Transplanted kidney loss during colorectal cancer chemotherapy: A case report

Marta Pospiech, Aureliusz Kolonko, Teresa Nieszporek,Sylwia Kozak, Anna Kozaczka,Henryk Karkoszka,Mateusz Winder, Jerzy Chudek

Abstract

Key Words: Kidney transplantation; Colorectal cancer; Adjuvant chemotherapy; Graft loss; Complications; Case report

lNTRODUCTlON

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is one of the most common malignancies both in the general population[1] and in kidney transplant recipients (KTRs)[2,3]. The risk of CRC development is reported to be higher in transplant patients because of long-lasting exposure to immunosuppressive agents[4]. Although the patient survival rate for the KTR population with advanced CRC (stage III/IV) at the time of diagnosis is worse, mainly due to higher rates of recurrence, there was no significant difference in a 5-year patient survival in early cancer[5]. CRC in KTRs displays atypical characteristics in terms of tumor location, polyp size, and occurrence. The rate of ascending colon cancer is higher, whereas the rate of rectal cancer is lower in the transplant group[5,6]. Also, the number and size of polyps observed in preoperative colonoscopy are greater than in control patients. One of the possible causes of the poorer survival of KTRs with advanced cancer may be insufficient CRC treatment,i.e., tendency to less frequent use of adjuvant chemotherapy[5,6] because of concerns associated with incompatibility with immunosuppression regimen and the risk of deterioration of kidney graft function. The abovementioned obstacles preclude the formulation of clear guidelines for the management of CRC in KTRs.

Here, we present a patient with advanced colon cancer diagnosed 16 years after a successful kidney transplantation, presenting with an irreversible deterioration of kidney graft function shortly after the initiation of adjuvant CTH, to discuss the possible causes of kidney graft loss.

CASE PRESENTATlON

Chief complaints

A 36-year-old woman with a medical history of kidney transplantation in 2005, after recent right hemicolectomy due to locally advanced pT4AN1BM0(clinical stage III) colon adenocarcinoma (G2), was qualified (in March 2021) to adjuvant chemotherapy regimen based on oxaliplatin, leucovorin and 5-fluorouracil (FOLFOX-4). At that time, the kidney graft function was satisfactory; however, the slow increase in serum creatinine up to 1.4 mg/dL was observed during the few preceding months. The blood tests showed anemia (hemoglobin, 8.4 g/dL), C-reactive protein 11.2 mg/L, CA-125 18.7 U/mL, and CEA 0.95 ng/mL. After two FOLFOX-4 cycles, substantial deterioration of kidney graft function was observed, resulting in the discontinuation of chemotherapy and return to hemodialysis.

History of present illness

In October 2020 (16 years post-transplant), the patient started to report recurrent mild abdominal pain without concomitant hematochezia, diarrhea, change in bowel motility, or weight loss. At the same time, a slight increase in serum creatinine from 1.0 to 1.4 mg/dL [estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) 45 mL/min/1.73 m2], with no proteinuria, was detected. In January 2021, the patient was admitted to a surgery department with clinical suspicion of herniation of the terminal ileum into the cecum. During surgery, a large cecal tumor was found (7 cm × 5.5 cm × 5 cm), and a right hemicolectomy with terminal ileum-transverse colon graft was performed. Histological diagnosis was adenocarcinoma G2 invading the peritoneum and blood vessels, with metastases to two of 24 resected mesenteric lymph nodes (pT4AN1B) - corresponding to clinical stage III. A multidisciplinary team qualified the patient to adjuvant chemotherapy (FOLFOX-4), which was suspended due to abdominal wall abscess after the previous surgery. On March 17, 2021 (7 wk since hemicolectomy), the first FOLFOX-4 cycle was administered and the second was on April 1, 2021. However, the subsequent chemotherapy cycles were cancelled due to progressive kidney graft insufficiency. There was no deterioration of blood pressure control during CTH.

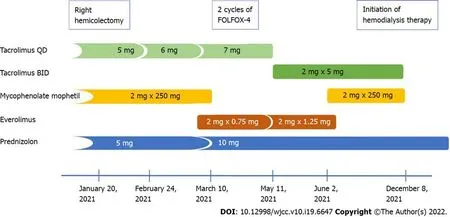

Meanwhile, immunosuppression was modified by conversion from mycophenolate mofetil 250 mg BID to everolimus 0.75 mg BID (Figure 1). Notably, during the subsequent 2 mo, the blood trough levels of everolimus were low (1.0-1.4 ng/mL). Finally, the drug was discontinued because of its poor gastric tolerance. In addition, the tacrolimus level started to fluctuate (with a nadir of 2.5 ng/mL), andde novoproteinuria was noticed up to 4.2 g/24 h. Lately, tacrolimus once daily was switched to twice daily formulation to achieve adequate blood trough levels. Serum creatinine level increased up to 3.4 mg/dL.

History of past illness

The patient was diagnosed with chronic glomerular nephritis at the age of 10 years. It was confirmed by kidney biopsy, and glucocorticoids and cyclophosphamide were initiated. In 2001, hepatitis C virus infection was diagnosed, and the patient underwent a successful 12-mo interferon-γ treatment. Hypertension was diagnosed at the age of 18 years in the course of chronic kidney disease. The patient developed end-stage kidney disease and started hemodialysis at the age of 19 years (2004). After 8 mo of dialysis therapy, the patient underwent kidney transplantation (2005) with basiliximab induction. The kidney graft function on an immunosuppressive regimen consisting of tacrolimus, mycophenolate mofetil and steroids was excellent, with serum creatinine of 1 mg/dL for many years. The immunosuppression schedule was modified between 4 and 8 years post-transplant by converting mycophenolate to azathioprine due to planned pregnancy. She passed two pregnancies, giving birth during 5 and 8 years post-transplant. During the whole observation, there were no episodes of acute kidney rejection or proteinuria. The blood trough levels of tacrolimus and mycophenolate mofetil were stable, at 6-7 ng/mL and 2.7 ng/mL, respectively.

Personal and family history

Family history was unremarkable.

Physical examination

Physical examination revealed no abnormalities except surgical scars.

Laboratory examinations

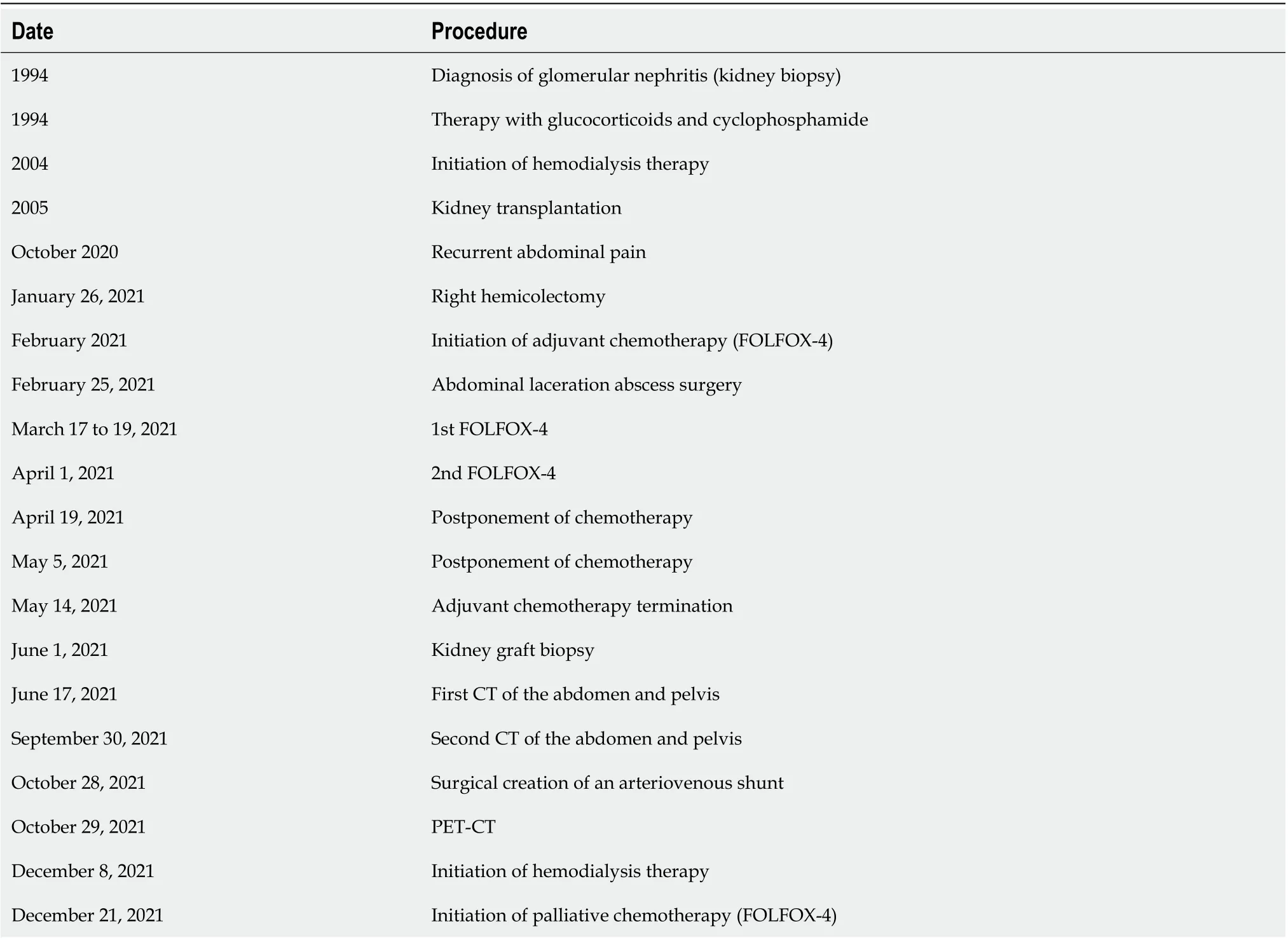

Because of the increase of serum creatinine up to 3.4 mg/dL, a kidney graft biopsy was performed on June 1, 2021. Histological examination revealed overlapping features of active chronic rejection and focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Overall, interstitial fibrosis and tubular atrophy covered > 50% of the interstitial area (Figure 2). Donor-specific antigens were not present, whereas a moderate Epstein-Barr viremia (7485 copies/mL) was detected. Other virological results (hepatitis B virus, hepatitis C virus and cytomegalovirus) were negative at that time.

Imaging examinations

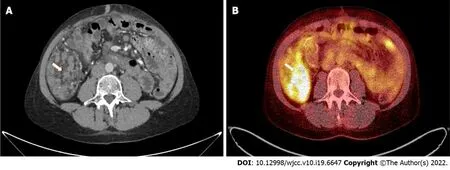

Computed tomography (CT) with contrast media administration was performed twice, during the oncological work-up, in June and September 2021. The second examination visualized intraperitoneal spread of colon adenocarcinoma, confirmed by positron emission tomography/CT (Figure 3), and corresponding with recent patient complaints about abdominal pain.

FlNAL DlAGNOSlS

Active chronic rejection of transplanted kidney with features of recurrent glomerulonephritis and further intraperitoneal spread of colon cancer was also diagnosed.

TREATMENT

Figure 1 Changes in the immunosuppression therapy after hemicolectomy and diagnosis of colon cancer.

Figure 2 Pathological findings in transplanted kidney biopsy. A and B: Glomerulus with segmental sclerosis - black arrow (A) - and reactive proliferation of podocytes around sclerosed segment - orange arrow (B); C and D: Area of tubular atrophy - black arrow - and compensative tubular hypertrophy - asterisks (C), with areas of interstitial fibrosis with infiltration of mononuclear cells - orange arrows (D); E-H: Immunohistochemistry showing focal interstitial infiltrates mainly composed of CD4-positive (E) and CD20-positive (G) cells, and diffuse interstitial infiltrates of CD8-positive (F) and CD68-positive (H) cells.

Hemodialysis therapy was initiated after creating an arteriovenous shunt when serum creatinine level exceeded 6 mg/dL. Before initiation of palliative chemotherapy,KRAS,NRASandBRAFgenotyping was performed. The analysis revealed mutation in codon 12 of the second exon (35 G>T) ofKRAS, denoting resistance to anti-epidermal growth factor receptor therapy. FOLFOX-4 regimen was chosen as the first-line palliative chemotherapy due to early discontinuation of this regimen in the adjuvant setting, frequent intestinal toxicity of irinotecan in hemodialysis patients, and restriction in the reimbursement of bevacizumab in patients with chronic kidney disease.

人群中有人小聲說,鐵冶楊細爹熟,那年他不是給風水先生帶過路么?聽到風水先生幾個字,我心里猛地一驚。塆里人都朝楊細爹看。楊細爹回頭掃了大家一眼,說鐵冶你們哪個不熟啊?要帶路你們帶去!他們舞槍弄棒的,我可不去!說著就往人群中退縮。

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

The patient remains under the care of an oncologist and nephrologist, continuing hemodialysis and palliative chemotherapy. The timeline of the information presented in this case report is shown in Table 1.

DlSCUSSlON

Cancer is the second most common cause of mortality and morbidity in KTRs after cardiovascular disease[7]. This increased cancer risk in the KTR population is driven mainly byde novocancers, with

Table 1 Timeline of diagnostic procedures and treatment

Figure 3 Pathological intraperitoneal infiltration (arrows) measuring 83 mm × 46 mm × 52 mm, with a standardized maximum uptake of 8.5 located in the right epigastric region, shown in computed tomography (A) and positron emission tomography (B) examinations.

CRC being the third most common cause of cancer death after non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma and lung cancer[8]. CRC in KTRs is reported to have a worse 5-year survival rate than in the general population[9,10], and develops more often at a younger age[9-11]. Even so, our patient was diagnosed with an advanced CRC at the age of 36 years. However, an analysis of Australia and New Zealand Dialysis and Transplant Registry Data revealed that cancer rates in KTRs are similar to those in nontransplanted subjects 20-30 years older[12]. Still, it is noteworthy that there were some additional risk factors for such an early development of cancer in the given patient, except for the post-transplant immunosuppression. Firstly, the primary kidney disease was glomerulonephritis treated with steroids and cyclophosphamide, whereas the pretransplant immunosuppressive treatment was shown to increase the cancer risk[12,13]. Secondly, the use of azathioprine could be an independent risk factor for advanced colorectal neoplasia in KTRs[14]. The patient has received this medication for 5 years because of the planned conception. Thirdly, unlike the virus-related malignancies such as Kaposi’s sarcoma and cervical cancer, CRC used to develop late in the post-transplant observation[3], as in our case.

Table 2 Clinical characteristics of kidney transplant patients treated with adjuvant (n = 7) and palliative chemotherapy (n = 5) for colorectal cancer

Nevertheless, when considering the undisputed tendency to the CRC development in younger KTRs in comparison to the general population, modified screening strategies were suggested in this specific cohort, including increased colonoscopy frequency[9] and early initial post-transplant colonoscopy within 2 years[10]. To date, KDIGO (Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes) Guidelines suggested that screening for CRC should be performed as recommended for the general population[15]. A cost-benefit ratio is another issue, as it was shown that eight colonoscopies were needed to identify one case of advanced neoplasia in KTRs cohort older than 50 years[16]. Although some authors suggested that screening colonoscopy in KTRs should be expanded to include recipients younger than 50 years[11] or even between the age of 35 and 50 years[17], such a policy would be cost-ineffective, in contrast to a screening program with fecal hemoglobin testing[17]. However, the latter measure is characterized by poor sensitivity but reasonable specificity. Besides, a fecal hemoglobin concentration can be used to stratify probability for the detection of advanced colorectal neoplasia in individuals with positive fecal immunochemical test[18].

In KTRs diagnosed with cancer, treatment includes conventional approaches based on surgery, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy[7]. Such a complex treatment, often complicated by adverse reactions, is effective, even in advanced CRC cases[19]. Although the administration of adjuvant chemotherapy is a current standard of care in stage III colon cancer, the complication risk of such therapy is strongly recommended to be assessed, especially among patients with pre-existing kidney dysfunction[1]. The data concerning adjuvant and palliative chemotherapy and their outcomes in KTRs are limited (Table 2). Some advanced stage transplant patients did not receive adequate chemotherapy because of the concern of drug-drug interactions with the immunosuppressive regimen[20]. Despite that oxaliplatin and 5-fluorouracil are partly excreted in urine, the renal toxicity potential of anti-CRC drugs is low, except forde novoproteinuria and arterial thromboembolic events observed during bevacizumab therapy[20]. Nevertheless, oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy is neither nephrotoxic[21] nor interferes with blood levels of immunosuppressants[20]. However, it has been reported that repeated cycles of oxaliplatin in patients with prior renal impairment may cause deterioration of kidney function[22]. In our case, the kidney graft function before FOLFOX-4 initiation was already impaired (eGFR 45 mL/min/1.73 m2), but it rapidly deteriorated during the first 2 mo of therapy. However, it might have been caused by active chronic rejection coexisting with recurrent glomerulonephritis, which probably started earlier, as indicated by the previously slowly increasing serum creatinine concentration. Moreover, both processes mentioned above might be accelerated by decreasing net immunosuppression strength caused by modification of the immunosuppressive regimen and impaired drug absorption after hemicolectomy. Nevertheless, although reducing immunosuppression treatment with or without conversion to mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitor is suggested in KDIGO guidelines[15] and the literature[7,23], the risk of graft rejection and loss is not to be disregarded.

CONCLUSlON

Several risk factors, including long-lasting immunosuppression, may contribute to CRC development in KTRs at a younger age. We acknowledge the risk of rapid kidney graft loss, which occurred during the initiation of adjuvant chemotherapy for colon cancer, but it may rather be a consequence of underimmunosuppression due to both impaired drug absorption and treatment changes driven by the cancer diagnosis. Hence, any modification of immunosuppressive regimen in newly diagnosed cancer patients should be carefully considered to balance the potential risks and benefits, bearing in mind the kidney graft function.

FOOTNOTES

lnformed consent statement:Informed written consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this report and any accompanying images.

Conflict-of-interest statement:The authors declare no conflict of interest.

CARE Checklist (2016) statement:The authors have read the CARE Checklist (2016), and the manuscript was prepared and revised according to the CARE Checklist (2016).

Open-Access:This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BYNC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is noncommercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Country/Territory of origin:Poland

ORClD number:Marta Po?piech 0000-0003-4417-5518; Aureliusz Kolonko 0000-0002-9647-1872; Teresa Nieszporek 0000-0001-6249-7153; Sylwia Kozak 0000-0002-5226-5006; Anna Kozaczka 0000-0001-5255-3107; Henryk Karkoszka 0000-0001-5479-0165; Mateusz Winder 0000-0003-3175-5660; Jerzy Chudek 0000-0002-6367-7794.

S-Editor:Fan JR

L-Editor:Kerr C

P-Editor:Fan JR

World Journal of Clinical Cases2022年19期

World Journal of Clinical Cases2022年19期

- World Journal of Clinical Cases的其它文章

- Hem-o-lok clip migration to the common bile duct after laparoscopic common bile duct exploration: A case report

- Preliminary evidence in treatment of eosinophilic gastroenteritis in children: A case series

- Identification of risk factors for surgical site infection after type II and type III tibial pilon fracture surgery

- Sustained dialysis with misplaced peritoneal dialysis catheter outside peritoneum: A case report

- Delayed-onset endophthalmitis associated with Achromobacter species developed in acute form several months after cataract surgery: Three case reports

- Diagnostic accuracy of ≥ 16-slice spiral computed tomography for local staging of colon cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis