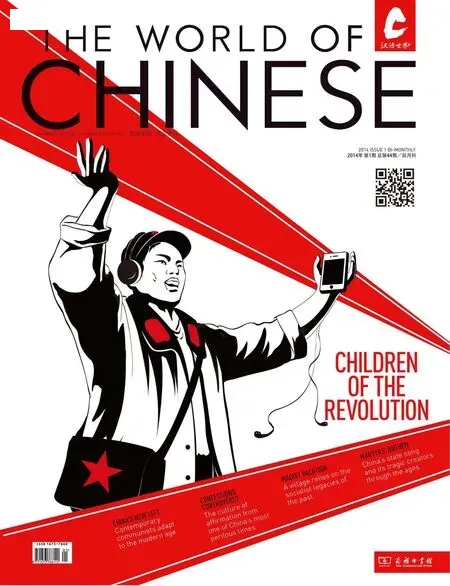

MARTYRS' ANTHEM

BY JAMES PALMER

MARTYRS' ANTHEM

BY JAMES PALMER

The tragic tale behind China's national call to arms

國歌背后的兩個悲劇天才

When it comes to national anthems, most countries are stuck with patriotic dirges or paeans to monarchy. Compared to these, China's“March of the Volunteers” (《義勇軍進行曲》) is a stirring piece, a cry to resistance, a

call for national pride, and a martial anthem. But the history of the song, and the tragic fates of its creators, speaks to the complicated and bloody appropriation of patriotism by the State.

“March of the Volunteers” started as a film number, composed in 1934 by young musician Nie Er (聶耳) and established playwright and lyricist Tian Han (田漢). There are plenty of romantic legends about the song's origins, such as the text being scrawled by Tian on tobacco paper after being thrown into a Shanghai prison by the Kuomintang. The real origins are more mundane; although Tian was temporarily in jail when the song was composed, Nie simply took the last stanza of a long poem, “The Great Wall”, Tian had written for an upcoming play and set it to his own rousing tune.

SHARED GENIUS

Nie and Tian shared similar backgrounds, although, at 35, the playwright was 13 years older than the baby-faced Nie. They both came from educated, upper-class families, Tian from Hunan and Nie from Yunnan. Inspired both by political fervor and nationalist sentiment, both joined the Communist Party in the early 1930s, throwing themselves into Shanghai's thriving left-wing drama scene. Both were English speakers looking to the West for how China's traditions and national spirit could be revived. And, like many Chinese intellectuals of the time, their intellectual life was tied to Japan, where they both frequently travelled. Tian studied drama there from 1916 to 1922, and Nie's brother was pursuing his education in Tokyo. Japan was a looming menace, but it was also an inspiration: an Asian nation that had gone from a backwater to a modern power in a few short decades.

At only 22, Nie was brilliantly talented, capable of picking up almost any instrument. His songs drew upon both classical and popular Western and Chinese forms, a swirl of melodies that produced consistent hit-making. Born Nie Shouxin, he gave himself the name Er, literally “ears,” after a classmate's nickname bestowed thanks to his musical skills. By 1935 he had written 41 pieces, mostly for theater or fi lm, their titles—“Village Girl beyond the Great Wall”, “Singing Girl Downtrodden”,“Song of the Broad Road”, “Song of the Newsboy”—hinting at their mixture of the sentimental and the political. The songs were themed around the patriotism of all Chinese, from educated overseas returnees to ordinary peasants to the euphemistic “singing girls”.

Tian was once as much of a prodigy as Nie, composing one-act traditional operas as a teenager. But it was his time in Japan that really made him, exposing him to modern Western dramatists who remade his ideas of what theater could be. He ditched class to go to plays and frustrate his fi ancée by hiswillingness to abandon dates with her for a chance to see a new production. Caught up in politics, he could annoy his literary contemporaries; Lu Xun (魯迅), China's greatest modern writer and a friend of Tian's, once dubbed him one of the “four villains” whom he disagreed with most.

Tian spoke of wanting to be the “Ibsen of China” and ditched the high-toned language of traditional theater for the vernacular, telling stories of ordinary Chinese and putting everyday modern life on the stage; his 1922 play is called, wonderfully,A Night In A Coffee Shop. But he looked to older Western sources as well, providing the fi rst translation ofHamletinto vernacular Chinese in 1921 andRomeo and Juliettwo years later. He saw literature as the heart of a nation, quoting with approval Thomas Carlyle's claim that the British could live without India, but not without Shakespeare. His patriotism was such that, born Tian Shouchang, he renamed himself Han, as in “Han Chinese”.

As well as dramatists, his heart was captured by Walt Whitman, whom he saw as the great “bold and pure soul” of the US, the epitome of, in his words, “the song of freedom they (Americans) have composed.” With a practical interest in directing as well as writing, he built stories around elaborate visual and audio effects; the roar of a tiger, the light of a distant mountain, the chatter of a village square. These skills made him a natural for the burgeoning Shanghai fi lm industry, and his passion for the cinema was such that he ruined his eyesight in dimly-lit theaters. Today, many of his plays can seem clumsy, especially after he moved away from the commitment to literature of his early years to a more didactic political approach by the early 1930s, but in the Chinese theater world, he was part of a revolution. His political sentiments led to a brief imprisonment by the Kuomintang; his popularity won him a release.

With this duo of genius behind it, it was no wonder the “March”was a success. It hit the public in two forms; in the fi lmSons and Daughters of the Storm(《風云兒女》), fi rst screened at Shanghai's Jincheng Theater on May 24, 1935, and in a popular recording by EMI Music released at the same time. The fi lm was sentimental agitprop with a communist bent, designed to stir up anger against the Japanese occupation of Manchuria and inspire national resistance and revival. The most striking scene is the last, where the “March” is sung as the fi lm cuts to the tramping, sandal-clad feet of the peasant and worker volunteers, along with the formerly decadent intellectual protagonist, hefting rif l es and preparing for the national struggle ahead.

The “March” long outlived the fi lm it was composed for. It became one of the most popular songs in China, especially after full-blown war with Japan began in 1937. It was reprinted in newspapers, sung in brothels and pool halls, hummed by guerrillas in the mountains as they prepared for battle. By 1939, African-American singer and Communist activist Paul Robeson was singing it in concert, in Chinese, in sympathy with the struggle against imperialism. While its origins were on the left, it was equally popular with Nationalists as Communists.

But Nie never knew his own success. By the time the film premiered, he was in Japan, visiting his brother in Tokyo. Just two months later, he drowned while swimming in the ocean. Rumors immediately circulated that the death was no accident and that Nie, who may have planned to travel to the Soviet Union after Japan, had been murdered either by Kuomintang agents offended by his Communism or Japanese secret police determined to rub out a source of Chinese nationalism. The truth remains unknown. Dead at 23, the young musician's remains were brought back to Yunnan three years later, buried at the foot of the Biji Hills where he spent his childhood.

Tian Han was temporarily in jail when he composed China's National Anthem

HECTIC LIFE

Tian's life would prove far longer, and stormier, than Nie's, thanks to politics, war, and women. His plays, like his life, are full of passionate, often intellectual or artistic young women who inspire the protagonists to greater things. Tian, like many a stormy genius, was inclined to fall in love fast, hard, and frequently, without much regard for the sentiments of his current partner. By 1935 he was already on his third wife—and in a relationship with the woman who would become the fourth. Widowed young, he married his fi rst wife's classmate on her deathbed suggestion, but while he shared a strong friendship with his second wife, there was little passion. He fell in love by correspondence with a Shanghai teacher and married her in 1930—but by 1934 had fallen head over heels for An E (安娥), another scriptwriter.

Over the next decade, he would split his time between his wife and his mistress, with a daughter by the first and a son by thesecond, until divorcing and remarrying in 1946. Despite his success, he was often stone-broke, his daughter later recalling shoddy apartments and bare tables. Already thin, he became bird-like after working behind enemy lines to raise patriotic theater groups, putting on agitprop works in tiny villages well into Japanese territory.

The creation of the PRC seemed to set Tian up for good, especially after the “March”, already the unoff i cial national anthem, was off i cially conf i rmed in 1949. One of the lines caused the original committee, set up to decide on the song, some concerns; after all, could China really be in its “time of greatest peril” now the invaders had been repelled and the Communist Party ready to lead the country to a new era of prosperity? But Zhou Enlai, backed by Mao Zedong himself, came down hard, pointing out that the country still faced the threat of imperialism on every side. The song would reinforce the idea that the New China was in constant danger and that continuing bloody sacrif i ce was needed to cement the country's defences.

Tian was eager to play up the political nature of even his early works, helping secure himself a relatively comfortable position as a writer and artistic bureaucrat. But now in his 50s, he found that “liberation” came with a striking lack of freedom. The repressive nature of culture under the new regime, where ideology and Mao's personality cult came far before art, began to increasingly disturb him. In 1956, after the “Anti-Rightist Campaign” devastated China's intellectuals, he survived thanks to his impeccably patriotic credentials, but many of his friends were exiled to the countryside, imprisoned, or murdered.

He started to write plays and operas about artists, such as the Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368) playwright Guan Hanqing (關漢卿), faced with repression, using history to code his stories in ways he thought might be acceptable to the authorities. At fi rst, his works were applauded for exposing China's “dark, feudal past.” But for the puritans of the Cultural Revolution, neither Tian nor his “March” would prove acceptable.

Nie Er—a young, brilliant musician—was instrumental in the creation of "March of the Volunteers"

POISONOUS WEED

The fi rst salvos of the Cultural Revolution were fi red over drama. In November 1965, Yao Wenyuan, a far-left pseudointellectual who would later be one of the “Gang of Four”(四人幫), targeted the play by Wu Han (吳晗), deputy mayor of Beijing and a prominent historian,Hai Rui Dismissed From Off i ce(《海瑞罷官》). Wu Han was rapidly removed from off i ce and imprisoned for his tale of a noble off i cial forced out of his position, a story that seemed too close to the fate of general Peng Dehuai who opposed Mao over the Great Leap Forward and fell as a result.

Three months later, Tian was on the chopping block. His playXie Yaohuan(《謝瑤環》) was singled out in a front-pagePeople's Dailyarticle, “Xie Yaohuanis a Poisonous Weed.” Entire pages and even special supplements of papers were given over to attacking the 68-year-old playwright. The old half-joking slight by Lu Xun, that he was one of the “four villains,” was picked up as a sign that he was a traitor. He was arrested, and turned over to the Red Guards for humiliation and torture sessions, often lasting days at a time. After nearly two years of suffering, he died in a prison hospital having been denied medical care. His mother, nearly 100, and his wife, ill with tuberculosis, were turned out of their apartment, persecuted, and forced to live off the charity of relatives.

The song of a “villain” could no longer be an acceptable national anthem, especially given its disturbing failure to mention the Great Helmsman. And so the “March”became verboten, replaced with the sycophantic “The East is Red” (《東方紅》); a paean of praise to Mao which was compulsory singing at virtually all public events.

But the song outlasted the politics. In 1978, with the Cultural Revolution two years over,The East is Redwas quietly retired and the March noisily brought back. At fi rst Tian's lyrics were still too risky to reinstitute, leading to an absurdly clumsy mixture of Nie's tune with newly composed words that began “March on! Heroes of every ethnic group!” and continued with the reassurance that“We will for many generations/Raise high Mao Zedong's banner/March on!” But by 1982, at around the same time that the portraits of Mao nationwide were taken down “for cleaning”, the original lyrics returned; by 2004 they were enshrined in the constitution.

Nie, martyred in Japan, now has a prominent tomb in Kunming. Tian, martyred by his countrymen, is remembered by a massive theater and many streets bearing his name in his hometown of Changsha. And a song once meant as a crowd-pleasing fi nale to a fi lm is still the anthem of China.