包容性設計:超越無障礙

凱瑟琳·霍韋爾,埃莉·托馬斯/Catherine Horwill, Elli Thomas龐凌波 譯/Translated by PANG Lingbo

被排除在外是怎樣的感覺?

想象一下你在使用輪椅時的情景。你試圖搭乘列車去工作,卻因為車站的電梯許久未維護,無法到達站臺。你試圖尋求幫助,卻并未找到工作人員,于是不得不叫來出租車。搭乘出租車的開銷是地鐵的5 倍,而且這樣一來你上班就遲到了。在英國,每10 人中就有一人有行動障礙,這種情形對于他們而言幾乎等于日常。

再想象一下你有焦慮性障礙的情景。你依然試圖搭乘列車去工作,然而站臺上水泄不通,車廂內擁擠不堪。這簡直令人崩潰,于是你轉身離去,返回家中。你在那一天沒有去上班。在英國,每25人中就有一人有心理障礙,對他們而言,這就是每天必須面對的情形。

那么,再想象一下你是一位女士。這一次是在下班路上,車站站臺和回家路上沒有路燈,一片昏暗,目之所及沒有行人,也沒有房子或商店能夠眺望到這條街。你會感到擔憂和恐懼,于是你換了另一條路,一路屏息,直到走進家門才松一口氣。在英國,每兩人中就有一人在經歷這樣的日常。

這些事都說明了什么呢?第一個輪椅使用者的例子僅僅展現了有行動障礙的人們每天在建成環境中必須面對的其中一種困境,但在建筑環境中注意到“殘障人士”的困難是很容易的——這里的“殘障人士”通常指的是那些帶有永久性身體殘疾的人。第二個例子表明的則是非顯性的殘疾同樣會在其他方面——特別是一些普通使用者或設計者通常考慮不到的方面——對我們使用建筑空間的能力造成影響。第三種情況,著眼于體現人們是如何在一些并不歡迎他們、并不安全或并不為他們所設計的空間中被排除在外的,其中能夠導致這一情況出現的因素,包括性別、年齡、性取向及其他等等。每個人的體驗都是不同的,不僅因為我們都會衰老或受傷而不同,還因為我們的性取向、性別、種族,以及是否有小孩等而有所不同。我們需要拓展自己對于這種差異性在于什么的理解,并考慮如何通過這種理解來減少體驗上的差異感。

包容性設計不僅僅提供基本的物理可達性,而是為每個人創建更好的解決方案,確保每個人能夠平等地、自信地、獨立地使用建筑、交通工具和公共空間。包容的環境,是一種能夠被每個人安全地、便捷地、有自尊地使用的環境。它是方便舒適的,沒有阻礙的,讓無論哪類群體都能夠在無需付出更多努力、無需分隔或特殊對待的情況下獨立使用。

對于建筑行業而言,實現這一目標絕非易事。它需要決定性的系統層面和文化層面的轉變。這種類型的變革最好通過自上而下的領導和自下而上的公約和改變來實現,兩方共同建立必要的框架和正式的機制,以引導行業的發展、促進從業者的理解、培養從業者的技能,同時嘉獎優秀的實踐。

包容性設計最廣泛的意義已經超越了單一建筑或空間的概念。它是一種設計方法,可以解決主要的如生存劣勢、健康、幸福和經濟彈性等問題。建筑環境是人們工作、社交和獲得服務的基礎,若不對它善加考慮,將很有可能因為一些不必要的如不良交通接駁、住房短缺及基礎設施脫節等問題,降低人們獲得工作、社交及健康服務的機會,從而加劇不平等。如果包容性設計考慮得當,我們的建成物理環境可以通過降低不平等、讓更廣泛的群體能夠參與進來,進而促進社會的發展。

創建讓更多人可以積極參與生產的環境具有良好的經濟意義。在英國,共有1330 萬殘障人口,他們及他們的朋友、家人和同事的總消費能力為2490 億英鎊。確保這些殘障人士能夠使用和獲得服務,對于企業和組織來說具有良好的經濟效益。

而且,并不僅是因為這樣做是正確的,或是這樣做能產生經濟效益,包容性設計與我們的身心健康同樣息息相關。在英國,每6 人中就有一人是因缺乏運動而死亡的,40%的英年早逝的主要原因在于行為模式。越來越多的證據表明,建筑、街道、公園和社區的設計方式能夠對維持人們良好的身心健康起到作用——通過將健康的活動和體驗融入人們每日的生活,能夠減少健康的不平等,提升人們的幸福感。

倫敦哈克尼區的當地政府正致力于在整個區倡導更健康的環境。最近,倫納德馬戲團已從一個標準的柏油路交叉口改造成為一片鋪砌路面的以騎行者和行人為主體的共享街道空間。這是通過拆去路邊石、道路標記和交通標志實現的。標準的瀝青被磚和花崗巖取代,到處都是樹蔭和座位,提倡機動車慢行,以便人們能夠行走和坐下休憩。這個空間還能夠容納小型市場和其他活動,促進進一步的社交互動。雖然這樣的共享空間并不適用于所有人,倫納德馬戲團向我們展示了如何利用設計來激勵更健康的行為。此外,該區還采取了一定的措施,改善自行車道,確保在特殊車道上騎行者們的道路安全。其中包括交通管理措施,如指定車道、封閉道路及共用交叉口。這兩個項目的結果是,行人和騎行者都感覺更安全了,也由此鼓勵他們采用更健康的替代方式交通。

2哈克尼區倫納德馬戲團和健康空間營造/Leonard Circus and Healthy Placemaking in Hackney. (攝影/Photo: Catherine Horwill)

1 作為要求的包容性設計

英國有一套全備的法律和規劃體系,通過各種方式倡導無障礙和包容性場所并提出具體要求。這個體系具有多個層次,從議會法案到國家規劃架構、地方規劃,再到詳細的建設法規、規范和標準。

“2010 平等法案”是議會的一項法案,它是最高級別的對個人權益、機會平等的保護和促進。“平等法案”承認9 項受保護的特征,包括年齡、殘疾、變性、婚姻和民事伴侶關系、懷孕和生育、種族、宗教和/或信仰、性和性取向。“平等法案”還提出了與殘障相關的對現有建筑進行“合理調整”的要求。當該法案于2010 年首度出臺時,為了確保合規,“合理調整”的要求引發了英國各地對公共空間和建筑的改造。盡管坡道和電梯在提高物理層面的無障礙性方面不可或缺,但這種方式很可能會與現有的建成環境之間產生矛盾,而且很可能事后就會后悔(圖3)。一些在實現法規要求方面的優秀案例則表明,無障礙的需求需要在設計的早期階段進行考慮,以避免難看的、昂貴的翻新。

新倫敦規劃草案的最開頭第一項政策名為“建設強大包容的社區”。文件概述了指導大倫敦地區發展和土地使用的戰略政策。它的意義遠遠超越了無障礙的概念,已延伸到阻止人們獲得相同機會的不平等問題,倡導所有倫敦人都能平等地享用社交和經濟基礎設施。這一里程碑式的政策建立了一個框架,成為了規劃決策的決定性考慮因素,確保倡導包容性設計的提案能夠得到廣泛認可。

中央政府之外,許多組織機構也正在投資于包容性設計,一部分是出于法規的要求,但更多的是出于商業意義。近期,英國主要鐵路網的所有者和管理者英國鐵路網發布了《我們的良好設計原則》(圖4),作為一份戰略文件,它將影響未來英國鐵路網所有的發展。文件概括了該組織的主要戰略要點,其中一點就是他們所有的建筑和公共空間具有“包容性”。這項策略不僅認識到確保他們的設施對所有人可達的重要性,而且還認識到交通基礎設施在解決諸如經濟彈性、社會不平等和健康等重大社會問題上所具有的潛能。

3 一處包容性入口:薩德勒·威爾斯劇場,倫敦/An Inclusive Entrance: Sadlers Wells Theatre, London (攝影/Photo: Theo Harrison)

這一包括立法、政策、規范在內的多層次的體系,為包容性設計創建了一個框架,因其高瞻遠矚,對包容性設計在英國的蓬勃發展起到了至關重要的作用。不過,自上而下的實現包容性設計僅能夠確保行業內在文化層面上的改變。而為了讓從業者們在實踐中不只停留在屈從和滿足最低標準的層面,包容性設計的理念需要真正被建筑行業的從業者們接納。

2 包容性設計實踐

那么從業者們要如何在實踐中運用包容性設計?對于那些在英國建筑行業中工作的人來說,挑戰之一是從業者之間的競爭和偶爾沖突的需求。在理想的情況下,社會效益和使用者的需求是所有建設項目的主要目標。而在現實中,我們需要平衡這些目標與金錢、時間及過去的經驗的關系,有時這就帶來了挑戰。

我們的愿景是使包容性設計成為設計過程中的第二天性。為了賦予從業者們以信心、知識和許可來實現包容性設計,我們設計委員會開發了一種關于包容性環境的免費1 小時在線培訓課程,旨在為60 萬英國建筑專業者提供技能、建立信心、賦予權限,將包容性設計理念融入他們的工作。培訓課程提出了5 項成功創造包容性環境的原則。我們建議所有的從業者在設計的全過程中都采用這5 項原則,不僅牢記這些原則,并以這些原則來檢驗設計方案。這些原則結合了上述關于包容性設計為何具有社會和經濟意義的論據,提供給從業者和決策者雙方,旨在使包容性設計在兼顧其他要求和考慮的情況下更容易實現。

5 項包容性設計原則:

(1)以人為本:包容性設計將人放在設計的核心位置;

(2) 多元差異:包容性設計承認多樣性和差異性;

(3)提供選擇:包容性設計提供單一設計策略無法提供的多樣選擇;

(4) 使用靈活:包容性設計具有使用上的靈活性;

(5)積極體驗:包容性設計使建筑環境對每個人都便捷舒適。

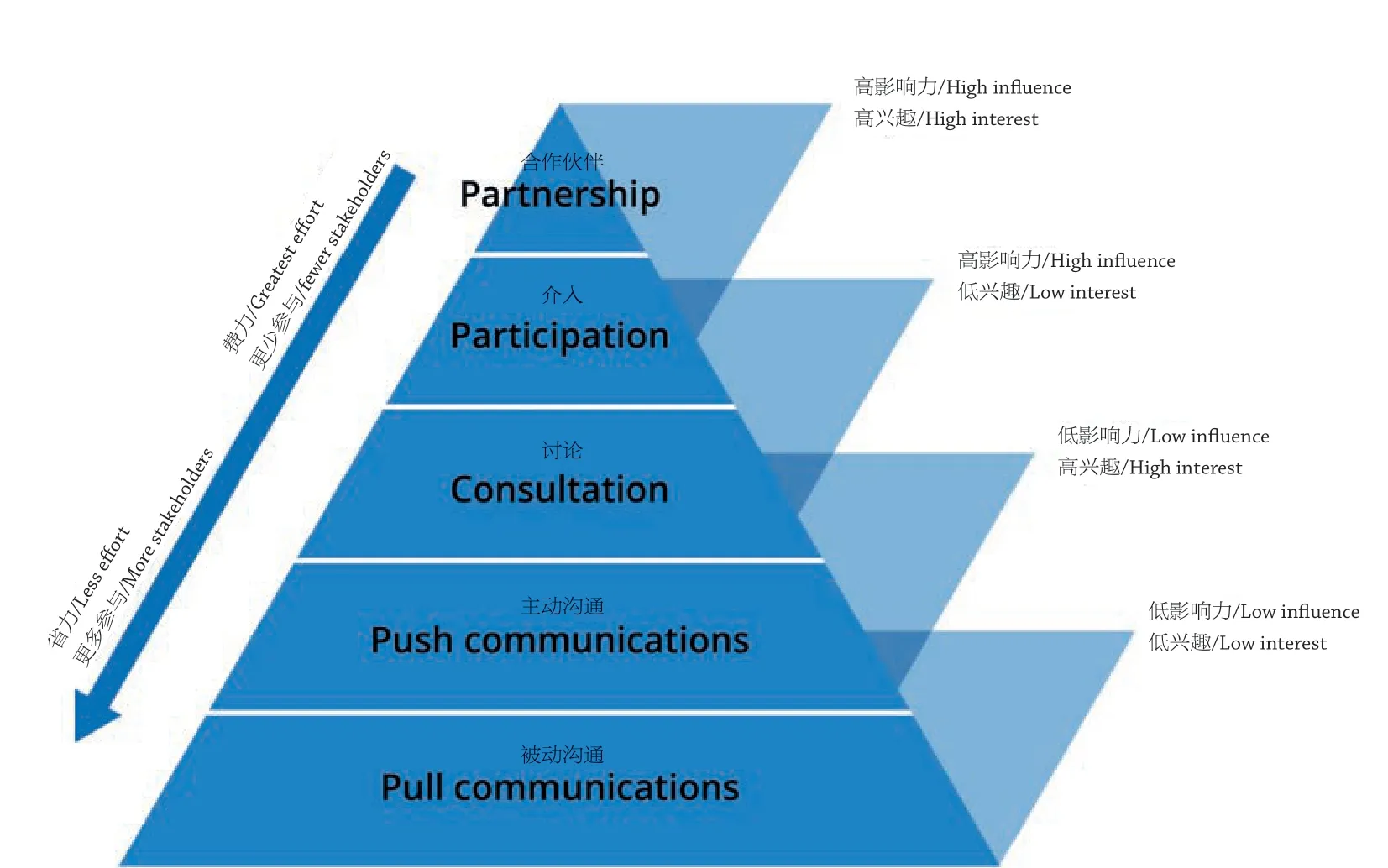

使用者積極的參與是包容性設計的基礎,這并不令人意外。只有理解那些將使用或會受開發項目影響的人的需求,我們才能進行設計,并最終得到滿足他們需要的一棟建筑、一個空間或一座城市。這個過程由利益相關者的映射開始,即辨認哪些人群牽涉其中,然后形成有效且合宜的參與策略,讓他們的意愿能夠介入設計過程。能有效地實現這一點,通常意味著已經跨越了基準需求。在英國,在規劃過程中對公眾參與的法規要求極為有限。當一項規劃申請被提交之時(也即設計工作正式開啟之時),關于提案的信息將會發布在當地政府的網站上,信件也會寄送至當地的居民手中,接下來就是為期21 天的討論,開放給公眾和其他利益相關團體考慮提案和反饋意見。這往往太短、也太遲了,而且往往會引發懷疑和怨恨。但我們可以也常常做得比這要好。下面的圖表“參與之梯”(圖5)列出了不同層次的參與形式。剛剛描述的法定的討論,屬于“被動溝通”一層,即一個人可以獲取信息但沒有信息輸入。參與的程度會隨階梯一路上升至“合作伙伴”一層,在這個層級人們成為了共同決策者。參與的適宜程度與努力的適宜程度取決于項目本身。但選擇合適的程度,并且讓用戶參與成為設計過程的核心,對于獲得認同、充分理解并為這些利益相關者設計而言,至關重要。

4 《我們的良好設計原則》/Our Principles of Good Design ?Network Rail

用戶參與的最佳介入方式是特別注意那些在過程中很可能被忽視的人,或是那些觀點很可能不會被采納的人。這并不僅僅指那些身體殘疾者,還涉及學習困難、精神疾病、視聽障礙者,而且還要將對不同年齡、種族、性別的人們體驗空間的不同的理解納入考慮。

伯明翰圖書館,由伯明翰市議會委托麥肯諾事務所設計并于2013 年完工,在其設計過程中,包容性設計和用戶參與從一開始就得到了恰當的考慮。在設計的早期階段,該項目就發現現有的圖書館使用者中有30%來自非白人少數族裔,13%有身體殘疾,20%是退休人士,10%是失業者,而且成年使用者的33%年齡在24 歲以下。用戶參與設計的計劃特別明確地針對了這些群體,確保這些利益相關者都能夠參與到設計過程中來。

伯明翰圖書館的例子也表明了,在設計最開始對利益相關者的甄別,以及他們在過程中的參與,是怎樣有助于設計者與未來用戶建立共同愿景和認同感的。包容性設計方法對任一階段都十分重要,因此,我們也不只會在設計階段考慮使用者的需求。除了在構思階段和撰寫報告時,我們還可以在施工和使用階段繼續考慮使用者需求。位于利物浦的19世紀平民劇場,在2011-2014 年間進行了重建,由霍沃思-湯普金斯建筑事務所設計,恩斯克里夫-戴維斯合伙人事務所提供無障礙咨詢服務。設計基于與當地社區、劇院熟客、作家、演員、文保組織及其他文化機構的討論,并建立了一個公開的論壇,來宣講整個設計過程。這個論壇還在施工階段組織了一系列的現場參觀,來告知人們一些諸如引入電動插座為輪椅充電、使門的顏色對比鮮明便于識別方向等重要的細節。

對包容性設計的運用也可以體現在當一棟建筑或一個空間處于使用中時對其的考慮——這一點常常在設計過程中被遺忘,這包括了對空間的物理維護,例如電梯的維護,而且還包括了我們如何為人們的情感和智力需求提供保障。這可能意味著一些懂得如何幫助有不同需求的人的訓練有素的工作人員,也可能意味著要為人們提供足夠的信息——往往在他們離開家之前,通過例如網站或應用程序實現這一點,來使他們有足夠的信心造訪某棟建筑或某個空間,并且在到達時感覺受到歡迎。

5 參與之梯/The Ladder of Participation

除了這些之外,還有另一種方法對于鼓勵從業者們變得更加包容非常重要:那就是變得現實。沒有哪個建筑或空間能夠100%無障礙或包容,就像沒有哪個地方能在其他方面完美無缺一樣。包容性設計是為盡可能多的人創造盡可能好的環境。對于大多數的項目,總有許多利益相關者在一些方面會持不同意見,或兩種要求相互矛盾。設計者與利益相關者之間的關系在這里非常關鍵,而且通常圍繞二者的關系,會產生創造性的解決方案,讓建立共識成為可能。在實踐中,通過讓利益相關者一起參與到決策的過程中,考慮限制因素,并討論如何克服它們,有助于形成用戶能夠理解并承認的決策,而不是讓人們感到被決策的過程排斥在外。在難以達成共識的地方, 一些規范和標準能夠有助于達成有原則性的公平的結論。我們設計委員會在實踐中會采用的一項標準是“不便與排外”的:也就是說,采取某項決策為某個使用者帶來不便(例如在公交車上推著嬰兒車的人,可能需要將它折疊收藏起來),是為了避免另一個使用者被排除在外(例如若非如此,坐輪椅的人就無法乘坐公交車)。

3 實踐成果及其后續

當然,對我們設計委員會而言,可以很清楚的看到,在一些現有的和新落成的項目中,英國的從業者們在其工作核心采用了包容性設計的理念——從奧利匹克公園,這個創造了“有史以來無障礙最優的奧運會”,以及一座為公共空間無障礙制定了最新標準的公園,到在英國各地建立的數個瑪吉中心,這個由非預約式癌癥治療慈善機構形成的網絡,每處機構都經過單獨設計,旨在創造鼓舞人們精神的空間,為他們的健康治療發揮重要作用。不過這些案例還不算常態。英國住房協會Habinteg 最近的一項調查顯示,在英格蘭各地議會制定的地方規劃中,只有不到半數對一定比例的新建房屋需滿足任何形式的無障礙住房標準提出了具體要求[1]。而在發布住房數據以響應住房環境的壓力較大的地區,開發商仍然需要優先考慮利潤,將注意力轉向質量和用戶是一種持續的壓力。那么我們怎樣才能帶來這種文化層面的變革呢?

正如前面所討論的,我們可以設定規范,將立法、政策和引導結合起來,這也是英國所擅長的,使包容性設計成為一種要求,而不僅僅是一種愿望。在這方面,我們還有很長的路要走,中央和地方政府,以及那些參與規范基礎設施、建筑環境質量的人們,仍可以繼續發展下去,制定出清晰的、可執行的、有雄心的監管規定。

當然我們希望看到的不僅僅是這些。我們希望包容性設計可以成為決策者、開發者和從業者的第二天性。這意味著要改變所有參與創造建筑環境的人的觀念,這樣他們才能認識到包容性設計是我們的首要任務,是實現社會與經濟價值的基礎,而不僅僅是一個附加功能。

這意味著要塑造每個參與創造建筑環境的人的理解、技能與能力——從在威斯敏斯特擬寫新政策的政客,到撰寫報告的開發商,再到第一次與客戶會面時的建筑師,以及那些維護和管理空間設施的人員。

這還意味著一步步的文化變革的實現,通過展示我們成功的案例,通過在每個階段支持包容性設計,通過開啟和持續這種對話——這將成為一種新常態。□

What does it mean to feel excluded?

Imagine for a moment you use a wheelchair. You try to take the train to work - but the lift at the train station hasn't been maintained and you can't access the platform. You ask for help but there aren't any staff available at the station, so you call a taxi instead. It costs you 5 times the price of the train fare, and you're late for work. For one in 10 people in the UK, who have a mobility impairment, that could be an everyday experience.

Then imagine you have an anxiety disorder. Again, you try to take the train to work - but the platforms are overloaded and there's a crush on the train. It's too overwhelming to deal with, so you turn around and go home. You don't go to work that day. For one in 25 people in the UK, who have a mental health impairment, that's another everyday experience.

And now imagine you are a woman. This time, on the way home from work, the platform at the station and the street to your house aren't lit, there are no people around, and there are no houses or shops that overlook the street. You feel threatened and scared - so you divert your route, hold your breath, and only release it once you get inside your house and close the door. For one in 2 people in the UK, that's another everyday experience.

What do these anecdotes show us? The first example of the wheelchair user shows just one of the any barriers that those with physical disabilities face in using the built environment. But it's easy to be focussed on 'disability' in the built environment and by that we usually mean those with permanent physical disabilities. The second example shows how a non-visible disability can affect our ability to use the built environment in other ways, particularly in ways that we don't always think about either as users or as designers. And the third starts to show how people can be excluded from spaces that are not welcoming, safe or designed for them - and that can be because of our gender, age, sexuality or other characteristics. And we all experience difference - not only do we all get old, or injure ourselves, we also all experience the city differently because of our sexuality, gender, race, whether we have children, and so on. We need to widen our understanding of what this difference is and how we can take it into account to reduce the experience of difference.

Inclusive design goes beyond providing physical access and creates solutions that work better for everyone; ensuring that everyone can equally, confidently and independently use buildings, transport and public spaces. An inclusive environment is one which can be used safely, easily and with dignity by all. It is convenient and welcoming with no disabling barriers, and provides independent access without additional undue effort, separation or special treatment for any group of people.

For the building industry, achieving this is no small feat. It requires a significant systematic and cultural shift. This type of change is best achieved through leadership from the top and commitment and change from the bottom, which collectively help to put in place the framework and formal mechanisms necessary to guide industry as well as develop practitioners' understanding and skillset, whilst also highlighting best practice.

Inclusive design in its broadest sense goes beyond a single building or space. It is a design approach that can address major societal issues such as disadvantage, health and well-being and economic resilience. The built environment is the framework in which people work, socialise and access services. If it is not properly considered, it has the potential to exacerbate inequality by reducing people's access to jobs, social networks and health services through unnecessary barriers such as poor transport connectivity, housing shortages and disconnected social infrastructure. When inclusive design is considered well, our built environment can uplift a society by reducing inequalities and enabling a wider group of people to participate.

Creating an environment which allows more people to participate actively in the economy makes good economic sense. And in the UK, where there are 13.3 million disabled people, the combined spending power of disabled people and their network of friends, family and colleagues is £249 billion. It makes good financial sense to businesses and organisations to ensure that disabled people can use and access their services.

And it's not just about being the right thing to do, or about the economic sense - it's about our health, too. Physical inactivity is responsible for one in six UK deaths and behaviour patterns are responsible for 40% of the cause of premature death in the UK. A growing body of evidence is demonstrating how the design of buildings, streets, parks and neighbourhoods can support good physical and mental health, help reduce health inequalities and improve people's wellbeing by building healthy activities and experiences into people's everyday lives.

In London, the local authority in Hackney is working hard to promote healthier places across the borough. Recently, Leonard Circus was transformed from a standard asphalt road intersection to a paved, shared street space that promotes cyclists and pedestrians over vehicles. This has been achieved through the removal of kerbs, road markings and traffic signs. Standard asphalt has been replaced by brick and granite with trees and seating throughout, encouraging vehicles to drive slowly and enabling people to walk and sit. The spaces can also accommodate small markets and other events, promoting further social interaction. While shared spaces don't suit everyone, Leonard Circus shows how design can be used to support healthier behaviour. Additionally, measures have been taken across the borough to bolster cycle routes and ensure that prominent routes are safe for cyclists. This has included traffic management measures such as designated lanes, road closures and shared crossings. The result for both projects is that pedestrians and cyclists felt safer and more encouraged to use healthier, alternative modes of transport.

1 Inclusive design as a requirement

The UK has a comprehensive legal and planning framework that in various ways both makes requirements for and advocates for accessible and inclusive places. This system is multi-layered, ranging from Acts of Parliament, to national planning frameworks and local plans, to detailed building regulations, codes and standards.

The Equality Act 2010 is an Act of Parliament that at the highest level protects the rights of individuals and advances equality of opportunity for all. It recognises 9 protected characteristics, which are age, disability, gender reassignment, marriage and civil partnership, pregnancy and maternity, race, religion and/or belief, sex and sexual orientation. The Equality Act also contains a requirement for "reasonable adjustments" to be made to existing buildings in relation to disability. When the Act was first brought in during 2010, the requirement to make "reasonable adjustments" triggered retrofitting of public spaces and buildings across the UK to ensure compliance. While ramps and lifts are crucial in facilitating physical access, this approach can be at odds with the existing built environment and very much an afterthought (photo). Good practice in fulfilling the requirements suggests that access requirements are thought about at early design stages, to avoid unsightly, expensive retrofitting.

The very first policy in the new Draft London Plan, the document which outlines strategic policies to guide development and the use of land in Greater London, is entitled "Building strong and inclusive communities". It goes far beyond accessibility, referencing the inequality that inhibits some people from accessing the same opportunities as others; advocating for equal access to social and economic infrastructures for all Londoners. This landmark policy puts in place a framework that will act as material consideration in planning decisions, ensuring that proposals that promote inclusive design are looked upon favourably.

Outside of central government, organisations are investing in inclusive design, partly because of the required legislation but also because the business case makes sense. Recently, Network Rail, the owner and manager of the majority railway network in Britain, produced "Our Principles of Good Design", a strategic document that will impact all future Network Rail development. The document outlines the organisation's key strategic priorities, one of which is to make all their buildings and public spaces are "inclusive". The policy recognises the importance of ensuring their property is accessible to all but also recognising the potential for transport infrastructure to address significant societal issues such as economic resilience, social inequality and health.

This multi-layered system of legislation, policy and standards is essential in creating a framework for inclusive design to thrive within the UK, as it sets expectations from the highest level. However, a topdown approach to inclusive design can only go so far in ensuring a true culture change across the industry. In order for practitioners to ensure their projects go beyond compliance and meeting the minimum standards, inclusive design needs to be embraced by those working across the built environment industry.

2 Inclusive Design in Practice

So how can practitioners adopt inclusive design in practice? One of the challenges for those working in the built environment in the UK are the competing and occasionally conflicting demands on practitioners' within the design process. In a perfect world, social outcomes and the needs of the user would be the primary objective of any built environment project. In reality, we need to balance this with money, time, and the historic ways of working that sometimes make this challenging.

Our vision is to help make inclusive design second nature within this process. To help give practitioners the confidence, knowledge and permission to deliver inclusive design, we at Design Council have developed a free hour-long online training course on inclusive environments that aims to give the 600,000 built environment professionals in the UK the skills, confidence and permission to embed it into their work. The training sets out five principles to creating successful inclusive environments, which we advise all practitioners to use throughout the process to keep in mind and test proposals against. In combination with equipping both practitioners and decision-makers with the arguments set out above for why inclusive design makes social and economic sense, the principles aim to make inclusive design more achievable in the context of all the other requirements and considerations.

The five principles of inclusive design

(1) People First - Inclusive design places people at the heart of the design process.

(2) Diversity and Difference - Inclusive design acknowledges diversity and difference.

(3) Choice - Inclusive design offers choice where a single design solution cannot.

(4) Flexibility - Inclusive design provides for flexibility in use.

(5) Positive Experience - Inclusive design provides buildings and environments that are convenient and enjoyable to use for everyone.

It shouldn't come as a surprise that good engagement with users is fundamental to inclusive design. It is by understanding the needs of those who will use or be affected by a development project that we can carry out a design process and end up with a building, space or city that meets their needs. This process begins with stakeholder mapping, to identify who these people are who need to be engaged, and then developing an effective and proportionate engagement strategy to bring these voices into the design process. Doing this effectively often means going beyond the baseline requirement. The statutory requirements for public engagement in the UK as set by the planning process are extremely limited. Once a planning application is submitted (which is once the design work has already been carried out), information about the proposals is published on the local authority's website, letters are sent to local residents, and the consultation is open for 21 days for the public and other stakeholder groups to consider and respond. All too often, this is too little and too late, and can prompt mistrust and resentment. But we can and often do a lot better. The diagram below (fig.5) illustrates the "ladder of participation", which sets out the different levels at which we engage. The statutory level of consultation just described sits is at the level of "pull communication" - where a person can access information but has no input. But the level of involvement increases all the way up to partnership, where people are joint decision-makers in the process. The right level to engage with people, and the right level of effort, depends on the project. But getting this right and making this process central to the design process is crucial in achieving buy-in, and fully understanding and designing for those people.

The best approaches to engagement take particular notice of those likely to be overlooked in the engagement process, or whose views are less likely to be accommodated. This doesn't just mean physical disability but impairments such as learning di☆culties, mental ill health, and vision and hearing impairments, and also taking into account an understanding of how people of different ages, races, ethnicities and sexualities experience spaces differently.

As part of the design process for Birmingham Library, which was commissioned by Birmingham City Council and designed by Mecanoo, and completed in 2013, inclusive design and engagement was considered right from the beginning. At an early stage, the project identified that of existing library users, 30% were from non-white ethnic minorities, 13% had a declared disability, 20% were retired, 10% were unemployed, and 33% of adult users were under 24 years old. The engagement plan specifically targeted each of these groups to ensure that these stakeholders were involved in the process.

The example of Birmingham Library also illustrates how identifying stakeholders at the outset and involving them in the process can help in established a shared vision and a sense of buy-in with the future users. Inclusive approaches are crucial at each stage of the process, therefore, and not just at the design stage, where we might typically think about user needs. As well as considering it at the vision stage and in writing the brief, we can also think about it at construction and in-use stages. The 19th century Everyman Theatre in Liverpool was rebuilt from 2011-2014 with designs by Haworth Tompkins Architects with access consultancy by Earnscliffe Davies Associates. The design process was based on consultation with the local community, theatregoers, writers, actors, heritage groups and other cultural institutions. An Access Forum was created to inform the design process throughout, and this Forum went on a series of walk-throughs at construction stage to inform some of the important details including introducing electric sockets to re-charge wheelchairs and contrasting door colours to help wayfinding.

The application of inclusive design can also be considered all the way through to when a building or space is in-use - something which is all too often forgotten in the design process. This includes both the physical maintenance of a space, such as maintenance of lifts, but also in how we make provision for people's emotional and intellectual needs. This can mean having trained staff who understand how to support people with different needs, and providing people with sufficient information, often before they leave their home such as through a website or app, so they are confident enough to access a building or space and feel welcome when they arrive.

And with all this in mind, there's another approach which is really important in encouraging practitioners to be more inclusive: which is that of being realistic. No building or space is 100 percent accessible or inclusive, just as no place is perfect in any other way. Inclusive design is about creating the best place possible for as many people as possible. And with most projects, there will be areas where many stakeholders have differing opinions, or two requirements appear to be in conflict. The relationship between the designer and the stakeholders is crucial here, and usually there is a creative design solution around which it is possible to build a consensus. In practice, by allowing stakeholders to go through a decision-making process together, to consider the constraints, and to discuss how to overcome them, helps to achieve a decision which users understand and can own, rather than letting people feel excluded by the decision making-process. And where consensus is hard to find, there are criteria that can help to reach a principled and fair conclusion. One that we at Design Council use in practice is that of inconvenience and exclusion: that is, taking the decision to inconvenience one user (such as a person with a buggy on a bus, who may be able to fold it up and stow it away) in order to avoid excluding another user (such as a wheelchair user who may otherwise not be able to use the bus).

3 Outcomes and next steps

It is certainly clear to us at Design Council that there are some existing and emerging best practice examples of where practitioners in the UK are putting inclusive design at the forefront of their work - from the Olympic Park, which created "the most accessible Games ever" and a park which sets a new standard for accessibility in public space, to a number of Maggie's Centres across the UK, a network of drop-in Cancer support charities which are each individually designed to create spaces that uplift people and play a crucial role in their care. But these examples are not yet the norm. A recent survey by the UK Housing Association Habinteg showed that less than half of local plans set by councils across England set a specific requirement for a proportion of new homes to meet any form of accessible housing standards.[1]And in a context where pressure is intense to deliver housing numbers to respond to a housing context and where developers still need to place profit first, turning the dial on quality and towards the user is a constant pressure. So how do we bring about this culture change?

6 伯明翰圖書館/ Birmingham Library

We can regulate, and as discussed earlier, the UK doing well in bringing together legislation, policy and guidance to make inclusive design a requirement and not just an aspiration. There's always further to go in this, and both central and local government and those involved in regulating the quality of our infrastructure and built environment can continue to develop this and set out clear, actionable and aspirational regulation.

But we'd like to see more than this alone. We want to make inclusive design second nature to policymakers, developers and practitioners. That means shifting the perceptions of all those who have a role in creating the built environment so that they recognise inclusive design as the top of our priority list, and fundamental to achieving social and economic value - not just as an add-on.

It means building the understanding, skills and capacity of everyone involved in creating the built environment - from a policy officer in Westminster writing new policy, to a developer setting a brief, through to the architect at a first client meeting, through to how facilities staff maintain and manage spaces.

And it means step by step bringing about culture change that shows that this is the new normal - by showcasing what we're doing well, by championing it at every stage, and by starting and continuing the conversation. □