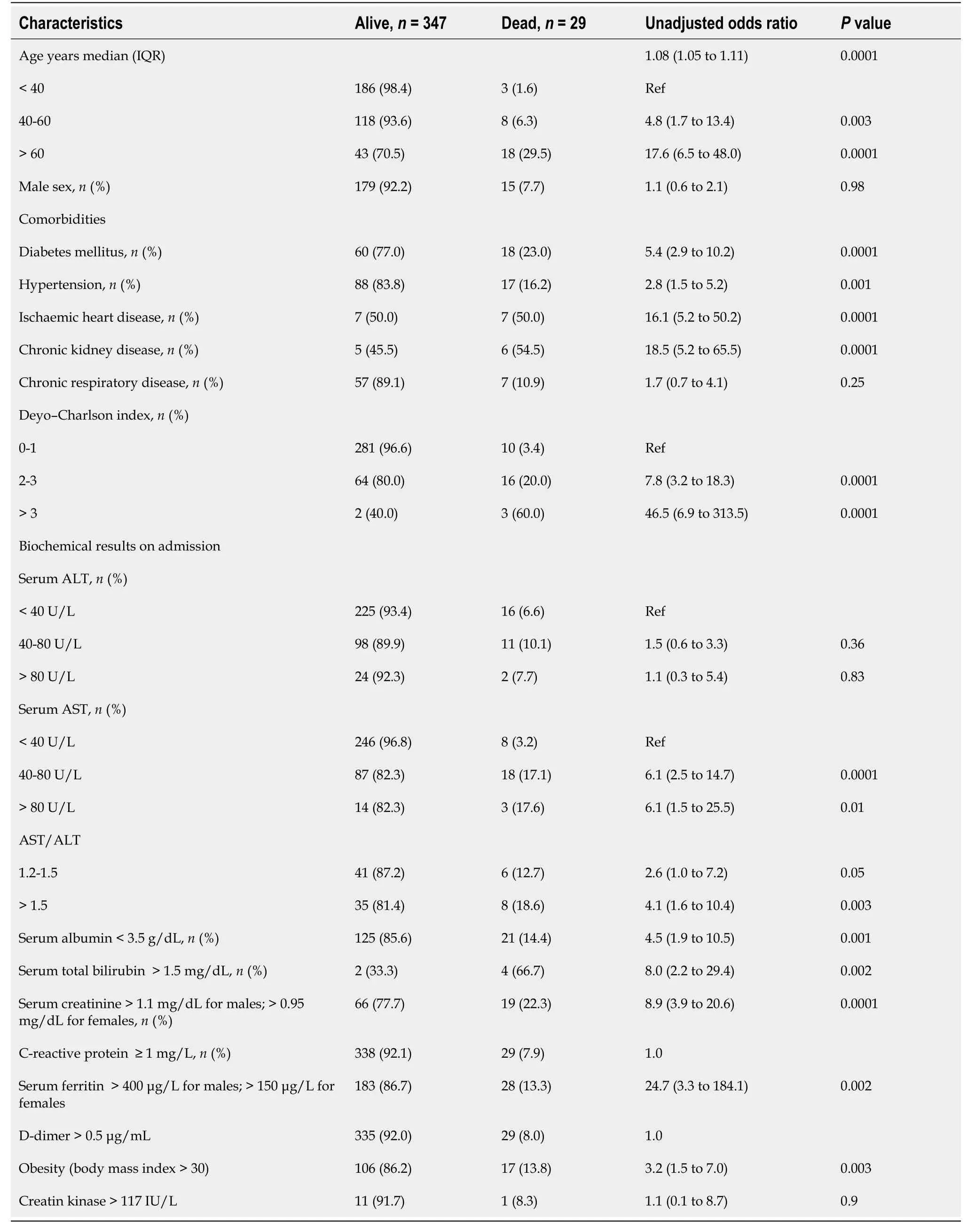

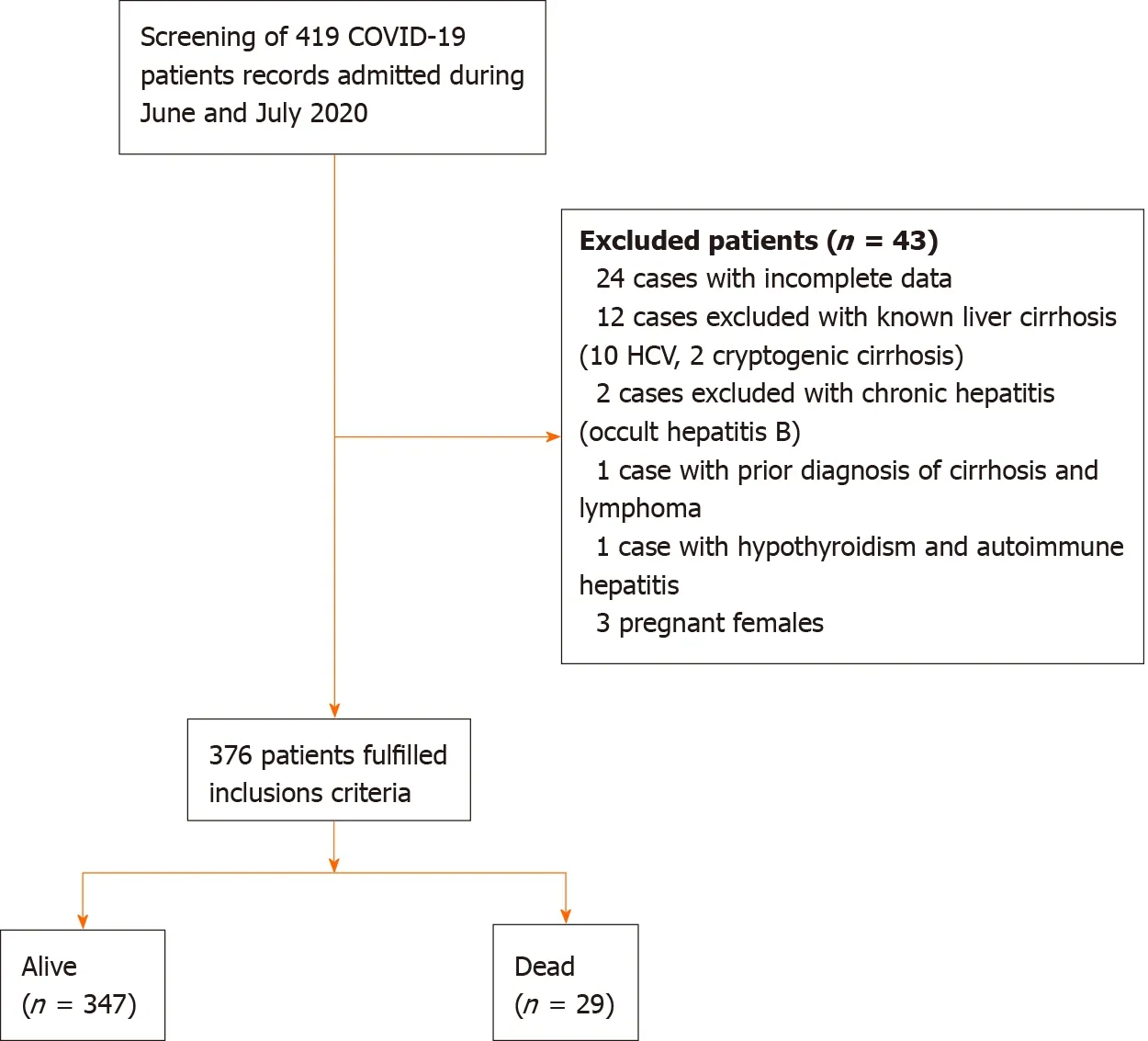

In total, 376 of 419 patients met the inclusion criteria, and 8% of these patients died during the hospital stay (n= 29) (Figure 1).The median age was 40 years (range: 28-56 years), and 51% were males (n= 194) (Table 1).Patients in our study cohort were stratified according to all-cause in-hospital mortality into alive and dead groups, and their characteristics are presented in Table 1.

Predictors of the outcome

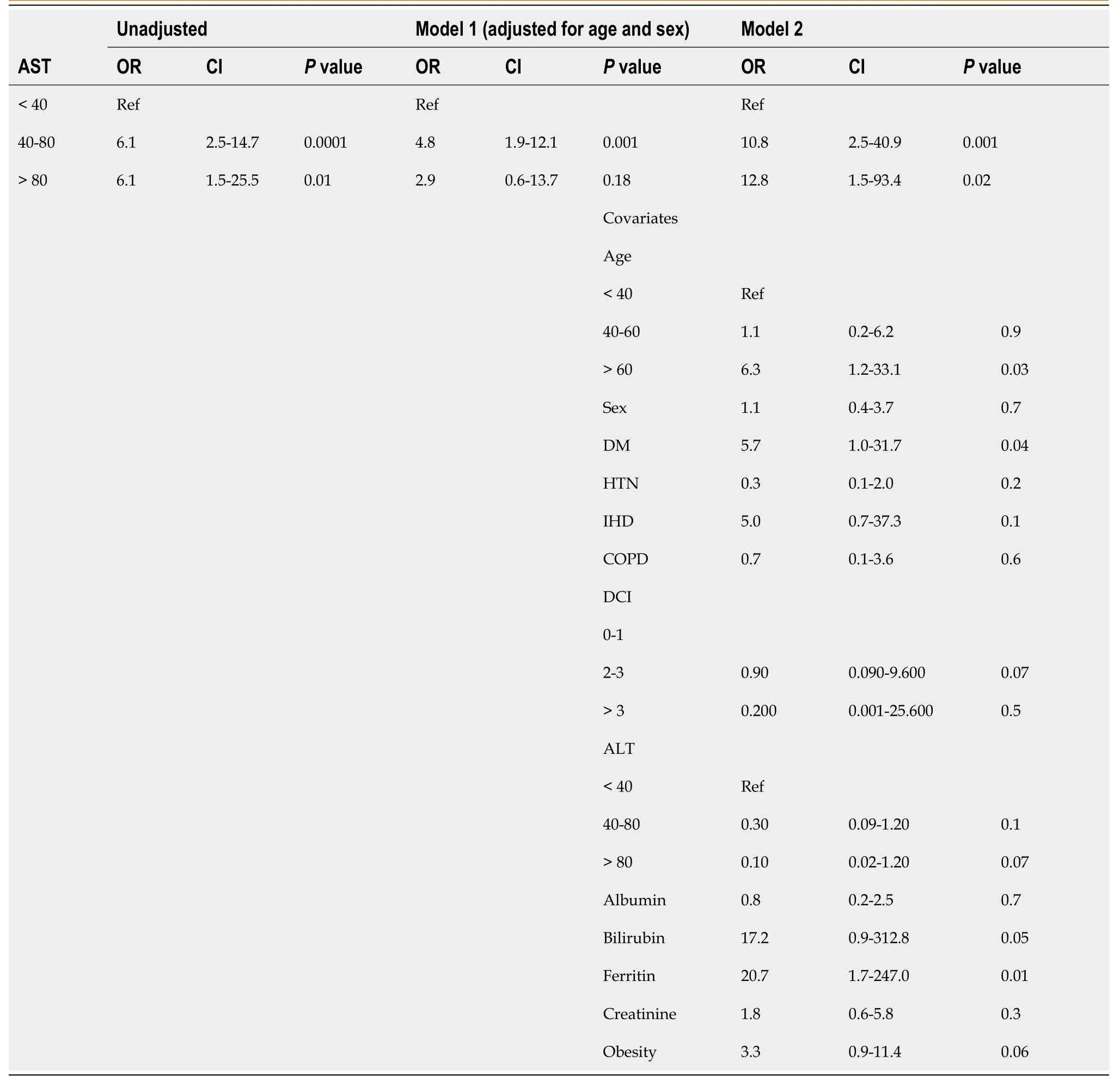

Regression analysis:(1) Unadjusted analysis.The unadjusted binary logistic regression analysis revealed that age, diabetes, hypertension, ischaemic heart disease, chronic kidney disease, obesity and Deyo-Charlson index were significant clinical factors associated with all-cause in-hospital mortality.In addition, AST, serum total bilirubin, serum albumin, serum creatinine and serum ferritin levels were the laboratory biomarkers significantly associated with all-cause in-hospital mortality.However, sex, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and ALT, CRP, CK and D-dimer levels were not associated with all-cause in-hospital mortality; and (2) Adjusted analysis.The AST level at admission was the only biomarker of liver injury that was independently associated with all-cause in-hospital mortality in the unadjusted binary logistic regression analysis and model 1 adjusted for age and sex (Table 2).In addition, in model 2, after stepwise adjustment for several clinically relevant confounders, AST levels were still significantly associated with all-cause in-hospital mortality.Serum total bilirubin levels were independently associated with in-hospital mortality in the binary logistic regression after adjusting for age and sex but lost its statistical significance in the fully adjusted model.

Association of aminotransferase levels with CK levels

CK was studied as a marker of muscle injury.At admission, AST levels did not correlate with CK levels (r= -0.006;P= 0.9).In addition, admission ALT levels did not correlate with CK levels (r= -0.02;P= 0.6).

Association of aminotransferase levels with inflammatory markers

Serum ferritin and CRP levels were examined as markers of inflammation.At admission, AST levels correlated with CRP (r= 0.2;P< 0.003) and serum ferritin (r= 0.2;P< 0.0002) levels.Admission ALT levels correlated with serum ferritin levels (r= 0.1;P< 0.04) but not with CRP (r= 0.09;P= 0.08).

Association of serum ferritin levels with inflammatory markers

Admission serum ferritin levels correlated with CRP levels (r= 0.4;P< 0.0001).

Among our cohort, we identified 6 patients with biphasic hyperbilirubinemia.ALT levels correlated with serum total bilirubin levels (r= 0.2;P< 0.003).Therefore, hyperbilirubinemia was due to liver injury and not haemolysis.

Probability of survival

The probability of survival was significantly different between AST groups.As shown in the Kaplan-Meier curves (Figure 2), the probability of mortality progressively increased as the serum level of AST increased in the following order: two-fold increase in AST levels > a one-fold increase in AST levels > normal AST levels.

DISCUSSION

Numerous studies have reported the effect of liver injury on the outcomes of hospitalized patients with COVID-19[8].However, a growing concern is that many demographic, clinical and laboratory markers might confound this association.These potential confounders should be recognized, and their effects on the associationbetween biomarkers of hepatocellular injury and patient outcomes should be investigated.In fact, while treating COVID-19, we observed differential outcome prediction weights for markers of hepatocellular injury among hospitalized patients.

Table 1 Baseline demographic, clinical and laboratory characteristics of alive and dead groups

Table 2 Odds ratios of liver injury associated mortality and 95% confidence intervals by aspartate aminotransferase categories

At admission, 54.0% of patients in our cohort had liver injury.AST levels were elevated in 32.5% (n= 122), ALT levels were elevated in 36.0% (n= 135), and both ALT and AST levels were increased in 23.0% (n= 87).Among nonsurvivors, the pattern of liver injury was hepatocellular injury with an AST predominance.Both ALT and AST levels were elevated in 45.0% of nonsurvivors.An isolated elevation of AST levels was detected in 31.0% of nonsurvivors, while an isolated elevation of ALT levels was detected in 3.0%.Notably, 48.0% of nonsurvivors presented an AST/ALT ratio > 1.2, and serum total bilirubin levels were increased in 1.6% of patients in our study cohort.

We observed an obvious increase in mortality among patients with COVID-19 presenting elevated serum AST levels at the time of admission.A one-fold increase in the serum level of AST increased the odds of in-hospital mortality eleven-fold compared to those with normal AST levels at admission.Moreover, a two-fold increase in serum AST levels predicated a thirteen-fold increase in mortality.We can thus postulate from the findings of the present study that elevated AST levels at admission are a harbinger of a worse prognosis for patients with COVID-19.On the other hand, serum ALT, bilirubin and albumin levels did not alter mortality after correction for age, sex and other relevant clinical factors.Our findings are consistent with recent reports investigating progressive liver injury and the risk of mortality among patients with COVID-19 where AST levels but not ALT levels at admission were a strong predictor of mortality[9-11].

Figure 1 Flowchart of studied cohort.

Figure 2 Kaplan–Meier curves.

In our cohort, AST levels did not correlate with the levels of CK, a marker of muscle injury, at admission.Moreover, AST levels correlated moderately with inflammatory markers at admission.Based on these findings, liver injury in patients with COVID-19 may be related to the proinflammatory state associated with cytokine release.

In healthy individuals, plasma levels of ALT and AST represent the balance between normal turnover of hepatocytes by apoptosis and the clearance rates of these enzymes from hepatic sinusoids.Normally, ALT is present in the cytoplasm of hepatocytes, whereas AST is present in the cytoplasm and mitochondria of hepatocytes.Although the ratio of hepatic AST/ALT is 2.5:1, the serum levels of AST and ALT are similar after hepatocyte turnover because the clearance rate of AST is two times faster than the clearance rate of ALT[12,13].

In individuals with hepatocellular injury, serum levels of AST and ALT reflect the time course of hepatic injury and prognosis of hepatic insult.Early hepatocyte injury results in the release of cytosolic AST and ALT.If hepatocyte injury is severe, mitochondrial damage will result in increased release of mitochondrial AST in serum.Therefore, the predominant increase in the admission AST levels in our cohort might reflect early and severe hepatocyte injury.Furthermore, SARS-CoV-2 may induce endothelial cell injury in the hepatic microcirculation and promote portal or sinusoidal microthrombosis.In individuals with ischaemic liver injury (due to microthrombosis), serum AST levels peak before ALT levels, a pattern that was observed in our cohort[9,11,13].

In practice, an isolated and predominant elevation of AST levels indicates a nonhepatic source of AST,e.g., muscle, and haemolysis.

Myositis results in increased levels of AST and, to a lesser extent, ALT; however, the increased serum levels of muscular aminotransferases should be associated with increased serum levels of CK.In our cohort, no significant correlation between AST and CK levels at admission was observed.This finding suggests true hepatic injury as the main source of elevated AST levels.

Haemolysis results in increased levels of AST and unconjugated bilirubin.In our cohort, we identified 6 patients with biphasic hyperbilirubinemia.ALT levels correlated with serum total bilirubin levels.Therefore, hyperbilirubinemia was due to liver injury and not haemolysis.

Among our cohort, 33.0% of patients were obese, perhaps with underdiagnosed nonalcoholic fatty liver disease.In addition, 20.0% of patients in our cohort were diagnosed with diabetes.Both diabetes mellitus and obesity increase serum levels of AST and ALT, but this change is more prominent for ALT than for AST[14].

The mechanism of liver injury among patients with COVID-19 is unclear and possibly multifactorial.The entry of SARS-CoV-2 into hepatocytes and cholangiocytes is mediated by ACE2 receptors.Liver biopsies obtained from deceased patients diagnosed with COVID-19 revealed focal degeneration and necrosis.In addition, SARS-CoV-2 particles were detected in hepatocytes[4].Focal hepatic degeneration and necrosis may be due to the direct cytopathic effect of viral entry or could be an immune-mediated process.Entry of SARS-CoV-2 into hepatocytes triggers an innate and adaptive immune response that results in clearing of virus-infected cells.However, if the mounted immune response is exaggerated and uncontrolled, this aberrant immune response may contribute to the development of a cytokine storm and multisystem dysfunction[4,15].Moreover, hyperinflammatory syndrome can induce disseminated intravascular coagulation with ischaemic hepatocellular injury by microvascular thrombosis in the hepatic microcirculation.In addition, direct endothelial cell damage in the hepatic microcirculation induced by SARS-CoV-2 may promote microvascular thrombosis and ischaemic liver injury[11].

In addition, our findings indicated that an age > 60 years, diabetes mellitus and increased serum ferritin levels were independent strong predictors of mortality among patients with COVID-19 presenting liver injury.These observations are consistent with recent studies[10].

Our study provides evidence that serum ferritin levels were associated with allcause in-hospital mortality.Of our cohort, 56.0% of patients presented elevated serum ferritin levels.Moreover, 97.0% of nonsurvivors had elevated serum ferritin levels.In addition, logistic regression analysis showed that the serum ferritin level was an independent risk biomarker for in-hospital mortality among patients with COVID-19.Furthermore, admission serum ferritin levels correlated with CRP levels.These results suggest that elevated serum ferritin levels at admission may reflect disease severity.Our findings are consistent with a recent report confirming that increased ferritin levels are associated with in-hospital mortality in patients with COVID-19[16].

Inflammatory cytokines stimulate hepatocytes and macrophages to release ferritin, which plays a vital role in many autoimmune diseases and inflammatory disorders.A vicious loop exists between ferritin and inflammatory cytokines,i.e.activated hepatocytes and macrophages release ferritin, which in turn stimulates the production of various inflammatory cytokines.Serum ferritin is an inflammatory cytokine that indirectly stimulates proinflammatory pathways through the activation of the transcription factor nuclear factor kappa-B.Moreover, the heavy subunit of ferritin directly increases the mRNA expression of many inflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin-1, interleukin-6, tumour necrosis factor and NOD-like receptor 3, indicating the proinflammatory properties of ferritin[16,17].

Patients with diabetes have elevated serum ferritin levels, and these patients are at increased risk of serious complications from COVID-19.Therefore, ferritin may be a key mediator of immune dysregulation that contributes to the cytokine storm in patients with diabetes mellitus and COVID-19[16,17].

Limitations

This retrospective study revealed an association between AST levels and mortality in patients with COVID-19 but did not reveal causality.Numerous medications and clinical and biological conditions injure hepatocytes but were only partially considered in the regression analysis.We used liver enzyme level at the time of admission for group categorization without knowing whether they were episodic or progressive changes.We did not consider concurrent medication use, such as angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers, in our analysis.Underdiagnosed nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and occult consumption of alcohol were not considered.

CONCLUSION

Our study revealed that liver injury is highly prevalent among patients with COVID-19 at admission.Liver injury with an AST-dominant pattern can be used to predict the severity of COVID-19.This study confirmed an elevated level of ferritin in patients with COVID-19.Admission serum ferritin levels are associated with fatal outcomes.Meticulous monitoring is highly recommended for patients with COVID-19 presenting AST-dominant hepatocellular injury, especially those older than 60 years, those with elevated levels of ferritin and those with diabetes mellitus.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

Research background

Clearly, infection with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 is not limited to the lung but also affects other organs.

Research motivation

Predictive models are needed to determine patients’ prognoses and to improve health care resource allocation during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic.

Research objectives

To investigate whether biomarkers of hepatocellular injury at admission have prognostic value in predicting all-cause in-hospital mortality in patients with COVID-19.

Research methods

A retrospective cohort study was conducted on 376 consecutive adult patients admitted to Al-Azhar University Hospital, Assiut, Egypt and Abo Teeg General Hospital, Assiut, Egypt with confirmed COVID-19 from June 1, 2020 to July 30, 2020.

Research results

High-risk populations, especially patients aged ≥ 60 years, patients with aspartate aminotransferase (AST)-dominant liver injury or those with diabetes, should be intensively monitored.Admission serum AST and serum ferritin levels have the strongest association with the prognosis of patients with COVID-19 and can be used to monitor patients with COVID-19 at risk of liver injury.

Research conclusions

Liver injury with an AST-dominant pattern can predict the severity of COVID-19.This study confirmed an elevated level of ferritin in patients with COVID-19.Elevated serum ferritin levels are associated with in-hospital mortality.

Research perspectives

Meticulous monitoring is highly recommended for patients with COVID-19 presenting AST-dominant hepatocellular injury, especially those older than 60 years, patients with elevated serum ferritin levels or those with diabetes mellitus.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We appreciate the effort of all medical staff and technicians who agreed to participate in this study.

World Journal of Hepatology2021年8期

World Journal of Hepatology2021年8期

- World Journal of Hepatology的其它文章

- Solid pseudopapillary neoplasm of the pancreas

- Non-invasive tests for predicting liver outcomes in chronic hepatitis C patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis

- Clostridioides difficile infection in liver cirrhosis patients: A population-based study in United States

- Association of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and COVID-19: A literature review of current evidence

- Therapeutic plasma exchange in liver failure

- Current state of endohepatology: Diagnosis and treatment of portal hypertension and its complications with endoscopic ultrasound