Circulatory and hepatic failure at admission predicts mortality of severe scrub typhus patients: A prospective cohort study

Ashok Kumar Pannu, Atul Saroch, Saurabh Chandrabhan Sharda, Manoj Kumar Debnath, Manisha Biswal,Navneet Sharma?

1Department of Internal Medicine, Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education and Research, Chandigarh, India

2Department of Medical Microbiology, Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education and Research, Chandigarh, India

ABSTRACT

KEYWORDS: Scrub typhus; Orientia tsutsugamushi; Organ failure; Mortality; Prognosis

1. Introduction

Acute febrile illnesses (AFIs) are common indications for emergency admissions and have various causes in different geographic regions and seasons. In tropical or subtropical areas(like Southeast Asia), they usually constitute leptospirosis, enteric fever, malaria, dengue, and scrub typhus during the rainy or post rainy season[1]. Early differentiation among these tropical AFIs is challenging, given the overlapping clinical and laboratory features and organ dysfunction with any combination of respiratory failure, acute kidney injury, hepatic dysfunction, encephalopathy,circulatory shock, and coagulative dysfunction[1,2].

Scrub typhus, a rickettsial infection, is caused by Orientia (O.)tsutsugamushi and transmitted by the bite of the larvae (‘chiggers’)of trombiculid mites. The primary reservoirs are vector mites and rodents, mainly field rodents. This zoonotic infection is historically considered endemic in the geographic area termed ‘tsutsugamushi triangle’ extending from eastern Russia, west to Pakistan and south to northern Australia. But recently, it has been increasingly identified outside this region. An estimated a million cases occur per year globally[3-10]. The infection typically manifests as an AFI with eschar, rash, hepatosplenomegaly, or thrombocytopenia; however, it may rapidly progress to life-threatening organ failure with 10%-15%mortality in severe cases[2,6-12].

Knowledge of organ dysfunction and illness severity in an AFI is critical in the emergency room for the early institution of empirical therapy and limited resources allocation. We carried out this study to document the spectrum and outcome of severe scrub typhus and to identify the prognostic implication of at-admission organ failure for hospital mortality.

2. Subjects and methods

2.1. Study oversight

This is a prospective observational cohort study of patients aged 13 years and above with severe scrub typhus admitted at the medical emergency of PGIMER, Chandigarh, India, from July 2017 to October 2020. This tertiary care centre covers a large population of adjoining geographic regions of north India, which are considered endemic of scrub typhus. We received institutional ethics committee approval (IEC-11/2017-746) and written informed consent from study participants.

2.2. Study definitions

Scrub typhus was diagnosed with typical clinical presentations(AFI with eschar or skin rash, dyspnea, hepatosplenomegaly,or thrombocytopenia) and microbiological confirmation of O.tsutsugamushi infection with enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay(ELISA) IgM antibodies or polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing of blood or eschar tissue.

Organ failure in scrub typhus was defined with Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score of ≥2 points (on a scale of 0 to 4 for each of six organ systems, aggregated score range 0 to 24, with higher scores indicating more severe organ dysfunction); i.e., the ratio of the arterial partial pressure of oxygen and the fraction of inspired oxygen <300 mmHg (pulmonary), serum creatinine ≥2 mg/dL (renal),serum bilirubin ≥2 mg/dL (hepatic), Glasgow coma scale score ≤12(cerebral), and hypotension requiring vasopressor support (circulatory);however, ≥3 points for coagulative (platelets <50 000 per mm)because thrombocytopenia is usual in scrub typhus[13]. The presence of any organ failure within one day of admission was considered as severe disease.

2.3. Laboratory confirmation

IgM ELISA was performed using commercially available kit Scrub Typhus Detect (InBios International), which is based on recombinant 56 kD type-specific antigens of the Karp, Kato, Gilliam, and TA716 strains of O. tsutsugamushi; the cut-off optical density of 0.468 indicating positivity as the manufacturer’s recommendation. For PCR, DNA extraction from the blood or eschar tissue was carried out by QIAamp, DNA Mini Kit (QIAGEN, Germany) method, and it was amplified using primer pair for the gene 56-kDa antigen of the Gilliam strain. Testing for other AFIs such as dengue (NS1 antigen,IgM and IgG ELISA), malaria (rapid diagnostic kit, malaria antigen,peripheral smear), leptospirosis (IgM ELISA, microagglutination test), and enteric fever (blood culture, Widal), and analysis (including culture) of urine or other body fluids were performed as appropriate to exclude alternate infectious etiologies.

2.4. Patient management and outcome

A comprehensive history taking and physical examination were carried out in all patients. A particular emphasis on finding the pathognomonic eschar was made, including showing the patients a photograph of eschar and asking if they had a similar skin lesion because the chiggers typically bite in moist parts like the perineum, genitalia, or breast folds that are often covered and overlooked. Hepatosplenomegaly was confirmed with abdominal ultrasonography. Basic laboratory investigations on admission included complete blood count, renal function tests,serum electrolytes, liver function tests, arterial blood gas analysis,electrocardiogram, chest radiograph, and abdominal ultrasound.

The patients were managed following standard ‘Surviving Sepsis Campaign Guideline’ using anti-rickettsial antibiotics, e.g.,doxycycline and/or azithromycin[14,15]. Sepsis prognostic scoring systems, SOFA, and quick SOFA (qSOFA) were calculated on admission in all cases[13]. qSOFA comprises systolic blood pressure≤100 mm Hg, respiratory rate ≥22 breaths per min, and Glasgow coma scale score <15, with ≥2 criteria (i.e., positive q-SOFA)indicating greater infection severity[13]. The patients were admitted to a high dependency emergency ward or intensive care unit according to the bed availability and followed till hospital discharge or death.Outcomes were measured as in-hospital mortality, length of hospital stay, and organ support requirement with invasive mechanical ventilation for any indication, renal replacement therapy for renal failure, or vasopressors for shock during hospitalization.

2.5. Statistical analysis

The analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics software,version 25.0 (IBM) for Mac. Categorical variables were expressed as numbers and percentages, and continuous variables as median with interquartile range (Q1, Q3) or mean with standard deviation(SD). The variables were compared using the Chi-square test,Student’s t-test, or the nonparametric Mann-Whitney-Wilcoxon test. Multivariate logistic regression was performed to ascertain the effects of organ dysfunction on the likelihood of hospital mortality,and odds ratio (OR) and corresponding 95% confidence interval(CI) were calculated. All tests of significance were two-tailed, and a P-value <0.05 indicated a statistical significance.

3. Results

A total of 126 adult patients with severe scrub typhus were included from adjoining areas such as Haryana (n=38, 30.16%), Himachal Pradesh (n=35, 27.78%), Punjab (n=34, 26.98%), Chandigarh (n=8,6.35%), Uttarakhand (n=5, 3.97%), Uttar Pradesh (n=4, 3.17%),Madhya Pradesh (n=1, 0.79%), and Jammu and Kashmir (n=1,0.79%). The microbiological diagnosis was established by IgM ELISA (n=120, 95.24%), blood PCR (n=22, 17.46%), or eschar PCR(n=14, 11.11%). The patients were admitted in monsoon and postmonsoon season, i.e., July (n=5, 3.97%), August (n=39, 30.95%),September (n=43, 34.13%), October (n=27, 21.43%), and November(n=12, 9.52%).

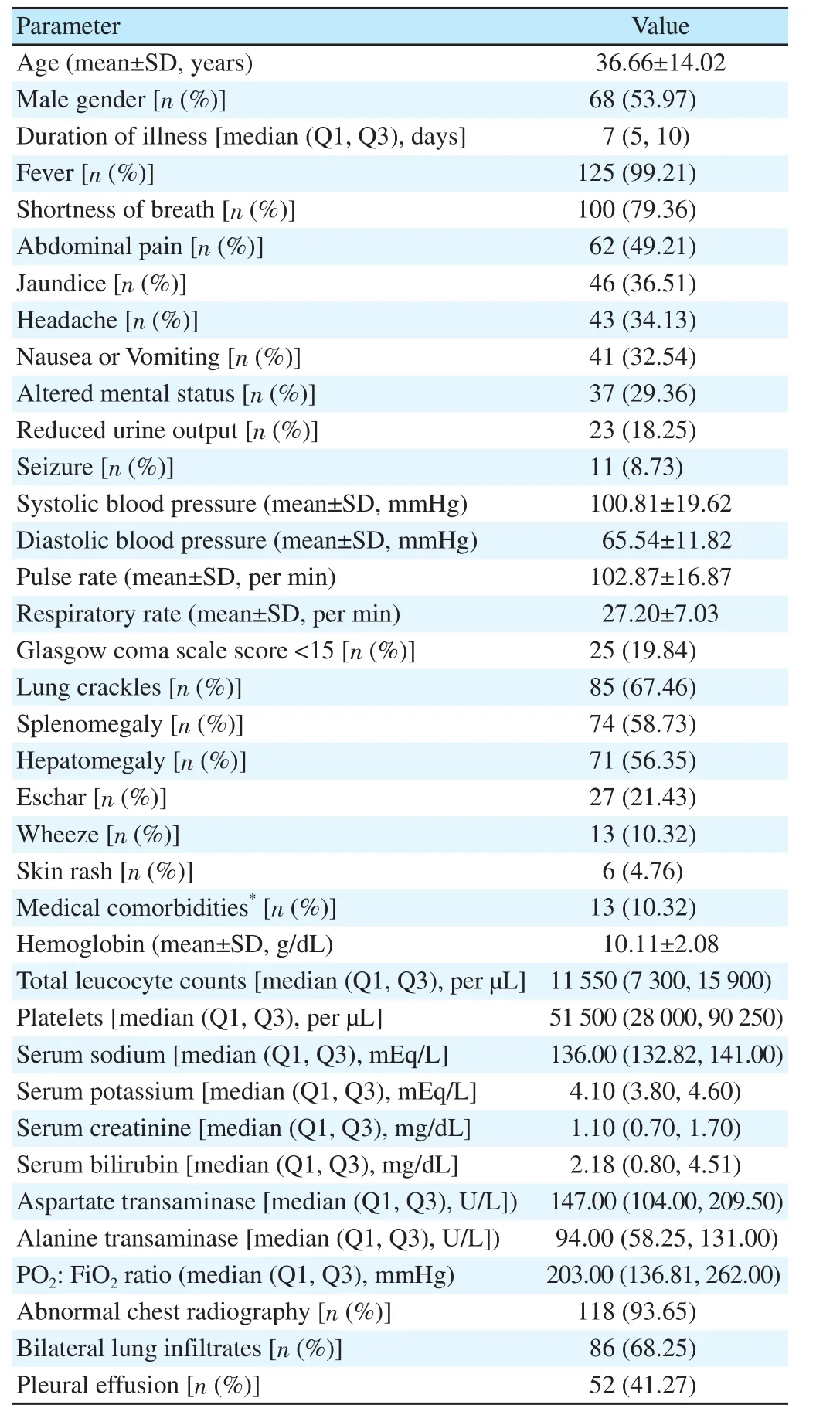

Table 1 showed the demographic, clinical, and laboratory characteristics of the study patients. The median (Q1, Q3) duration of illness before hospital presentation was 7 (5, 10) days, with fever(99.21%) and dyspnea (79.36%) being the most common complaints.Characteristic physical findings were lung crackles (67.46%),splenomegaly (58.73%), and hepatomegaly (56.35%). Eschar was evident only in 21.43% patients, even when it was explicitly looked at. Initial chest radiographs were frequently abnormal (n=118,93.65%), with bilateral lung infiltrates (n=86, 68.25%) more common than unilateral focal infiltrates (n=29, 23.01%), and pleural effusion (n=52, 41.27%) of mild (n=41, 78.85%) or moderate (n=11,21.15%) amount.

Table 1. Demographic and baseline characteristics of patients with severe scrub typhus (n=126).

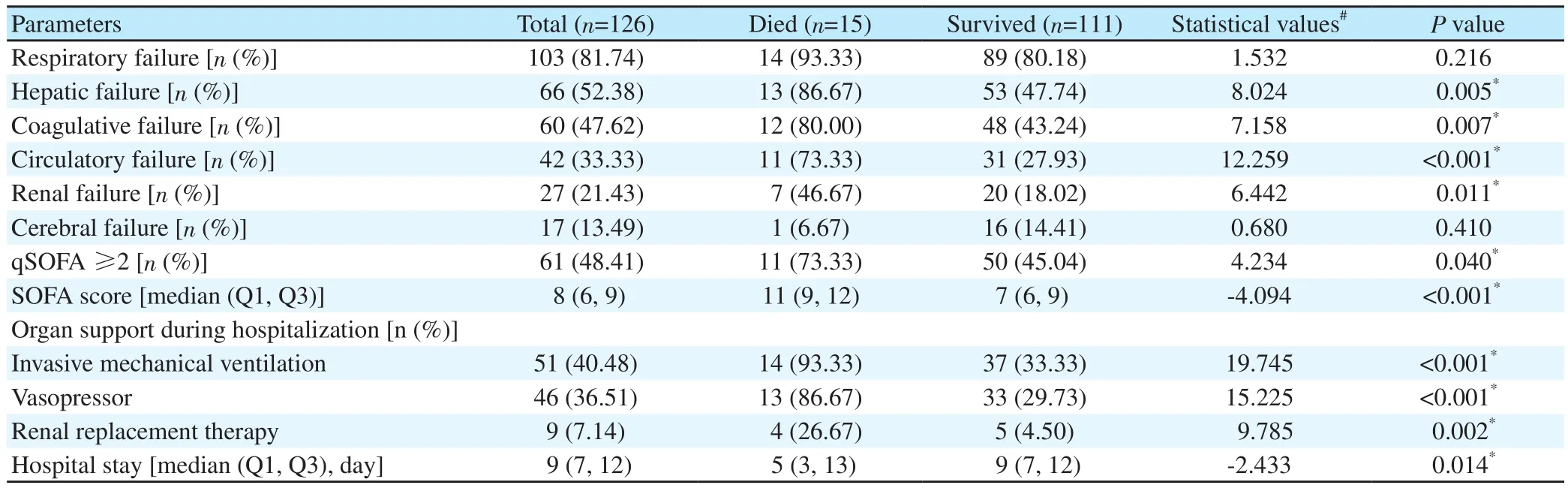

Table 2. Organ dysfunction at admission and outcomes in patients with severe scrub typhus stratified by survival.

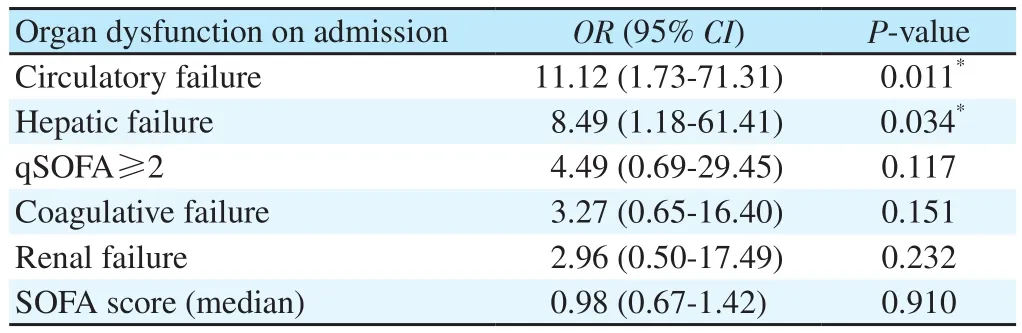

The most common organ failure at presentation was pulmonary(81.75%), followed by hepatic (52.38%), coagulative (47.62%),circulatory (33.33%), renal (21.43%), and cerebral (13.49%). The median (Q1, Q3) SOFA score of the study patients was 8 (6, 9),and qSOFA scores of 0, 1, 2, and 3 were seen in 7.94%, 43.65%,38.09%, and 10.32% patients. The overall in-hospital mortality was 11.90%. Univariate survival analysis of organ dysfunction variables on admission indicated that a significant poor prognosis for hospital mortality was associated with circulatory, hepatic, coagulative, and renal failures, positive q-SOFA, and high SOFA score (Table 2).Among these, circulatory and hepatic failures independently predicted mortality on logistic regression analysis (OR 11.12, 95% CI 1.73-71.31 and OR 8.49, 95% CI 1.18-61.41, respectively) (Table 3).

Table 3. Multivariate logistic regression analysis of organ dysfunction and hospital mortality.

Organ supports with invasive ventilation (n=51, 40.48%),vasopressors (n=46, 36.51%), and renal replacement therapy (n=9,7.14%, hemodialysis in seven, and sustained low-efficiency dialysis and peritoneal dialysis in each one) were frequently required during the hospital stay and significantly more for the patients with an unfavorable outcome. The median (Q1, Q3) duration of hospital stay was 9 (7, 12) days.

4. Discussion

In this case series of severe scrub typhus during four monsoon seasons in north India, the majority presented with respiratory failure, about half also had hepatic or coagulative failure, and invasive ventilatory support was frequently required. Hospital mortality was about 12% and strongly associated with circulatory or hepatic failure on admission.

About two-thirds of the study population were from geographic regions outside the sub-Himalayan belt (i.e., Himachal Pradesh,Uttarakhand), which confirms the geographic expansion of the infection in north India. This progression may be due to deforestation or microclimate changes[11,12,16]. These findings are critically important because physicians in the areas outside of endemicity may not be familiar with the varied presentations and organ involvement of the infection, resulting in misdiagnosis or delayed diagnosis.

Respiratory failure remained the predominant organ complain on hospitalization and was presented in at least 4 out of 5 severe cases.Pulmonary features such as dyspnea, lung crackles, and bilateral radiographic opacities were typical and consistent with other case series[2,9-12,17-19]. Invasive ventilation was frequently needed in the study patients. Relative frequencies of other organ dysfunctions in this study correlate with previous reports from this geographic region;however, because the study cohort represents the severe end of scrub typhus, we cannot describe the infection’s full spectrum[2,9-12,15-19].

Not surprisingly, shock requiring vasopressors remains the most important prognostic marker in scrub typhus[2,12,19]. Hepatic failure was the other strong predictor of the outcome in our study. Because small-vessel vasculitis-like systemic involvement is the infection’s primary pathogenesis, hepatic dysfunction is thought to be caused by the sinusoidal endothelial cellular injury[20,21]. However, we hypothesized that acquired hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis,an increasingly being reported severe hyperinflammatory syndrome in scrub typhus, might also be a contributing factor, in which liver dysfunction is frequent[22,23]. Subsequent studies should evaluate the pathogenesis of individual organ injury to initiating appropriate targeted therapy. High SOFA and qSOFA scores were not independent predictors of mortality in this study, not as shown by our center’s previous small series[24].

In this study, the mortality of 11.90% reflects a gradually improving survival trend in north India compared to previous series (not restricted to severe cases): 17.27% in 2004, 14.28% in 2006, and 13.60% in 2014[9,12,25]. The potential explanations are increasing clinical awareness, empirical initiation of doxycycline or azithromycin for AFI or severe acute respiratory infection, and progress in intensive care and sepsis management.

Given a single-center study, the catchment population’s composition and laboratory resources limit the results’ generalisability. PCR was not done in all patients because it was not available throughout the study period. Because organ-specific imaging and relevant laboratory investigations were not performed in all cases, the spectrum of some complications such as myocarditis, encephalitis and hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis could not be described.

The prognostic implication of organ failures in scrub typhus for hospital mortality garnered from this study is easy to identify on admission, therefore, useful to make clinical decisions in the medical emergency. Pulmonary dysfunction remains the most common complication; however, circulatory or hepatic failure on admission is a strong predictor of death. Given high morbidity and mortality,the infection’s progression outside of previously identified endemic areas is striking.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Miss Priyanka Sharma (research assistant) for her help in data collection and analysis.

Authors’ contributions

All the authors vouch for the accuracy and completeness of the data. A.K.P. and N.S. developed the theoretical formalism. A.K.P.analyzed the data and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All the authors were involved in the management of the study patients. N.S.supervised the project.

Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Medicine

2021年5期

Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Medicine

2021年5期

- Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Medicine的其它文章

- Perceived susceptibility, severity, and reinfection of COVID-19 may influence vaccine acceptance-Authors' reply

- Perceived susceptibility, severity, and reinfection of COVID-19 may influence vaccine acceptance

- Successful containment of a COVID-19 outbreak in Bach Mai Hospital by prompt and decisive responses

- S gene drop-out predicts super spreader H69del/V70del mutated SARS-CoV-2 virus

- Extensively drug-resistant Salmonella typhi causing rib osteomyelitis: A case report

- Circulation of Brucellaceae, Anaplasma and Ehrlichia spp. in borderline of Iran,Azerbaijan, and Armenia