舊石器時代考古中出土的赭石及相關遺物的研究方法

許競文 浣發祥 楊石霞

摘要:赭石是考古發現中一類較為常見的礦物顏料。遺址中的礦物顏料研究對于解讀中更新世以來人類行為的演化與發展以及人群的遷徙和交流互動具有重要意義。目前,我國出土和被識別的赭石相關考古發現日益增多,但研究程度還有待深入,舊石器時代考古發現中相關材料的識別和解讀較為有限。如何綜合利用多學科測試分析方法建立起完善的研究方案,深度挖掘赭石顏料利用所指示的人類行為發展模式和民族學意義,還需要我們進行系統性地總結和思考。因此,本文通過梳理現有的考古學、地球物理、地球化學和民族學等各領域的國內外研究成果,歸納了舊石器時代考古遺址中出土的赭石及相關遺物的主要研究內容——成分定性、產地溯源和加工技術分析,以及各自適用的分析方法。綜合多項研究案例,我們認為在性質、產地和技術分析的基礎上,需要結合民族學方法、生態環境背景才能更有效地解讀和復原史前人類的行為模式及社會學、民族學意義。

關鍵詞:舊石器時代;赭石;理化分析;人類學

1 引言

隨著考古發掘技術和科技測試手段的不斷提高,國內外舊石器時代遺址中除石器和骨器以外的諸多文化遺物也逐漸被發現,并得到深入研究,如顏料、藥物、特殊飾品等。這些具有特殊內涵的文化遺存進一步揭示了史前人類對自然資源的認知程度與開發能力,以及意識形態發展水平,對于深入認識漫長且復雜的人類行為演化歷程具有重要意義[1]。作為最易獲取的天然礦物顏料之一,赭石是較早被識別和確認的與人類意識形態活動相關的物質文化遺存,為史前藝術提供了鮮明的紅色系顏料。

赭石是一種天然的地質礦物,富含鐵的氧化物或氫氧化物,如針鐵礦FeO(OH)、赤鐵礦Fe2O3 和磁鐵礦Fe3O4 等[2]。赭石中含鐵組分的類別、含量及其晶體形態的變化決定了其條痕的色相、飽和度和明度[3]。故而采集不同類型的赭石能夠生產出或暗或明的黃色至紅棕色粉末,以滿足史前人類對紅色系“顏料”的需求。

史前人類利用赭石的歷史可以追溯到距今30~50 萬年前[4,5],隨后在全球各地發現了古人類更加豐富和多樣化的赭石利用行為[6-9]。史前遺址中赭石的出土形式通常包括:1) 保留了加工痕跡的碎塊或粉末,如加工成蠟筆狀的赭石、殘留在石磨盤上的紅色痕跡等[10-13];2)象征行為的直接證據,如巖畫、個人裝飾品上的涂色、埋葬中的赭石粉末等[14-22];3) 功能性利用的間接證據,如附著在石器末端的赭石碎屑殘留、赭石碎屑與牛奶的混合物,以及殘留在鹿牙裝飾品上的赭石、木炭和動物油脂混合物[23-26]。保存良好的赭石染色遺物遺跡相對稀少,全球各地分布零星,難以追蹤赭石使用模式的歷時性。盡管如此,記錄赭石加工技術的演變對于全面了解舊石器時代的赭石開發策略和族群文化面貌是至關重要的。

在通過土壤微形態分析等輔助手段排除原生埋藏地層受沉積期后改變的前提下,本文將總結如何綜合利用不同的測試方案,準確評估遺址中是否存在赭石顏料的利用及其利用方式和程度,并說明在文化習俗、宗教信仰、審美與社會等級制度等人類學研究方面,赭石的考古學研究所扮演的重要角色。

2 赭石的考古學分析方法及案例

認識赭石的理化性質、分析赭石的開發策略,是目前舊石器時代遺址考古中赭石研究的主要研究方向。目前應用于考古出土中赭石及相關遺物的具體分析方法包含表觀顯微分析和理化性質分析這兩個層次。表觀顯微分析是指利用顯微鏡觀測赭石表面的微痕,如坑疤、線性痕等。理化性質分析則是指對赭石進行物相或化學成分組成的測試分析以達到鑒定赭石所包含的礦物成分的目的。顯微鏡觀測、光譜學分析和巖石磁學等測試手段在研究實踐中可以實現以上兩個層次的分析,并有效地獲取赭石的礦物成分、產源及人類對其加工利用程度等信息。獲取考古遺址出土赭石的具體信息,有助于我們最終認識其所反映的當時人群流動性、資源獲取能力和象征行為等。

2.1 礦物成分分析

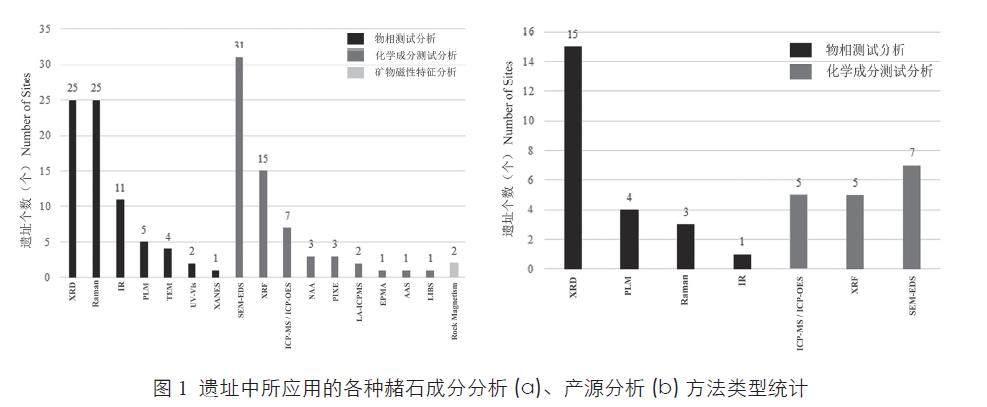

通過分析疑似樣品的物理化學性質,即礦物的元素百分比組合、晶體或分子結構和磁性特征,我們可以檢測出樣品的礦物成分[27,28],進而判斷樣品是否為赭石。筆者統計了已發表的54 例舊石器時代遺址中出土赭石及其相關遺物的研究方法[5,10-71],數據統計結果表明,分析礦物元素組合的常用測試手段包括X 射線熒光光譜分析(X-ray fluorescence,XRF) 和電感耦合等離子體質譜(Inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry, ICP-MS)等;用于分析礦物晶形或分子結構的常用測試手段則包括X 射線衍射(X-ray diffraction,XRD)、拉曼光譜分析(Raman)、紅外光譜分析(Infrared spectrometer, IR)、X 射線吸收近邊結構分析(X-ray absorption near edge structure, XANES) 和偏光顯微鏡觀察(Polarizedlight microscopy, PLM) 等(圖1: a)。另外,赭石的本質即含鐵礦物,其磁性特征由磁鐵礦、赤鐵礦、磁赤鐵礦的含量和粒度決定[72-74]。王法崗等人通過巖石磁學將下馬碑遺址中的樣品定性為赭石,這是中國近期在考古出土赭石的研究中應用巖石磁學的一項成功案例[13]。

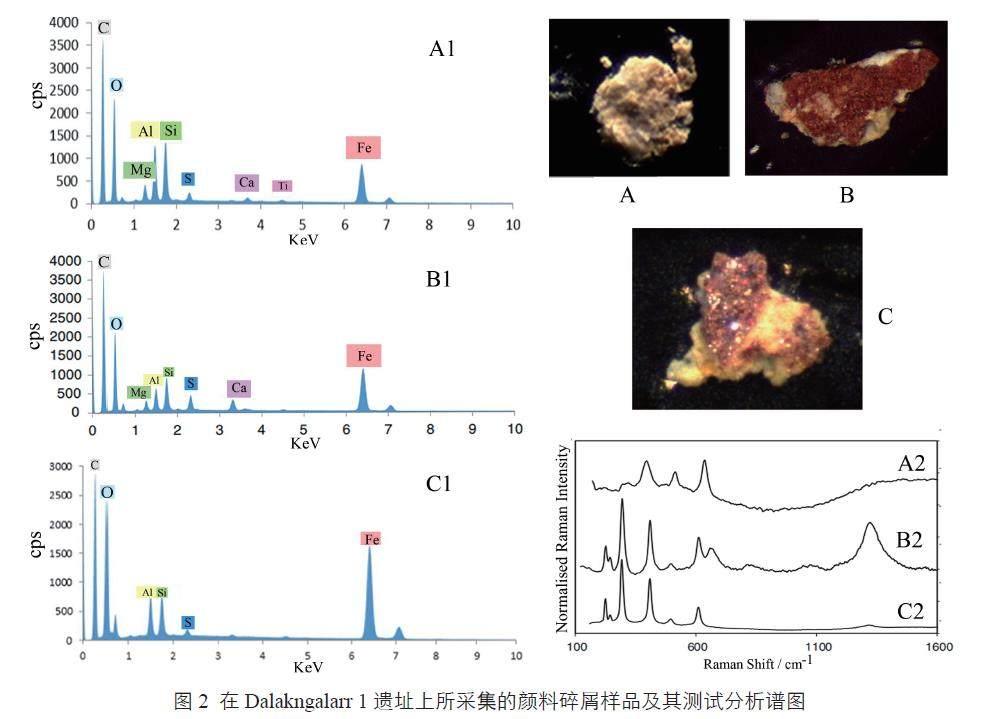

除了上述所提到的測試手段之外,掃描電鏡耦合能譜分析技術(SEM-EDS) 也是一種常用的理化分析手段(圖1: a)。掃描電鏡能譜分析技術具有很強的綜合性分析能力,可以耦合X 射線能譜儀、陰極熒光光譜分析等對赭石樣品的元素組成和晶體結構進行分析[75,76]。例如,澳大利亞北部的達拉肯加拉爾1 號(Dalakngalarr 1) 遺址[63] 發現了巖畫遺跡,在巖畫上采集少量的黃色、紅色和紫色碎屑樣品并用于掃描電鏡觀測,耦合能量色散X 射線光譜(EDS) 及拉曼光譜(Raman) 分析,確認了這三種顏色的微碎屑均為赭石(圖2)。

2.2 產地溯源分析

在確認研究樣品為赭石后,對礦物元素組合的量化和特征晶形的示蹤進行物源分析也是史前赭石的一個重點研究方向[77-80]。在溯源研究前,需要對遺址周邊進行地質調查,對所有大量產出含鐵礦物的地質區域進行定位,且采樣工作應盡可能地覆蓋整個露頭延伸的范圍[81,82]。本文統計了Fumane、Tagliente、Roc-de-Combe、Diepkloof、Tito Bustillo、MonteCastillo、Blombos、Hohle Fels、Vogelherd、Es-Skhul、Torajunga、El Mirón 等遺址[5,29,36-39,42,46,59,62]對赭石的產地溯源分析所采用的測試手段,其數據表明拉曼光譜、X 射線衍射分析、傅里葉紅外光譜和偏光顯微鏡等實驗能夠測試礦物的特征晶形以示蹤赭石樣品的產地,而X射線熒光光譜分析、電感耦合等離子體質譜和掃描電鏡能譜分析技術則是通過量化赭石中的礦物元素組合從而進行溯源分析(圖1: b)。其中,偏光顯微鏡(PLM) 的原理是利用晶體光學的性質對礦物進行巖相鑒定與分析[83]。該方法雖然能夠通過礦物的組構分析揭示其成礦原因,但是其溯源能力有限,目前僅有Cavallo 等人[62] 對Fumane 洞穴遺址和Tagliente 巖廈遺址利用此方法獲得了較好的溯源成效。值得補充的是,偏光顯微鏡觀測需要將巖石或礦物進行磨片處理,對考古樣品來說有巨大的損耗,因此研究者需謹慎選擇適用于該方法的赭石樣品,并在實驗前做好樣品的記錄工作。

Dayet 等人對位于南非開普的迪普克魯夫巖廈(Diepkloof Rock Shelter)遺址開展了系統的赭石溯源研究[37]。他們在遺址舊石器時代中期Howiesons Poort 工業的堆積中發現了數千塊赭石,通過X 射線衍射和微區拉曼測試并比對其黏土礦物的結構,準確識別出了較為可靠的遠距離源區。對比研究進一步顯示迪普克魯夫遺址的赭石開發模式與周邊其他同時期的遺址存在差異[41],具有一定的區域性特征,并可能與遠距離的人群互動和文化交流相關[69, 86-89]。總之,通過赭石的溯源分析來指示人群的活動范圍,能夠判斷是否存在遠距離運輸,并窺探史前人群的社會規模和結構[84,85]。

2.3 加工方式及其利用程度分析

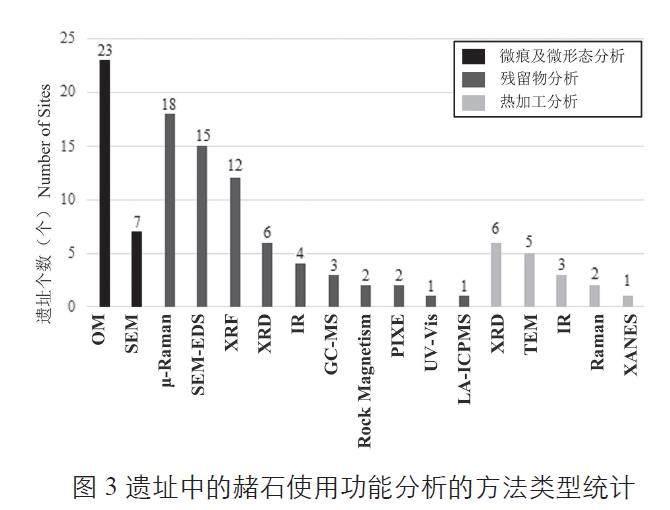

史前人類對自然資源的認知水平不斷提高,其表現形式包括開發出赭石的多樣用途、通過提取不同顏料的色素進行其意識的表達與刻畫等[7, 27,28, 68, 90-92],這些相關信息均可在對赭石的考古研究中獲得,因此舊石器時代考古出土赭石的另一個重點研究方向即復原人類對赭石的加工方式及利用程度。筆者通過統計Klasies River Cave、Hohle Fels、周口店、鴿子山第十地點、下馬碑、Altamira、Sibudu、Roc-de-Combe、Diepkloof、Porc-Epic、Blombos、Qafzeh、Bushman、Jerimalai、Fumane、Rose Cottage Cave、水洞溝第二地點等38個遺址應用于研究赭石使用與加工方式的測試手段[6,11-13,15,16,24-26,27-35,40,41,43,45,47-53,55-59, 63,66,68,70],將該研究方向的內容總結為微痕及微形態分析、殘留物分析和熱加工分析(圖3)。此外,根據赭石在遺址中不同的出土形式,可通過表觀顯微分析和理化性質分析來分步驟確定其功能。

顯微結構分析是在考古文物工藝研究中不可或缺的一種手段。顯微鏡觀測在赭石研究中的應用分為三種情況:一是直接對赭石碎塊進行表觀微痕分析;二是對人工制品表面微區的殘留物進行電鏡掃描,觀察其上是否具有赭石粉末的殘留;三是對赭石碎塊、人工制品或巖畫上的赭石染色殘留物進行透射電鏡掃描,通過其物相來判斷赭石是否由熱加工生成。在第一種情況中,表觀微痕分析(Usewear analysis) 是指利用顯微鏡觀測赭石表面的磨損痕跡,再通過比對實驗室的實驗結果,推測史前人類對其的加工使用方式[93,94]。赭石碎塊表面出現定向的平行擦痕意味著古人類曾通過在石磨盤等堅硬的器具上摩擦赭石以取得紅色粉末[95];較深的切槽說明古人類利用石器或骨器等工具對赭石進行刮削取粉[70];在其表面觀測到打擊點及坑疤,則可以推測古人類為便于摩擦取粉,在使用前將其敲擊成碎塊[29]。而掃描電子顯微鏡(SEM) 和透射電子顯微鏡(TEM) 的分辨率極高,具有較大的放大倍數,足以用于檢測人工制品上是否殘存赭色微碎屑[59,60,75,82]。掃描電鏡與透射電鏡的不同點在于:掃描電鏡只能得到樣品表面形態的信息;而透射電鏡依靠電子束成像,得到的是晶體中原子或原子團在特定方向上結構投影的信息,從而確定其晶體結構。透射電鏡的這一特點尤其適合運用于考古出土中赭石的受熱分析,即第三種情況。

對于埋葬中人工制品和巖畫上的赭石粉末遺存來說,利用掃描電鏡耦合能譜、拉曼光譜和氣相質譜等理化分析手段,可以對考古樣品進行殘留物的成分分析,進而對其來源和應用情況進行推理(圖3)[25,26,96]。周口店山頂洞史前穿孔飾品的再研究提供了一個可靠案例:通過掃描電鏡能譜分析技術檢測到三枚穿孔獾牙上的紅色殘留物均為赭石;同時,赭石染色的微區位置指示著穿孔獾牙可能曾被縫制于被赭石鞣制過的皮革衣物上[12](圖4)。更為有趣的是,獾牙飾品1、2 與獾牙飾品3 上殘余的赭石成分不同,加之穿孔加工技法不同,可能暗示了飾品是由不同個體或群體制作的。

此外,史前人類在舊石器時代晚期就已意識到加熱赭石能使其產生不同顏色[97]。赭石在受熱后,Fe-O 和O-O 鍵長會發生改變,其對稱性八面體結構扭曲,從而導致顏色加深[98]。因此,對赭石樣品的赤鐵礦分子結構進行測試后,便能夠得知其是否受過高溫作用。能夠進行該項測試的手段包括但不限于X 射線吸收近邊結構分析、紅外光譜分析、X射線衍射、熱釋光分析、透射電子顯微鏡、巖石磁學和拉曼光譜分析(圖3)。但是,我們仍需結合其他輔助方法以排除地質所導致的受熱因素,才能判定赤鐵礦分子結構的扭曲是否源于古人類的熱加工處理。在赭石研究中,對遺址進行土壤微形態分析,能夠更直觀地判斷考古埋藏中的赭石及石器上的紅色殘留是否源于自然埋藏過程的影響,如鐵質淋濾、原生磁性礦物的風化與搬運等。土壤微形態分析(Micromorphology Analysis) 對土壤進行顯微形態觀測和描述,通過顯微鏡鑒定土壤剖面的礦物組成、風化狀況等層相特征,排除遺址內地層后期擾動構造對遺存所造成的影響。該種方法一般需要在剖面上連續采樣,精準地評估微區環境演變對遺址形成的影響,分析考古遺存與古人類活動的關系[99,100]。

2.4 小結

綜上所述,對赭石開發策略的研究主要從產地溯源和加工方式及其利用程度這兩個角度出發,以地球物理化學測試手段和微觀顯微鑒定相結合的方法為主(圖5)。在眾多的地球物理化學測試手段中,XRF、ICP-MS 和Raman 等無損或微損分析測試手段得到了較為廣泛的使用。它們的優勢在于功能多樣化,不僅可以用于赭石的產地溯源,還能有效地揭示古人類對赭石資源的開發利用程度。而微觀顯微鑒定是考古學研究中的重要常規方法之一,該方法結合實驗能夠很好地推斷赭石表面微痕的產生原因。

近年來,愈來愈多的學者嘗試拓寬地球物理、地球化學與考古學的交叉研究和應用。例如,下馬碑遺址的研究將巖石磁學的測試手段引入赭石的考古學定性分析中[13],朱弗里洞穴(Jufri Cave) 遺址研究中應用XANES 分析法判斷赭石是否受到過熱加工作用等[30]。只有綜合利用不同的測試方法建立起適合的綜合研究方案,明確考古發現中赭石的原料經濟及其開發利用程度,才能最大程度地接近并復原史前人類的行為模式和社會文化。

3 赭石研究的人類學思考

史前人類對自然資源的認知發展最終催生出不同色彩的使用和裝飾品的制作等一系列超出基本生存需求的意識行為[101]。顏料與裝飾品等物質文化作為史前藝術的表現形式,隱含著人類對自我、他者關系的認知程度,承載著人類的精神文化和自我認知[102]。此外,作為身份和族群的標志,色彩和裝飾品既體現了不同族群的藝術創作和文化發展的水平,亦可能隱含各族群之間的關系 [103,104]。赭石是獲取“色彩”的重要物質資料,對赭石的研究是了解人類行為模式及族群文化的重要介質之一,其研究方法既借助了自然科學的理化分析,又緊密聯系社會科學中民族學、文化人類學等其他領域的解析理論。在前文中已經對各類自然科學分析方法及其應用情況進行了深入的解析,而此處我們將嘗試闡述如何建立起自然科學方法與社會學理論之間的關聯。

3.1 理化分析與行為重建

自然科學為考古發現中的無機顏料研究提供了豐富的定性及定量的理化分析手段[67,105],幫助研究者重建古人類的顏料使用行為模式。在此基礎上,學者可以廣泛地關注古代顏料,如赭石、朱砂、炭黑、青金石和孔雀石等,嘗試通過史前和古代藝術創作材料在時空上的變化去探究不同地理環境和歷史條件下各族群的意識形態[106]。例如,在西班牙阿達爾洞穴遺址(Cueva de Ardales),Afica Pitarch Martí 等人[11] 通過X 射線衍射測試發現洞壁上出現兩層不同源區的染色圖層,利用鈾系測年(U-Th) 得知其染色時間相隔兩萬年。這一行為被解釋成古人類對“祖先”地盤的標記,意味著早在4 萬年前古人類就已經在思考自我關系等哲學問題。

此外,地球物理化學常被用于古氣候環境的重建[107,108],可以有效地幫助恢復考古遺址區域內的古環境。棲息地的氣候環境、生態背景與人口規模和社會形態息息相關,是解釋人類行為模式的重要部分。環境背景直接影響區域內自然巖礦資源的可獲得性,以及人類獲取資源、交換資源的路徑[109]。在具體的研究中,地球物理、化學方法與考古研究相結合,有助于將生態適應、生產技術和人群擴散等因素串聯起來,為探討不同時空下人群和文化間的相互交流模式、活動空間變化提供更加全面且合理的解析[92,102,110],進而,這些綜合研究能夠更為恰當地解釋環境因素在人類行為演化進程中所扮演的角色。

3.2 民族學與社會文化的闡釋

舊石器時代遺址中赭石的利用是人類象征行為的考古學證據,亦被解釋為人類演化史中行為現代性的關鍵要素[91]。利用現代民族學材料的相關記錄是揭示赭石的史前用途及其加工過程的有效方法[111,112]。Rosso[70] 在研究埃塞俄比亞Proc-Epic 洞穴遺址中赭石粉末的粒度分析時,分別采集辛巴(Ova Himba) 部落和哈莫爾(Hamer) 部落用于涂抹頭發及身體和服飾的赭石粉末樣品,并開展了微痕實驗和量化分析,最終通過借鑒現代民族學研究直接重建了4 萬年前的赭石加工操作鏈。由于該遺址的地層序列跨時長達4500 年,出土赭石的標本量多至四千件,通過對不同類型的赭石及其處理方式的空間量化分析,有效地驗證了東非地區赭石的加工模式具有連續且漸進的變化。

不拘泥于某個遺址中赭石的具體用途,而是更多地關注赭石所指示的行為和文化內涵—— 在時空維度的變化和在人類生產生活各層面的應用,是進行赭石研究的最終目的。在考古學背景下,顏料和其他象征物都承載著人類的風俗習尚、生業方式與社會結構等文化演變與發展規律的重要信息[104]。解讀象征行為在人類族群分化與互動中的意義,離不開多學科相結合的方法及自然科學與社會科學的融通。

4 結語

近幾年理化分析技術測試手段不斷被應用于考古學科,擴寬了赭石等物質遺存研究的內涵,提高了考古研究工作的定性和定量化水平。除了對單個遺址的報道,關于赭石使用這一現象的綜合性匯總及系統性分析也顯得尤為關鍵。分析不同區域多個遺址內赭石歷時性使用情況的異同,為我們探討生態環境與生計模式、人口規模等文化元素互動的結果帶來了不同的視角。綜上所述,赭石考古的內容并不僅限于分析礦物成分、產地溯源及具體用途,其蘊含的行為信息對于闡釋史前人類的交流遷徙與文化發展規律等內容有重要意義。目前而言,中國境內舊石器時代赭石利用的證據較為有限,有待未來開展更多更深入、更系統的識別與研究,以全面解讀東亞地區赭石顏料開發策略的歷時性發展和區域性特征。

致謝:感謝日本東北大學林乃如、中國科學院地質與地球物理研究所沈中山博士、中國科學院古脊椎動物與古人類研究所岳健平博士、中國科學院古脊椎動物與古人類研究所侯亞梅研究員在文章寫作過程中進行的討論和提出的寶貴建議。

參考文獻

[1] Foley RA, Martin L, Lahr MM, et al. Major transitions in human evolution[J]. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B,2016, 371: 20150229

[2] Cornell RM, Schwertmann U. The iron oxides: structure, properties, reactions, occurrences and uses[M]. Wiley-VCH. 2003

[3] Nicola M, Mastrippolito C, Masic A. Iron Oxide-Based pigment and their use in history[A]. In Faivre D. Iron oxide: from nature to applications[C]. New Jersey: Wiley Press. 2016: 544-566

[4] Watts I, Chazan M, Wilkins J. Early evidence for brilliant ritualized display: specularite use in the Northern Cape (South Africa)between similar to 500 and similar to 300 Ka[J]. Current Anthropology, 2016, 57(3): 287-310

[5] Brooks AS, Yellen JE, Potts Richard, et al. Long-distance stone transport and pigment use in the earliest Middle Stone Age[J].Science, 2018, 360(6384): 90-94

[6] 楊石霞,許競文,浣發祥.古人類對赭石的利用行為在其演化中的意義[J]. 人類學學報,2022, 41(4): 649-658

[7] Barham LS. Systematic pigment use in the Middle Pleistocene of South-Central Africa[J]. Current Anthropology, 2002, 43(1): 181-190

[8] 周玉端,翟天民,李桓.舊石器時代人類對赭石的利用[J]. 江漢考古,2017(2): 43-51

[9] 申艷茹.中國舊石器時代遺址中赭石的功能[J]. 南方文物,2020(1): 187-192

[10] DErrico F, Moreno RC, Rifkin RF. Technological, elemental and colorimetric analysis of an engraved ochre fragment from the Middle Stone Age levels of Klasies River Cave 1, South Africa[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science, 2012, 39(4): 942-952

[11] Velliky EC, Porr M, Conard NJ. Ochre and pigment use at Hohle Fels cave: results of the first systematic review of ochre and ochre-related artefacts from the Upper Palaeolithic in Germany[J]. PLoS One, 2018, 13(12): e0209874

[12] D'Errico F, Pitarch Martí A, Wei Y. Zhoukoudian Upper Cave personal ornaments and ochre: rediscovery and reevaluation[J].Journal of human evolution, 2021, 161: 103088

[13] Wang FG, Yang SX, Ge JY, et al. Innovative ochre processing and tool use in China 40,000 years ago[J]. Nature, 2022, 603(7900): 284-289

[14] Marean CW, Bar-Matthews M, Bernatchez J, et al. Early human use of marine resources and pigment in South Africa during the Middle Pleistocene[J]. Nature, 2007, 449(7164): 905-908

[15] Cuenca-Solana D, Gutiérrez-Zugasti I, Ruiz-Redondo A, et al. Painting Altamira Cave? Shell tools for ochre-processing in the Upper Palaeolithic in northern Iberia[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science, 2016, 74: 135-151

[16] Pitarch Martí A, Zilh?o J, dErrico F, et al. The symbolic role of the underground world among Middle Paleolithic Neanderthals[J].Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 2021, 118: 33

[17] Bar-Yosef Mayer DE, Vandermeersch B, Bar-Yosef O. Shells and ochre in Middle Paleolithic Qafzeh Cave, Israel: indications for modern behavior[J]. Journal of Human Evolution, 2009, 56(3): 307-314

[18] Song YH, Cohen DJ, Shi JM. Diachronic change in the utilization of Ostrich Eggshell at the Late Paleolithic Shizitan Site, North China[J]. Frontiers in Earth Science, 2022

[19] Aldhouse-Green S, Pettitt P. Paviland Cave: contextualizing the ‘Red Lady[J]. Antiquity, 1998, 72(278): 756-772

[20] Trinkets E, Buzhilova AP. The death and burial of sunghir 1[J]. International Journal of Osteoarchaeology, 2010, 22(6): 655-666

[21] Vanhaeren M, dErrico F, Stringer C, et al. Middle Paleolithic shell beads in Israel and Algeria[J]. Science, 2006, 312(5781): 1785-1788

[22] Bouzouggar A, Barton N, Vanhaeren M, et al. 82,000-year-old shell beads from North Africa and implications for the origins of modern human behavior[J]. Anthropology, 2007, 104(24):9964-9969

[23] Wadley L, Hodgskiss T, Grant M. Implications for complex cognition from the hafting of tools with compound adhesives in the Middle Stone Age, South Africa[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 2009, 106(24): 9590-9594

[24] Wojcieszak M, Wadley L. Raman spectroscopy and scanning electron microscopy confirm ochre residues on 71000-year-old bifacial tools from Sibudu, South Africa[J]. Archaeometry, 2018, 60(5): 1062-1076

[25] Villa P, Pollarolo L, Degano I, et al. A milk and ochre paint mixture used 49,000 years ago at Sibudu, South Africa[J]. PLoS One,2015, 10(6): e0131273

[26] Zhang Y, Doyon L, Peng F, et al. An Upper Paleolithic perforated red deer canine with geometric engravings from QG10, Ningxia,Northwest China[J]. Frontiers in Earth Science, 2022, 10:814761

[27] Dayet L, dErrico F, García-Diez M, et al. Critical evaluation of in situ analyses for the characterisation of red pigments in rock paintings: a case study from El Castillo, Spain[J]. PLoS One, 2022, 17(1): e0262143

[28] Kurniawan R, Kadja GTM, Setiawan P, et al. Chemistry of prehistoric rock art pigments from the Indonesian island of Sulawesi[J].Microchemical Journal, 2019, 146: 227-233

[29] Dayet L, d Errico F, Garcia-Moreno R. Searching for consistencies in Ch?telperronian pigment use[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science, 2014, 44: 180-193

[30] Maryanti E, Ilmi MM, Nurdini N, et al. Hematite as unprecedented black rock art pigment in Jufri Cave, East Kalimantan,Indonesia: the microscopy, spectroscopy, and synchrotron X-ray-based investigation[J]. Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences, 2022, 14: 122

[31] Rifkin RF, Prinsloo LC, Dayet L, et al. Charaterising pigments on 30 000-year-old portable art from Apollo 11 Cave, Karas Region,southern Namibia[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports, 2016, 5: 336-347

[32] Gomes H, Martins AA, Nash G, et al. Pigment in western Iberian schematic rock art: An analytical approach[J]. Mediterranean Archaeology and Archaeometry, 2015, 15(1)

[33] Rigon C, Izzo FC, Pascual MLVD?, et al. New results in ancient Maya rituals researches: The study of human painted bones fragments from Calakmul archaeological site (Mexico)[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports, 2020, 32: 102418

[34] Hodgskiss T, Wadley L. How people used ochre at Rose Cottage Cave, South Africa: Sixty thousand years of evidence from the Middle Stone Age[J]. PLoS One, 2017, 12(4): e0176317

[35] Huntley J, Aubert M, Ross J, et al. One colour, (at least) two minerals: a study of mulberry rock art pigment and a mulberry pigment ‘quarry from the Kimberley, Northern Australia[J]. Archaeometry, 2015, 57(1): 77-99

[36] Behera PK, Thakur N. Late Middle Palaeolithic Red Ochre Use at Torajunga, an Open-Air Site in the Bargarh Upland, Odisha,India: Evidence for Long Distance Contact and Advanced Cognition[J]. Heritage: Journal of Multidisciplinary Studies in Archaeology, 2018, 6: 129-147

[37] Dayet L, Le Bourdonnec FX, Daniel F, et al. Ochre provenance and procurement strategies during the Middle Stone Age at Diepkloof Rock Shelter, South Africa[J]. Archaeometry, 2015, 58(5): 807-829

[38] Iriarte E, Foyo A, Sánchez MA, et al. The origin and geochemical characterization of red ochres from the Tito Bustillo and Monte Castillo Caves (Northern Spain) [J]. Archaeometry, 2009, 51(2): 231-251

[39] Moyo S, Mphuthi D, Cukrowska E, et al. Blombos Cave: Middle Stone Age ochre differentiation through FTIR, ICP OES, ED XRF and XRD[J]. Quaternary International, 2016, 404: 20-29

[40] Hovers E, Ilani Shimon, Bar-Yosef O, et al. An Early Case of Color Symbolism: Ochre Use by Modern Humans in Qafzeh Cave[J].Current Anthropology, 2003, 44(4): 491-522

[41] Dayet Bouillot L, Wurz S, Daniel F. Ochre resources, behavioural complexity and regional patterns in the Howiesons Poort: new insights from Klasies River main site, South Africa [J]. Journal of African Archaeology, 2017, 15(1): 20-41

[42] Velliky EC, MacDonald BL, Porr M, et al. First large-scale provenance study of pigments reveals new complex behavioural patterns during the Upper Palaeolithic of south-western Germany[J]. Archaeometry, 2021, 63(1): 173-193

[43] Cavallo G, Fontana F, Gonzato F, et al. Sourcing and processing of ochre during the late upper Palaeolithic at Tagliente rock-shelter (NE Italy) based on conventional X-ray powder diffraction analysis[J]. Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences, 2017, 9: 763-775

[44] Darchuk L, Tsybrii Z, Worobiec A, et al. Argentinean prehistoric pigments study by combined SEM/EDX and molecular spectroscopy[J]. Spectrochimica Acta Part A: Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy, 2010, 75(5): 1398-1402

[45] Charrié-Duhaut A, Porraz G, Cartwright C, et al. First molecular identification of a hafting adhesive in the Late Howiesons Poort at Diepkloof Rock Shelter (Western Cape, South Africa)[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science, 2012, 40(9): 3506-3518

[46] Dayet L, Texier PJ, Daniel F, et al. Ochre resources from the Middle Stone Age sequence of Diepkloof Rock Shelter, Western Cape,South Africa[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science, 2013, 40: 3492-3505

[47] Mortimore JL, Marshall LJR, Almond MJ, et al. Analysis of red and yellow ochre samples from Clearwell Caves and ?atalh?yük by vibrational spectroscopy and other techniques[J]. Spectrochimica Acta Part A Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy, 2004,60(5): 1179-1188

[48] Henshilwood CS, dErrico F, van Niekerk KL, et al. An abstract drawing from the 73,000-year-old levels at Blombos Cave, South Africa[J]. Nature, 2018, 562: 115-118

[49] DErrico F, Vanhaeren M, van Niekerk K, et al. Assessing the accidental versus deliberate colour modification of shell beads: a case study on perforated Nassarius kraussianus from Blombos Cave Middle Stone Age levels[J].. Archaeometry, 57(1): 51-76

[50] Henshilwood CS, dErrico F, van Niekerk KL, et al. A 100,000-year-old ochre-processing workshop at Blombos Cave, South Africa[J]. Science, 2011, 334(6053): 219-222

[51] Dayet L, Erasmus RM, Val A, et al. Beads, pigments and early Holocene ornamental traditions at Bushman Rock Shelter, South Africa[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports, 2017, 13(24): 635-651

[52] Langley MC, OConnor S, Piotto E. 42,000-year-old worked and pigment-stained Nautilus shell from Jerimalai (Timor-Leste):Evidence for an early coastal adaptation in ISEA[J]. Journal of Human Evolution, 2016, 97: 1-16

[53] Peresani M, Vanhaeren M, Quaggiotto E, et al. An Ochered Fossil Marine Shell From the Mousterian of Fumane Cave, Italy[J].PLoS One, 2013, 8(7): e68572

[54] Cortés-Sánchez M, Riquelme-Cantal JA, Simón-Vallejo MD, et al. Pre-Solutrean rock art in southernmost Europe: Evidence from Las Ventanas Cave (Andalusia, Spain) [J]. PLoS One 13(10): e0204651.

[55] Pitarch Martí A, Wei Y, Gao X, et al. The earliest evidence of coloured ornaments in China: The ochred ostrich eggshell beads from Shuidonggou Locality 2[J]. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology, 2017, 48(1): 102-113

[56] Li ZY, Doyon L, Li H, et al. Engraved bones from the archaic hominin site of Lingjing, Henan Province[J]. Antiquity, 2019,93(370): 886-900

[57] Pitarch Martí A, Zilh?o J, Mu?oz J R, et al. Geochemical characterization of the earliest Palaeolithic paintings from southwestern Europe: Ardales Cave, Spain[R]. The Art of Prehistoric Societies, VI Internacional Doctoral and Postdoctoral Meeting, 2019

[58] Ward I, Watchman A L, Cole N, et al. Identification of minerals in pigments from aboriginal rock art in the Laura and Kimberley regions, Australia[J]. Rock Art Research, 2001, 18(1): 15-23

[59] DErrico F, Salomon H, Vjgnaud C, et al. Pigments from the Middle Palaeolithic levels of Es-Skhul (Mount Carmel, Israel)[J].Journal of Archaeological Science, 2010, 37(12): 3099-3110

[60] Salomon H, Vignaud C, Lahlil S, et al. Solutrean and Magdalenian ferruginous rocks heat-treatment: acciental and/or deliberate action[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science, 2015, 55: 100-112

[61] Gialanella S, Belli R, Dalmeri G, et al. Artificial or natural origin of hematite-based red pigments in archaeological contexts: the case of Riparo Dalmeri(Ternto, Italy)[J]. Archaeometry, 2011, 53(5): 950-962

[62] Cavallo G, Fontana F, Gonzato F, et al. Textural, microstructural, and compositional characteristics of Fe-based geomaterials and Upper Paleolithic ocher in the Northeast Italy: implications for provenance studies[J]. Geoarchaeology, 2017, 32(4): 437-455

[63] Hunt A, Thomas P, James D, et al. The characterisation of pigments used in X-ray rock art at Dalakngalarr 1, central-western Arnhem Land[J]. Microchemical Journal, 2016, 126: 524-529

[64] De Faria DLA, Ven?ncio Silva S, de Oliveira MT. Raman microspectroscopy of some iron oxides and oxyhydroxides[J]. Journal of Raman Spectroscopy, 1997, 28(11): 873-878

[65] Bersani D, Lottici PP, Montenero A. Micro-Raman investigation of iron oxide films and powders produced by sol-gel syntheses[J].Journal of Raman Spectroscopy, 1999, 30(5): 355-360

[66] Needham A, Croft S, Kr?ger R, et al. The application of micro-Raman for the analysis of ochre artefacts from Mesolithic palaeolake Flixton[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports, 2018, 17: 650-656

[67] Stuart BH, Thomas PS. Pigment characterisation in Australian rock art: a review of modern instrumental methods of analysis[J].Heritage Science, 2017, 5: 10

[68] Wojcieszak M, Wadley L. A Raman micro-spectroscopy study of 77,000 to 71,000 year old ochre processing tools from Sibudu,KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa [J]. Heritage Science, 2019, 7: 24

[69] Texier PJ, Porraz G, Parkington J, et al. A Howiesons Poort tradition of engraving ostrich eggshell containers dated to 60,000 years ago at Diepkloof Rock Shelter, South Africa [J]. Anthropology, 2010, 107(14): 6180-6185

[70] Rosso DE, d Errico F, Queffelec A. Patterns of change and continuity in ochre use during the late Middle Stone Age of the Horn of Africa: The Porc-Epic Cave record [J]. PLoS One, 2017, 12(5): e0177298

[71] Lofrumento C, Ricci M, Bachechi L, et al. The first spectroscopic analysis of Ethiopian prehistoric rock painting[J]. Journal of Raman Spectroscopy, 2011, 43(6): 809-816

[72] 劉青松,鄧成龍,潘永信.磁鐵礦和磁赤鐵礦磁化率的溫度和頻率特性及其環境磁學意義[J]. 第四紀研究,2007, 27(6): 955-962

[73] Stacey FD, Banerjee SK. The physical principles of rock magnetism[M]. Amsterdam: Elsevier, 1974, 1-195

[74] Mooney SD, Geiss C, Smith MA. The use of mineral magnetic parameters to characterize archaeological ochres[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science, 2003, 30(5): 511-523

[75] McPherron SP. Lithics[M]. Richards MP, Britton K. Archaeological Science: an Introduction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 2020: 387-404

[76] 趙叢蒼.科技考古學概論[M]. 北京:高等教育出版社,2018: 291-359

[77] MacDonald BL, Hancock RGV, Cannon A, et al. Geochemical characterization of ochre from central coastal British Columbia,Canada[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science, 2011, 38(12): 3620-3630

[78] MacDonald BL, Hancock RGV, Cannon A, et al. Elemental analysis of ochre outcrops in southern British Columbia, Canada[J].Archaeometry, 2013, 55(6): 1020-1033

[79] Popelka-Filcoff RS, Robertson JD, Glascock MD, et al. Trace element characterization of ochre from geological sources[J]. Journal of Radioanalytical and Nuclear Chemistry, 2007, 272(1): 17-27

[80] Popelka-Filcoff RS, Miksa EJ, Robertson JD, et al. Elemental analysis and characterization of ochre sources from southern Arizona[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science, 2008, 35(3): 752-762

[81] 喬治 R,克里斯托弗 LH.地質考古學:地球科學方法在考古學中的應用[M]. 譯者:楊石霞,趙克良,李小強.北京:科學出版社, 2020

[82] 倫福儒 C,巴恩 P.考古學:理論方法與實踐[M]. 譯者:陳淳.第6 版.上海:上海古籍出版社,2015

[83] 王德滋,謝磊.光性礦物學[M]. 北京:科學出版社,2008: 1-26

[84] Erlandson JM, Robertson JD, Descantes C. Geochemical analysis of eight red ochres from western North America[J]. American Antiquity, 1999, 64(3): 517-526

[85] Jacobs Z, Roberts RG, Galbraith RF, et al. Ages for the Middle Stone Age of southern Africa: implications for human behavior and dispersal[J]. Science, 2008, 322(5902): 733-735

[86] Chase BM. South African palaeoenvironments during marine oxygen isotope stage 4: a context for the Howiesons Poort and Still Bay industries[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science, 2010, 37(6): 1359-1366

[87] Mackay A. Nature and significance of the Howiesons Poort to post-Howiesons Poort transition at Klein Kliphuis rockshelter, South Africa[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science, 2011, 38(7): 1430-1440

[88] Porraz G, Texier PJ, Archer W, et al. Technological successions in the Middle Stone Age sequence of Diepkloof Rock Shelter,Western Cape, South Africa[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science, 2013, 40(9): 3376-3400

[89] Tobias PV. From tools to symbols: from early hominids to modern humans[M]. In: dErrico F and Backwell L(eds). Johannesburg:Wits University Press, 2005

[90] Rifkin RF. The symbolic and functional exploitation of ochre during the South African Middle Stone Age[M]. Johannesburg: Wits University Press, 2013

[91] Wreschner EE, Bolton R, Butzer KW, et al. Red ochre and human evolution: a case for discussion[J]. Current Anthropology, 1980,21(5): 631-644

[92] Mcbrearty S, Brooks AS. The revolution that wasn't: a new interpretation of the origin of modern human behavior[J]. Journal of Human Evolution, 2000, 39(5): 453-563

[93] Keeley LH. Experimental determination of stone tool uses[M]. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1980

[94] Rifkin RF. Processing ochre in the Middle Stone Age: testing the inference of prehistoric behaviours from actualistically derived experimental data[J]. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology, 2012, 31(2): 174-195

[95] Hodgskiss T. Ochre use in the Middle Stone Age[J]. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Anthropology, 2020

[96] Kozowyk PRB, Langejans GHJ, Poulis JA. Lap Shear and impact testing of ochre and beeswax in experimental Middle Stone Age compound adhesives[J]. PLoS One, 2016, 11(3): e0150436

[97] Siddall R. Mineral pigments in archaeology: Their analysis and the range of available materials. Minerals, 2018, 8(5): 201

[98] Ismunandar, Nurdini N, Ilmi MM, et al. Investigation on the crystal structures of hematite pigments at different sintering temperatures[J]. Key Engineering Materials, 2021, 874: 20-27

[99] 靳桂云.土壤微形態分析及其在考古學中的應用[J]. 地球科學進展,1999, 14(2): 197-200

[100] 張海,莊奕杰,方燕明,等.河南禹州瓦店遺址龍山文化壕溝的土壤微形態分析[J]. 華夏考古,2016, 4: 86-95,I0009-I0014

[101] 魏屹,d'Errico F,高星.舊石器時代裝飾品研究:現狀與意義[J]. 人類學學報,2016, 35(1): 132-148

[102] Klein RG. Out of Africa and the evolution of human behavior[J]. Evolutionary Anthropology: Issues, News, and Reviews, 2008,17(6): 267-281

[103] 黃淑娉,龔佩華.文化人類學理論方法研究(第3 版)[M]. 廣州:廣東高等教育出版社,2004

[104] 莊孔韶.人類學通論[M]. 太原:山西教育出版社,2005

[105] Scott DA, Scheerer S, Reeves DJ. Technical examination of some rock art pigments and encrustations from the Chumash Indian site of San Emigdio, California[J]. Studies in Conservation, 2002, 47(3): 184-194

[106] DErrico F, Vanhaeren M. Evolution or Revolution? New evidence for the origin of symbolic behaviour in and out of Africa[M].Mellars P, Boyle K, Bar-Yosef O, et al. Rethinking the human revolution: new behavioural and biological perspectives on the origin and dispersal of modern humans[C]. Cambridge: McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, 2007: 257-286

[107] Wang C, Lu HY, Zhang JP, et al. Prehistoric demographic fluctuations in China inferred from radiocarbon data and their linkage with climate change over the past 50,000 years[J]. Quaternary Science Reviews, 2014, 98: 45-59

[108] Feng Y, Wang Y. The environmental and cultural contexts of early pottery in south China from the perspective of behavioral diversity in the Terminal Pleistocene[J]. Quaternary International, 2022, 608-609: 33-48

[109] Yang SX, Zhang YX, Li YQ, et al. Environmental change and raw material selection strategies at Taoshan: a terminal Late Pleistocene to Holocene site in north-eastern China[J]. Journal of Quaternary science, 2017, 32(5): 553-563

[110] Bae CJ, Douka K, Petraglia MD. On the origin of modern humans: Asian perspectives[J]. Science, 2017, 358(6368): eaai9067.

[111] Rifkin RF. Ethnographic insight into the prehistoric significance of red ochre[J]. Digging stick, 2015, 32(2): 7-10

[112] Huntley J. Australian Indigenous Ochres: Use, Sourcing, and Exchange[A]. In: Ian J, Bruno D(Eds). The Oxford Handbook of the Archaeology of Indigenous Australia and New Guinea[C]. Oxford University Press, 2018, 1-33

基金項目:自然科學基金項目(42177424);;中國科學院青年促進會研究項目(No. 2020074)