聯合多源多時相衛星影像和支持向量機的小麥白粉病監測方法

趙晉陵 杜世州 黃林生

摘要:白粉病主要侵染小麥葉部,可利用衛星遙感技術進行大范圍監測和評估。本研究利用多源多時相衛星遙感影像監測小麥白粉病并提升分類精度。使用四景 Landat-8的熱紅外傳感器數據(Thermal Infrared Sensor ,TIRS )和20景 MODIS 影像的 MOD11A1溫度產品反演地表溫度(Land Surface Temperature , LST ),使用4景國產高分一號( GF-1) 寬幅相機數據(Wide Field of View ,WFV )提取小麥種植區和計算植被指數。首先,利用ReliefF算法優選對小麥白粉病敏感的植被指數,然后利用時空自適應反射率融合模型(Spa? tial and Temporal Adaptive Reflectance Fusion Model ,STARFM )對 Landsat-8 LST 和 MOD11A1數據進行時空融合。利用 Z-score 標準化方法對植被指數和溫度數據統一量度。最后,將處理和融合后的單一時項 Landsat-8 LST 、多時相 Landsat-8 LST 、累加 MODIS LST 和多時相Landsat-8 LST 與累加 MODIS LST 結合的數據分別輸入支持向量機(Support Vector Machine , SVM )構建了四個分類模型,即 LST-SVM 、SLST-SVM 、MLST- SVM 和 SMLST-SVM ,利用用戶精度、生產者精度、總體精度和 Kappa 系數對比四個模型的分類精度。結果顯示,本研究構建的 SMLST-SVM 取得了最高分類精度,總體精度和 Kappa 系數分別為81.2%和0.67,而 SLST-SVM 則為76.8%和0.59。表明多源多時相的 LST 聯合 SVM 能夠提升小麥白粉病的識別精度。

關鍵詞:小麥白粉病;高分一號;MODIS ;Landsat-8;地表溫度;支持向量機

Monitoring Wheat Powdery Mildew (Blumeriagraminis f. sp. tritici) Using Multisource and Multitemporal SatelliteImages and Support Vector Machine Classifier

ZHAO Jinling1 , DU Shizhou2* , HUANG Linsheng1

(1. National Engineering Research Centerfor Analysis and Application of Agro-Ecological Big Data, Anhui Univer‐sity, Hefei 230601, China;2. Institute of Crops, Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Hefei 230031, China )

Abstract: Since powdery mildew (Blumeriagraminis f. sp. tritici) mainly infects the foliar of wheat, satellite remote sensing technology can be used to monitor and assess it on a large scale. In this study, multisource and multitempo‐ral satellite images were used to monitor the disease and improve the classification accuracy. Specifically, four Land‐ sat-8 thermal infrared sensor (TIRS) and twenty MODerate-resolution imaging spectroradiometer (MODIS) temper‐ature product (MOD11A1) were used to retrieve the land surface temperature (LST), and four Chinese Gaofen-1(GF-1) wide field of view (WFV) images was used to identify the wheat-growing areas and calculate the vegetation indices (VIs). ReliefF algorithm was first used to optimally select the vegetation index (VIs) sensitive to wheat pow ‐dery mildew, spatial-temporal fusion between Landsat-8 LST and MOD11A1 data was performed using the spatial and temporal adaptive reflectance fusion model (STARFM). The Z-score standardization method was then used to unify the VIs and LST data. Four monitoring models were then constructed through a single Landsat-8 LST, multi‐ temporal Landsat-8 LSTs (SLST), cumulative MODIS LST (MLST) and the combination of cumulative Landsat-8 and MODIS LST (SMLST) using the Support Vector Machine (SVM) classifier, that were LST-SVM, SLST-SVM, MLST-SVM and SMLST-SVM. Four assessment indicators including user accuracy, producer accuracy, overall ac‐ curacy and Kappa coefficient were used to compare the four models. The results showed that, the proposed SMLST- SVM obtained the best identification accuracies. The overall accuracy and Kappa coefficient of the SMLST-SVM model had the highest values of 81.2% and 0.67, respectively, while they were respectively 76.8% and 0.59 for the SLST-SVM model. Consequently, multisource and multitemporal LSTs can considerably improve the differentiation accuracies of wheat powdery mildew.

Key words: wheat powdery mildew; GF-1; MODIS; Landsat-8; land surface temperature; support vector machine

CLC number:S435.121.4;TP79?????????????? Documents code:A????????? Article ID:SA202202009

Citation:ZHAO Jinling, DU Shizhou, HUANG Linsheng. Monitoring wheat powdery mildew (Blumeriagraminis f. sp. tritici) using multisource and multitemporal satellite images and support vector machine classifier[J]. Smart Agri‐ culture, 2022, 4(1):17-28.(in English with Chinese abstract)

趙晉陵, 杜世州, 黃林生.聯合多源多時相衛星影像和支持向量機的小麥白粉病監測方法[J].智慧農業(中英文), 2022, 4(1):17-28.

1? Introduction

Powdery mildew (Blumeriagraminis f. sp. trit‐ici) can occur at all stages of the wheat growth. It is a serious disease in some provinces of China, such as Sichuan, Guizhou, and Yunnan[1]. In recent years, it has become more severe in the wheat-growing ar‐eas of Northeastern China, North China, and North ‐ western China. When infected by the disease, some serious results will be caused such as early wither‐ing of leaves, decrease of panicle number, and de‐ crease of 1000-grain weight. Generally, the disease can lead to a 5%-10% reduction in yield and when it is seriously infected, a more serious loss of more than 20% can occur[2]. In view of the harmful effects on wheat production caused by the wheat powdery mildew,? it? is? of great? significance? to? improve? the monitoring efficiency and accuracy. However, it is difficult for traditional in-situ sampling and random investigation? methods? to? meet the needs? of large- scale monitoring due to the limitations in terms of timeliness,? economy,? and? accuracy[3]. Fortunately, the? modern? information? technology? has? facilitated the accurate and efficient identification of crop dis‐ eases to ensure food security[4–6].

In? recent? years,? the? development? of? remote sensing? technology? has? provided? an? important means? for? monitoring? and? forecasting? large-scale wheat diseases and insect pests. It obtains crop in ‐ formation quickly, accurately and objectively. Many scholars have? studied remote? sensing-based? moni‐toring of wheat diseases and insect pests by using ground-based, airborne and spaceborne remote sens‐ing data. For example, Huang et al.[7] showed that the? photochemical? reflectance? index (PRI) was strongly correlated with wheat yellow rust and the coefficient? of determination (R2) could? reach 0.97 for the PRI-based monitoring model. Zhang et al.[8] built a discriminant model for wheat powdery mil‐dew? severities? by? introducing? continuous? waveletanalysis based on the leaf-scale hyperspectral data.Luo? et? al.[9]? constructed? a? monitoring? model? ofwheat? aphid? in? two-dimensional? feature? space? de‐rived from the modified normalized difference wa‐ter? index (MNDWI) and? land? surface? temperature(LST) based on Landsat-5 TM imagery, which hada high discriminant precision. Zheng et al.[10] con ‐structed a red edge disease stress index (REDSI) us‐ing? three? red-edge? bands? from? Sentinel-2 satelliteimagery? for? monitoring? the? stripe? rust? on? winterwheat and got a satisfying result. The above studiesshowed that the spaceborne remote sensing imageshave greatly facilitated the monitoring and diagno‐sis of wheat diseases.

In previous? studies, multispectral satellite im‐ages were adopted to investigate the large-scale dis‐ease occurrence. Since the rapid development of hy‐perspectral remote sensing technology, some studieson wheat powdery mildew had been explored usingthe? hyperspectral? data. More? vegetation? indiceswere derived from the hundreds of spectral bands ofhyperspectral data. He et al.[11] improved the moni‐toring accuracy of wheat powdery mildew severityby selecting suitable observation angles and devel‐oping a novel vegetation index (VI). Zhao et al.[12]identified the powdery mildew? severities of wheatleaves? quantitatively? on? hyperspectral? images? andimage? segmentation techniques. Khan? et? al.[13]? de‐tected the disease using a partial least-squares lineardiscrimination? analysis? and? the ?combined? optimalfeatures (i. e., normalized difference texture indices(NDTIs) and VIs).

It? can? be? found? that? the? disease? monitoringmainly depends on the vegetation changes betweenhealthy and diseased wheat. Nevertheless, the com ‐mission and omission errors are usually caused dueto? the? influences? of? other? stress? types? such? asdrought,? inadequate? nutrition,? and? other? diseases. The? incidence? of? wheat? powdery? mildew? is? in ‐ volved in several affecting factors such as tempera‐ture, humidity and planting system. Considering the availability of temperature data of satellite images for large-scale monitoring, in this? study, particular attention was? given to the? contribution? of LST to the disease occurrence. As a key habitat factor, LST was included in the construction of monitoring mod‐el for the disease. LST remote sensing image was usually used in the previous monitoring of the dis‐ ease[14] , but it has a cumulative effect on wheat pow ‐dery mildew. A single-phase LST image cannot ac‐curately represent the disease occurrence condition during the whole growth period. The primary objec‐tive of this study was to explore the availability and feasibility to identify wheat powdery mildew using a? combination? of? multisource? and? multitemporal spaceborne remote? sensing? imagery. More? specifi‐cally, three types of satellite images were adopted to identify? the? wheat-planting? areas? and? retrieve? the LST. Single and multitemporal LSTs were input in ‐ to? the? support vector machine (SVM) to? compare the monitoring effects.

2? Materials and methods

2.1 Study area

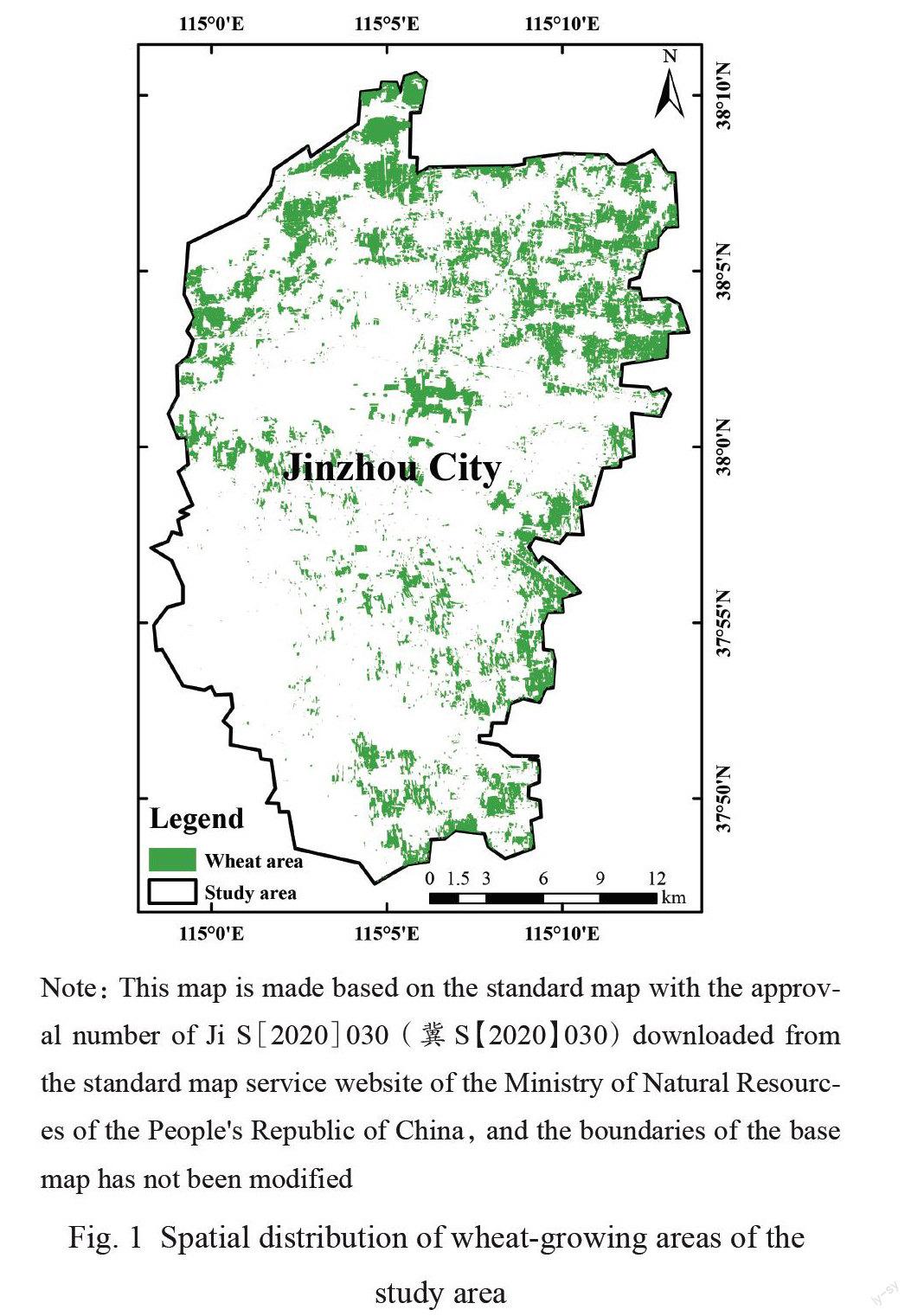

The study area is located in Jinzhou City, He‐bei province, China (114.97°-115.20° E, 37.80°-38.17° N)(Fig.1). It has a warm-temperate conti‐nental monsoon? climate, with? a? flat? and? open ter‐ rain. There is a significant seasonal variation of sun radiation. Wheat is one of the important grain crops and widely planted in this area. The critical periods of wheat growth range from April to May. Due to its? flat? terrain,? appropriate? climate? conditions? and relatively? single? planting? structure,? the? region? issuitable for studying wheat powdery mildew usingremote sensing technology[15]. The historic statisticaldata? also? show? that? the? occurrence? frequency? ofwheat powdery mildew is high and hazard degree isserious[16]. The wheat-planting areas were extractedby combining the elevation data and reflectance ofthe near-infrared (NIR) band of Chinese Gaofen-1(GF-1) by? using? decision? tree? classification? tech ‐niques (Fig.1(b)). The extraction results were com ‐pared with the statistical data of Shijiazhuang City,which could fulfill the accuracy requirement of re‐mote sensing-based crop extraction.

2.2 Data collection and pre-processing

The data used in this study mainly were space‐borne remote sensing images and field survey dataof wheat powdery mildew. In-situ experiments werecarried out on 27 and 28 May 2014 in the central ar‐eas of Jinzhou City. Several typical experimental re‐gions were selected to collect the ground-truth data, where wheat was widely planted? and wheat pow ‐dery mildew occurs frequently. A total of 69 valid data were acquired using the method presented by Yuan et al.[17]. The wheat powdery mildew severities were? specified? according? to? the? Rules? for? the? in ‐vestigation and forecast of wheat powdery mildew [B. graminis (DC.) Speer](NY/T 613-2002). First‐ly,? the? average? severity? D? of diseased? leaves? for the? colony? leaves? was? calculated? according? to Equation (1). Then, the disease index I could be de‐ rived from Equation (2). The five levels were final‐ly? obtained? according? to? Table 1. To? increase? the comparability of remote sensing-based disease mon‐itoring, the five levels of severities were further di‐ vided into three levels of 0(healthy), 1(mild) and 2(severe).

where di? is the value of eight severity levels, which is 1%, 5%, 10%, 20%, 40%, 60%, 80%, 100%; li? is the number of diseased leaves for each level; L is the total number of investigated diseased leaves.

where F is the percentage of diseased leaf, which is ratio between the diseased leaves and total investi‐ gated leaves.

Multisource? remote? sensing? data? were? com ‐ posed of GF-1, Landsat-8 and MODerate-resolution imaging spectroradio-meter (MODIS) data products.

GF-1: Four scenes of GF-1 wide field of view (WFV) images were collected on 6, 17 and 26 May, and 7 June 2014,? respectively,? with? the? path/rownumbers of 3/93 and 4/92. There are four spectralbands for the GF-1 WFV sensor within the spectralrange of 0.45-0.89μm, with the spatial resolutionof 16 m. The primary preprocessing procedures wereperformed? including? orthorectification,? radiationcalibration, atmospheric correction and image sub ‐setting. The radiation brightness (Le , W/(m2·sr ·μm))of a WFV image can be derived from Equation (3).

where DN is the digital number of pixel. The abso‐lute? radiometric? calibration? coefficients (gain? andoffset) were derived from the China Center for Re‐sources Satellite Data and Application (http://www.cresda. com/CN/). After? finishing? the? radiometriccalibration,? the? Fast? Line-of-Sight? AtmosphericAnalysis of Spectral Hypercubes (FLAASH) mod‐ule in ENVI 5.3 software was used to complete theatmospheric? correction. The? geometric? correctionwas carried out using the second-order polynomialmodel with the accuracy of less than a pixel.

Landsat-8: The Landsat-8 operational land im‐ager (OLI) data were used to estimate the land re‐flectance and the thermal infrared sensor (TIRS) da‐ta were used for retrieving the LST[18]. Four scenesof cloud-free images were selected and their acquisi‐tion date was 4 April, 23 April, 15 May and 22 May2014, respectively. They were preprocessed includ‐ing accurate geometric correction and radiation cor‐rection.

MOD11A1 product: It provided daily per-pix ‐el? land? surface? temperature? and? emissivity(LST&E) with 1 km spatial resolution[19]. A total of20 images were? obtained? from? the? land processesdistributed active archive center (LPDAAC) from 1April to 27 May, 2014. The data were preprocessedusing the MRT (MODIS Reprojection Tool).

2.3 Selection of vegetation indices

A total of eight VIs suitable for monitoring thewheat powdery mildew were selected in this studybased on the previous studies (Table 2).

To find out the most sensitive features, the Re‐liefF? algorithm was used? due to? its? advantages? of dealing with multi-class classification problem and having no restrictions on the data types. A sample R was? randomly? taken? from? the? training? sample? set each? time,? and? then? k? nearest? neighbor? samples (near Hits) of R were found from the sample set of the same class as R, and k nearest neighbor samples (near Misses) were found from each sample set of different? classes? of? R. The? input? features? were ranked according to the weights from large to small. Then? the? correlation? analysis? was? carried? out? for each feature and the combination with the smallest correlation coefficient was selected as the best com ‐ bination? for? model? construction. The? superiority and efficiency have been illustrated in remote sens‐ing-based? classification? and? object recognition[20-23]. Consequently, it was adopted to perform the feature selection, which gave different weights to the fea‐tures in terms of the correlations between features and various disease samples[24]. Specifically, accord‐ing? to? the? ReliefF? algorithm,? all? the? VI? variables were? sorted? in? descending? order? of? weight,? and eight VIs were selected with the weight of 0.075 as the threshold value. Then, the? correlation ?analysisamong the selected features were conducted. Whenthe correlation coefficient (r) of the feature owingthe highest weight that was greater than 0.9, it waseliminated,? and? then? that? of? the? second? highestweight with a high r was eliminated, and so on. Inaddition, there was a close relationship between thedisease? incidence? and? meteorological? factors? suchas? temperature,? precipitation,? humidity,? etc. Thechanges of VIs calculated at different growth stagesalso affected the sensitivity to the disease. Consider‐ing the temporal features and accumulative effect oftemperature, three VIs were finally selected, namelythe SAVI on 26 May 2014 and the SIPI and EVI on17 May 2014.

2.4 Estimation of LST

Two-channel? nonlinear? splitter? algorithm? wasadopted to increase the information amount and re‐duce the influence of errors. The equation is shownas (12).

where ε and Δε respectively? represents? the? meanand difference values of the two channels ′emissivi- ties depending on the land type and coverage; Ti? and Tj? are the? observed brightness temperatures? of the two channels; bi (i =0, 1, 2, … , 7) is the simulation dataset of various coefficients which can be derived from? laboratory? data,? atmospheric? parameters? and the atmospheric radiation transmission equation. In order to modify the calculation precision, the coeffi- cient depends on the atmospheric water vapour col- umn[33]. Fig.2 is the LST of 22 May 2014 retrieved from Landsat-8 TIRS image. In general, the LSTs of crop planting areas are lower than other regions. To calculate the land surface emissivity, the weight- ing? method? of vegetation? coverage? was? adopted, which bases on the NDVI and vegetation coverageretrieved from the visible and NIR bands of Land- sat-8 imagery [34].

The? occurrence? and? development? of? wheat powdery mildew is a relatively long process during which the LST has a significant cumulative effect.For example, temperature conditions which are fa-vorable for wheat powdery mildew infection in ear-ly April will aggravate the disease. As a result, thedisease? at? the? end? of May? has? a? high? correlationwith previous LST. The Landsat-8 LST data at fourgrowth stages were selected including the standingstage, jointing? stage,? flowering? stage? and? milkingstage, for the retrieval of LST and their summationSLST is shown in Equation (13).

where SLST denotes the cumulative effect of multi-temporal? Landsat-8 LST? data; LST? is? calculatedfrom a single Landsat-8 TIRS image; i (1, 2, 3, 4)represents the four stages, and the 20 means the up-per limit of temperature suitable for the incidence ofwheat? powdery? mildew. Similarly,? the? summationof 20 MOD11A1(MLST) can be also obtained ac-cording to the Equation (14).

2.5 Spatial-temporal fusion of MOD11A1and Landsat-8 LST

Since the four Landsat-8 LST data cannot fullyreflect the variation trend of LST during the wholewheat growth, the daily MOD11A1 was introduced.In order to obtain a data sequence that have enoughspatial and temporal resolutions, the widely appliedspatial? and? temporal? adaptive? reflectance? fusionmodel (STARFM)[35] was used to conduct the spa-tial-temporal? fusion? of? Landsat-8? LST? andMOD11A1. The algorithm ignores the spatial posi-tion registration and atmospheric correction errors,so the pixel values of low spatial resolution (LSR)remote sensing data at the moment t can be calculat-ed using the weighted? sum? of that of high? spatialresolution (HSR) data (Equation (15)).

Ct =∑( Fti× A t(i))????????????????? (15)

where Fti? is the pixel value of HSR data for the posi‐tioni at the time t; A t(i) shows the weight of coverage area for each pixel; Ct? represents the pixel value of LSR data at the corresponding time.

The? STARFM? algorithm? first? obtains? the MOD11A1 and Landsat-8 LST data and their devia‐tion at the time tk . The deviation is caused by the systematic? errors? and? land? cover? changes. Mean ‐ while, the? Landsat-8 LST? of the time? t0? in? accor‐ dance with MOD11A1 were predicted. The devia‐tion remains constant as time changes was assumed, and the pixel values of Landsat-8 LST at the time t0 are Equation (16).

HSR ( xi,yi,t0)= LSR ( xi,yi,t0)+

HSR ( xi,yi,tk )- LSR ( xi,yi,tk )??? (16)

Considering the edge effect of pixels, a cloud- free? pixel? was? selected? in? the? moving? window which was similar to the spectrum of central pixel when the pixel value was calculated. The calculat‐ing? the? central? pixel? value? is? shown? as? Equa‐tion (17).

HSR ( xw/2,yw/2,t0)=

Wijk×( LSR ( xi,yi,t0)+

HSR ( xi,yi,tk )- LSR ( xi,yi,tk ))? ( 17)

where? w? is? the? size? of? the? moving? window;( xw/2 , yw/2) represents? the? position? of central? pixel; Wijk? denotes the weight coefficient of a pixel similar to? the? central pixel. The? spectral? distance? weight, temporal? distance? weight,? and? spatial? distance weight of a similar pixel were obtained in the win ‐dow by a normalization method. The three weight coefficients were taken by referring to the study of Gao? et? al. in 2006[35]. Four? Landsat-8 LST (LSTi) and 20 MOD11A1(LSTj) were used for the spatial- temporal? fusion. The? fusion? data? sequences? were summed up as the SMLST in Equation (18).

SMLST = LSTi + LSTj?????????????????? ( 18)

2.6 Construction of monitoring models

Support vector machine (SVM) has the advan‐tages? of? a? simple? structure,? strong? generalizationability,? and high? accuracy, which has been widelyused? in the? classification? of remote? sensing? imag‐es[36]. The? discriminant? function? of? the? model? isshown as Equation (19).

f ( x)= sgn (x ai yi k ( xi,x)+ b)

where ai? is the Lagrange multiplier; Sv? is the supportvector; xi? and yi? represent two kinds of support vec‐tors; b is the threshold; k(xi , x) represents a positivedefinite kernel function which satisfies the Mercertheorem.

The? Z-score? method? was? used? to? standardizeVIs and temperature data according to Equation (20)due to their different units. The training and valida‐tion? datasets? were? divided? using? the? ratio? of 7:3.Four? SVM-based models (LST-SVM,? SLST-SVM,MLST-SVM and SMLST-SVM) were trained usingthe optimally selected three VIs. In addition to theVIs, these models were also involved in the Land‐sat-8 LST on 22 May (LST), four cumulative Land‐sat-8 LST data (SLST), 20 cumulative MOD11A1(MLST) and? cumulative? spatial-temporal? fusionLST? combing? Landsat-8 LST? and? MOD11A1(SMLST), respectively. These models will explore abetter? application? of remote? sensing-based LST tothe monitoring of wheat powdery mildew.

x '=(x -μ)ρ????????????????????? (20)

where x ' is the standardized data;μ is the mean oforiginal data;ρ is the standard deviation.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Validation of the monitoring results

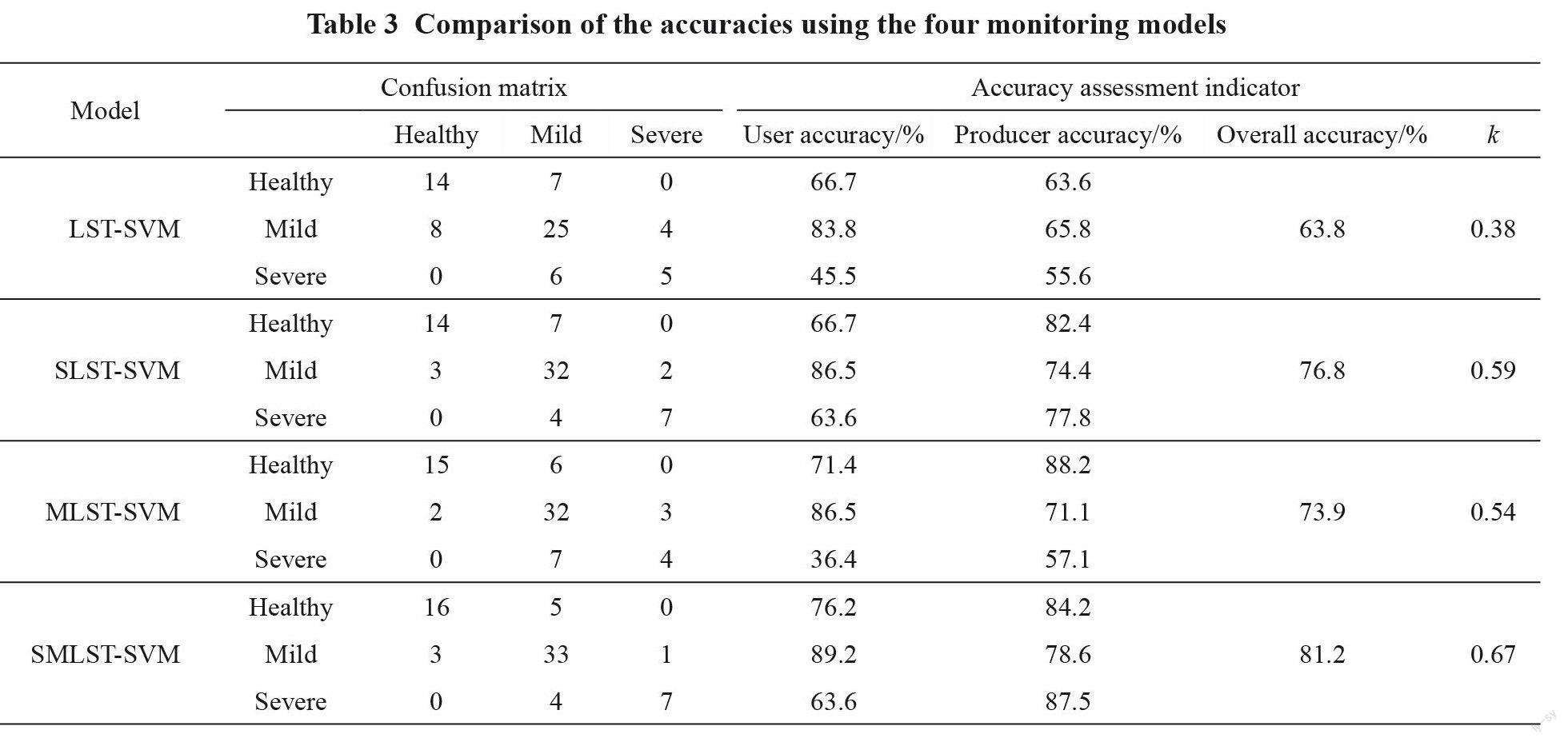

The? cross-validation? was? adopted? to? estimatethe? monitoring? accuracies. As? shown? in? Table 3,four indicators, namely the user accuracy (UA), pro ‐ducer? accuracy (PA),? overall? accuracy (OA) and Kappa coefficient (k) were used to assess the four SVM-based models. It could be seen that the SLST- SVM and SMLST-SVM achieved better classifica‐tion? performance. In? terms ?of? OA,? the? SMLST- SVM? model? obtained the best result,? followed by the SLST-SVM and MLST-SVM models, while the LST-SVM model got the lowest value. The OAs of models indicated that the LST had a cumulative ef‐fect on the wheat powdery mildew infection. The k values? of? SMLST-SVM,? MLST-SVM? SLST-SVM and LST-SVM were 0.67, 0.54, 0.59 and 0.38, re‐spectively, which also showed the similar trend withOAs. From the perspective of UA, the ability of thefour? models? to? distinguish? diseased? and? healthywheat? was? strong. The? differentiation? ability? ofSLST-SVM and SMLST-SVM models for mild andsevere? wheat? powdery? mildew? were? significantlyhigher than that? of LST-SVM model. The? accura‐cies of MLST-SVM model were slightly lower thanthose? of? SLST-SVM? and? SMLST-SVM? models,mainly? due? to? the? low? spatial? resolution? ofMOD11A1 data on the city scale. The above resultsshow that the introduction of multi-temporal and cu ‐mulative LST can effectively improve the monitor‐ing and identification of wheat powdery mildew se‐verities.

Huang et al.[37] identified wheat powdery mil‐ dew? of the? study? area using 30 m-resolution? Chi‐nese HJ-1A/1B data to inverse LST and extract four-band reflectance data and build seven VIs. A combi‐ nation? method (GaborSVM) of? SVM? and? Gabor wavelet features were proposed to obtain the OA of 86.7% that was higher than 81.2% of this study, but the OA of SVM-based method was 80% and lower than this study. The primary reason is that the spa‐tial resolution of HJ-1B IRS is 300 m, but it is just 1000 m? for? MOD11A1. The? comparison? studyshows that spatial resolution of optical and thermalinfrared satellite remote sensing images is an impor‐tant factor of affect the accuracy of wheat powderymildew.

3.2 Mapping of wheat powdery mildew

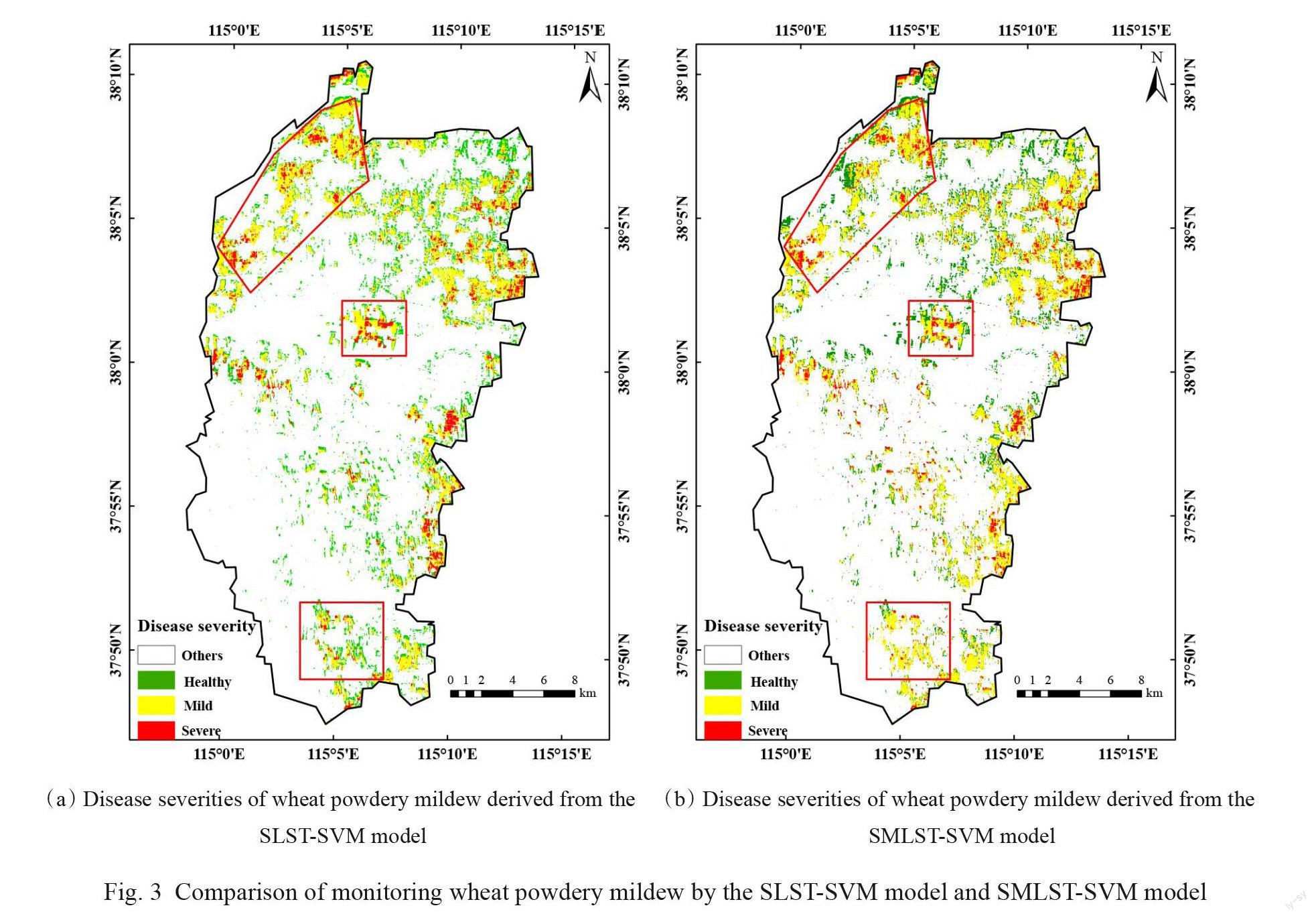

Based on multisource and multitemporal Land‐sat-8, GF-1 and MODIS data, three VIs of SIPI, SA ‐VI and EVI were optimally selected by the ReliefFalgorithm? and? correlation? analysis. The? VIs? andfour? temperature? data? of LST,? SLST,? MLST? andSMLST? were? respectively? used? to? construct? four monitoring? models? through? the? SVM,? namely? the LST-SVM,? SLST-SVM, MLST-SVM? and? SMLST- SVM. For example, the severity distribution on 26 May 2014 in Jinzhou was shown in Fig.3 using the SLST-SVM and SMLST-SVM models. The overall spatial distribution of wheat powdery mildew usingthe two monitoring models were similar. Neverthe‐less,? there? were? also? some? obvious? differences? asshown in the red boxes. It was more serious in theeastern part than in the western part of the study ar‐ea. It was also obvious that the wheat powdery mil‐dew mainly occurred in the areas where wheat waswidely planted.

In the? central regions where the? ground-truth points? were? located,? the? monitoring? results? of the two models were also similar by visual observation. In the two figures, the distribution trends of wheat powdery mildew were both relatively concentrated. In? comparison? with? the 32% of healthy? samples, 55% of mild? samples? and 13% of severe? samples for the? in-situ? investigation, they were 37%, 49% and 14% for the SLST-SVM model and 31%, 55% and 14% for? SMLST-SVM model, respectively. It can be seen that the SMLST-SVM model had a bet‐ter result than SLST-SVM model.

3.3 Analysis of influence factors

Temperature is one of the key factors to affectthe incidence of wheat powdery mildew, however, itis difficult and inaccurate to identify the disease insmall and medium-sized regions, due to constraintof low? spatial resolution of regular meteorologicaldata. Ma et al.[38] combined meteorological and re‐mote? sensing data to monitor wheat powdery mil‐dew, because the distribution of meteorological sta‐tions was too sparse. The primary objective of thisstudy is to? compare the relationship between LST and? the ?disease? severities? of wheat? powdery? mil‐ dew. It can be found that different LST data have significant impact on the accuracies of the disease diagnosis. For example, in the retrieval of LST from Landsat-8 data,? the? two-channel? nonlinear? splitter used in this paper was more reliable than the single- channel method[39]. The? spatial resolution of Land‐ sat-8 TIRS? data? and? the? temporal? resolution? of MOD11A1 data? can? both? meet? the? requirements. Therefore, the combination and fusion of both the images were performed to acquire a better perfor‐mance. The accumulated temperature and effective accumulated? temperature? are? key? factors? to? affect wheat? powdery? mildew[40]. Multitemporal? LST? is better to show the temperature influence on the dis‐ ease monitoring than a single one.

4 Conclusion

It is a progressive process for the occurrence of wheat powdery mildew, the cumulative effect must be considered with the disease development. To ac‐curately identify the disease, multisource and multi‐ temporal? GF-1,? Landsat-8 and? MOD11A1 were jointly utilized at a city? scale. The vegetation fea‐tures and LSTs are simultaneously adopted to mon‐itor the disease for improving the classification ac‐ curacy.

To find out the most sensitive vegetation fea‐tures to wheat powdery mildew, four most impor‐ tant growth stages were selected including the stand‐ing stage, jointing stage, flowering stage and milk‐ing? stage, which? are? also the? criteria? for? selecting satellite? images. Additionally,? it? has? a? progressive process for the disease incidence with the growth of wheat? and? changes? of meteorological? factors. As one of the most essential influencing factors, the ac‐ cumulative? effects? in? LSTs? must? be? considered when? identifying? the? disease. Landsat-8 TIRS hashigh spatial resolution but low temporal resolution,however, it is quite contrary to MOD11A1. As a re‐sult, the STARFM was selected to perform the spa‐tial-temporal fusion of both data. Four SVM modelswere? respectively? constructed? through? a? singleLandsat-8 LST (LST),? multitemporal? Landsat-8LSTs (SLST),? cumulative? MODIS? LST (MLST)and? the? combination? of cumulative? Landsat-8 andMODIS LST (SMLST).

The OA of LST-SVM model was improved by13% using the four temporal LSTs. In addition, theKappa coefficient also increased from 0.38 to 0.59,indicating that LST is a key habitat factor for the oc‐currence? and? development? of wheat powdery mil‐dew, due to a cumulative effect. On the other hand,the accuracies of MLST-SVM model were smallerthan that of SLST-SVM and SMLST-SVM models,indicating that it is inappropriate to apply MOD11A1data? directly? to? the? monitoring? of wheat powderymildew? in? a relatively? small? area. Conversely, theperformance of SMLST-SVM is slightly better thanthat? of SLST-SVM, indicating that the monitoringperformance can be enhanced by using a combina‐tion? and? fusion? of high-resolution? spatial-temporalremote sensing data.

References:

[1] ZHANG J, WANG N, YUAN L, et al. Discriminationof winter wheat disease and insect stresses using con‐tinuous wavelet features extracted from foliar spectralmeasurements[J]. Biosystems Engineering, 2017, 162:20-29.

[2] FENG W, SHEN W Y, HE L, et al. Improved remotesensing detection of wheat powdery mildew using dual-green? vegetation? indices[J]. Precision? Agriculture,2016, 17(5):608-627.

[3] GALLEGO F J, KUSSUL N, SKAKUN S, et al. Effi‐ciency assessment of using satellite data for crop areaestimation in Ukraine[J]. International Journal of Ap‐plied Earth Observation and Geoinformation, 2014, 29:22-30.

[4] SETHY P K, BARPANDA N K, RATH A K, et al. Im‐age processing techniques for diagnosing rice plant dis‐ease: A survey[J]. Procedia? Computer? Science, 2020, 167:516-530.

[5] YANG? C. Remote? sensing? and? precision? agriculturetechnologies? for? crop? disease? detection? and? manage‐ment with a practical application example[J]. Engineer‐ing, 2020, 6(5):528-532.

[6] ZHENG Q, YE H, HUANG W, et al. Integrating spec‐tral? information? and? meteorological? data? to? monitor wheat yellow rust at a regional scale: A case study[J]. Remote Sensing, 2021, 13(2): ID 278.

[7] HUANG W J, LAMB D W, NIU Z, et al. Identificationof yellow? rust? in? wheat using? in-situ? spectral? reflec‐tance measurements and airborne hyperspectral imag‐ing[J]. Precision Agriculture, 2007, 8(4-5):187-197.

[8] ZHANG? J? C, PU? R L, WANG? J H,? et? al. Detectingpowdery mildew of winter wheat using leaf level hy‐perspectral measurements[J]. Computers and Electron‐ics in Agriculture, 2012, 85:13-23.

[9] LUO J H, ZHAO C J, HUANG W J, et al. Discriminat‐ing? wheat? aphid? damage? degree? using 2-dimensional feature? space? derived? from? Landsat 5 TM [J]. Sensor Letters, 2012, 10(1-2):608-614.

[10] ZHENG Q, HUANG W, CUI X, et al. New spectral in‐dex? for? detecting? wheat? yellow? rust? using? sentinel-2 multispectral imagery[J]. Sensors, 2018, 18(3): ID 868.

[11] HE L, QI S, DUAN J, et al. Monitoring of Wheat pow ‐dery mildew disease? severity using multiangle hyper‐ spectral remote sensing[J]. IEEE Transactions on Geo‐ science and Remote Sensing, 2020, 59(2):979-990.

[12] ZHAO J, FANG Y, CHU G, et al. Identification of leaf-scale wheat powdery mildew (Blumeriagraminis f. sp. Tritici) combining hyperspectral imaging and an SVM classifier[J]. Plants, 2020, 9(8): ID 936.

[13] KHAN I H, LIU H, LI W, et al. Early detection of pow ‐dery mildew disease and accurate quantification of its severity? using? hyperspectral? images? in? wheat[J]. Re‐ mote Sensing, 2021, 13(18): ID 3612.

[14] ZHAO? J, XU? C, XU? J,? et? al. Forecasting? the wheatpowdery mildew (Blumeriagraminis f. Sp. tritici) us‐ing a remote sensing-based decision-tree classification at? a provincial? scale[J]. Australasian Plant Pathology, 2018, 47(1):53-61.

[15] LIANG W, CARBERRY P, WANG G, et al. Quantify‐ing the yield gap in wheat-maize cropping systems of the Hebei Plain, China[J]. Field Crops Research, 2011, 124(2):180-185.

[16] CHEN H, ZHANG H, LI Y. Review on research of me‐teorological conditions and prediction methods of crop disease and insect pest[J]. Chinese Journal of Agrome‐teorology, 2007, 28(2):212-216.

[17] YUAN L, PU R L, ZHANG J C, et al. Using high spa‐tial resolution? satellite imagery? for mapping powderymildew? at? a? regional? scale[J]. Precision? Agriculture,2016, 17(3):332-348.

[18] LOVELAND T R, IRONS J R. Landsat 8: The plans,the reality, and the legacy[J]. Remote Sensing of Envi‐ronment, 2016, 185:1-6.

[19] WANG W, LIANG S, MEYERS T. Validating MODISland? surface? temperature? products? using? long-termnighttime ground measurements[J]. Remote Sensing ofEnvironment, 2008, 112(3):623-635.

[20] HUANG L, JIANG J, HUANG W, et al. Wheat yellowrust monitoring based on Sentinel-2 Image and BPNNmodel[J]. Transactions of the Chinese Society of Agri‐cultural Engineering, 2019, 35(17):178-185.

[21] LIU R, ZAHNG S, JIA R. Application of feature selec‐tion? method? in? building? information? extracting? fromhigh? resolution? remote? sensing? image[J]. Bulletin? ofSurveying and Mapping, 2018, (2):126-130.

[22] BAO W, ZHAO J, HU G, et al. Identification of wheatleaf diseases and their severity based on elliptical-max‐imum margin criterion metric learning[J]. SustainableComputing: Informatics? and? Systems, 2021, 30: ID100526.

[23] QIN F, LIU D, SUN B, et al. Identification of alfalfaleaf? diseases? using? image? recognition? technology[J].PLoS One, 2016, 11(12): ID e0168274.

[24] ROBNIK- ?IKONJA M, KONONENKO I. Theoreticaland empirical analysis of ReliefF and RReliefF[J]. Ma‐chine Learning, 2003, 53(1):23-69.

[25] JORDAN C F. Derivation of leaf‐ area index from qual ‐ity of light on the forest floor[J]. Ecology, 1969, 50(4):663-666.

[26] ROUSE J W, HAAS R H, SCHELL J A, et al. Moni‐toring? vegetation? systems? in? the? great? plains? withERTS[C]// In Third ERTS Symposium Volume 1: Tech‐nical? Presentations. Washington,? DC,? USA: NASA,1973:309-317.

[27] GAMON J A, PENUELAS J, FIELD C B. A narrow-waveband spectral index that tracks diurnal changes inphotosynthetic efficiency[J]. Remote Sensing of Envi‐ronment, 1992, 41:35-44.

[28] HUETE A? R. A? soil-adjusted? vegetation? index (SA ‐VI)[J]. Remote Sensing of Environment, 1988, 25(3):295-309.

[29] LIU H, HUETE A. A feedback based modification ofthe NDVI to minimize canopy background and atmo‐spheric noise[J]. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience andRemote Sensing, 1995, 33(2):457-465.

[30] BROGE? N? H,? LEBLANC? E. Comparing? predictionpower? and? stability? of broadband? and? hyperspectralvegetation indices for estimation of green leaf area in‐dex and canopy chlorophyll density[J]. Remote? Sens‐ing of Environment, 2000, 76(2):156-172.

[31] RICHARDSON A J, WIEGAND C L. Distinguishingvegetation from soil background information[J]. Photo‐grammetric Engineering and Remote Sensing, 1977, 43(12):1541-1552.

[32] PENUELAS J, BARET F, FILELLA I. Semi-empiricalindices to? assess? carotenoids/chlorophyll? a ratio? from leaf spectral reflectance[J]. Photosynthetica, 1995, 31(2):221-230.

[33] DU C, REN H, QIN Q, et al. A practical split-windowalgorithm for estimating land surface temperature from Landsat 8? data[J]. Remote? Sensing, 2015, 7(1):647-665.

[34] REN H, DU C, LIU R, et al. Atmospheric water vaporretrieval? from? Landsat 8 thermal? infrared? images[J]. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres, 2015, 120(5):1723-1738.

[35] GAO? F,? MASEK? J,? SCHWALLER ?M,? et? al. On? theblending? of the? Landsat? and? MODIS? surface? reflec‐tance: Predicting? daily Landsat? surface reflectance[J]. IEEE? Transactions? on? Geoscience? and? Remote? Sens‐ing, 2006, 44(8):2207-2218.

[36] OLATOMIWA L, MEKHILEF? S,? SHAMSHIRBANDS,? et? al. A? support? vector? machine-firefly? algorithm-based? model? for? global? solar? radiation? prediction[J].Solar Energy, 2015, 115:632-644.

[37] HUANG L, LIU W, HUANG W, et al. Remote sensingmonitoring of winter wheat powdery mildew based onwavelet analysis and support vector machine[J]. Trans‐actions? of the? Chinese? Society? of Agricultural? Engi‐neering, 2017, 33(14):188-195.

[38] MA H, HUANG W, JING Y. Wheat powdery mildewforecasting? in? filling? stage? based? on? remote? sensingand? meteorological? data[J]. Transactions? of the? Chi‐nese Society of Agricultural Engineering, 2016, 32(9):165-172.

[39] XU? H. Retrieval? of the? reflectance? and? land? surfacetemperature? of? the? newly-launched? Landsat 8 satel‐lite[J]. Chinese? Journal? of? Geophysics-Chinese? Edi‐tion, 2015, 58(3):741-747.

[40] SHARMA A K, SHARMA R K, BABU K S, et al. Ef‐fect of planting options and irrigation schedules on de‐velopment of powdery mildew? and yield of wheat inthe North Western plains of India[J]. Crop Protection,2004, 23(3):249-253.