Life, Entangled

The glass case is lined by dozens of palm-sized miniature beds—but not the warm, supportive kind that invites a good nights sleep. Rather, twisted together from charred copper coils the artist found in electronic repair shops in the 1990s, these bed frames look rugged and even feverish. Each is entangled with a wild web of silk and, occasionally, a cocoon that serves as both the occupants cradle and coffin.

Each bed, a vestige of the life and work of a silkworm, conjures up an image of its beginning: a naked worm squirming on naked wires, a creature very out of place, trying to make sense of the surroundings life has given it.

“Beds/Nature Series No.10” is just one thread that makes up “A Silky Entanglement,” a solo exhibition from interdisciplinary artist Liang Shaoji, curated by Hou Hanru, currently on view at the Power Station of Art in Shanghai. Liangs work spans a variety of media and formats with one main theme: the life processes of silkworms, whom he calls his “collaborative partners.”

These partners have guided him to create “Beds/Nature Series No.10.” In the Shanghai-born artists work with silkworms in the early 1990s, he guarded them day and night. One night, Liang woke up on the floor to find a silkworm had fallen on him and spun a thin cocoon on his collar. He had an epiphany, “Consumed by the pursuits of life, am I not a silkworm myself?”

Combining this experience with the Daoist idea ofqi wu(齊物), transcending above the differences of this world to find equality among all things, Liang arrived at the idea of “Beds”: We begin and end our lives on beds, while spending most of our living hours on them too. By subjugating silkworms, quite literally, to the same process of exhausting an entire life on a bed, Liang harvests a visual impression of a chaotic liveliness and distilled all that is beautiful and futile about existence.

Silk became one of Chinas chief exports in the Han dynasty (206 BCE – 220 CE) and has been an internationally valued commodity since. However, Liangs experiments with having silkworms produce silk on various surfaces and structures is a far cry from the materials usual symbolism of luxury and oriental mystique in the West.

In Chinese culture, silk has spawned a plethora of metaphors, sometimes contradictory, about attitudes toward life. In an interview with news site The Paper about the current exhibition, Liang muses that on one hand, there is the Chinese saying, “The spring silkworm does not stop spewing silk until it dies (春蠶到死絲方盡),” in praise of silkworms spirit of devotion. On the other, there is “spin a cocoon around oneself (作繭自縛),” which mocks someone who is trapped in the consequences of their own doings. Liang relishes the creative tension born out of these paradoxes, which make silk intriguing as an artistic medium.

As some exhibited works are highly conceptual, and their descriptions are laden with cultural references to Daoism, Buddhism, and Western schools of thought, “A Silky Entanglement” sometimes risks being esoteric to audiences new to Liangs works.

However, works in the exhibition showcase Liangs continuous exploration with metaphors and metamorphoses. The poignant piece “Wenchuan Stones” consists of rocks and bricks Liang harvested from Wenchuan, Sichuan province, after the devastating earthquake of 2008. Now sitting on the gallery floor, the roughened surfaces of these objects, painful remnants of a traumatic event, are smoothed out by thin layers of silk. Together they form something both heavy and light, dead and alive—the stones and the silk stand in contrast, yet are bound in a tight unity of trauma and healing.

Liang uses contrasts not just to complement, but to confront. One room over from “Wenchuan Stones” is “Cloud Kiln,” where silkworms have spewed silk over fragments of ancient porcelain and a structure modeled after an ancient kiln. Porcelain and silk, two prominent cultural symbols of China, expose each others vulnerabilities: one to cut open with its sharp edges, the other to cover up and protect; while the broken kiln and porcelains remind of decline and decomposition, the silk signifies regeneration. This is a site on which forces tug each other over time into a delicate balance—a seeming stasis that is in fact the result of continuous evolution.

Liang does not want to only remain a witness or conductor of these metamorphoses. He wants to be part of it. He takes a closer look at the analogy between humans and silkworms in his creative notes on view at the exhibition: “I further fancied that, wouldnt the breath of everything on the earth be deemed as some kind of gasification of spinning? Arent the imprints on earths surface left by various human activities also some kind of deformed variation of silk traces?... In this regard, the earth has already been a thick cocoon covered with silk traces for ten thousand years.”

Viewers might look sideways at this constant emphasis by Liang of equality between human and worm. After all, on the labels next to each piece, while Liangs name stands in the spot reserved for the artist, “silk” or “cocoon” among the list of media are the only credit his artisans get. Cooped up in their beds or forced to wander across metal or stone, the silkworms merely follow the path laid out by Liang, their creative freedom limited to the parameters he sets them.

A few rooms down from “Beds,” however, viewers might find a sincere reflection on this dynamic. “Studio,” a replica of Liangs Mount Tiantai studio in which he worked with, studied, and raised silkworms, is almost like another version of “Beds”—only it duplicates the setting where Liang had the epiphany that kindled “Beds” down to the shirt he was wearing, with a cocoon on his collar, displayed on the floor. Just as silkworms have enlivened “Beds” and other works with the traces of their lives, Liang subjects his own lifes traces to viewers gaze in “Studio.”

This room, perhaps along with this whole exhibition, is Liangs very own entangled web of silk and cocoon. – Siyi Chu (褚司怡)

“Time and Permanence,” inkjet print, 2013

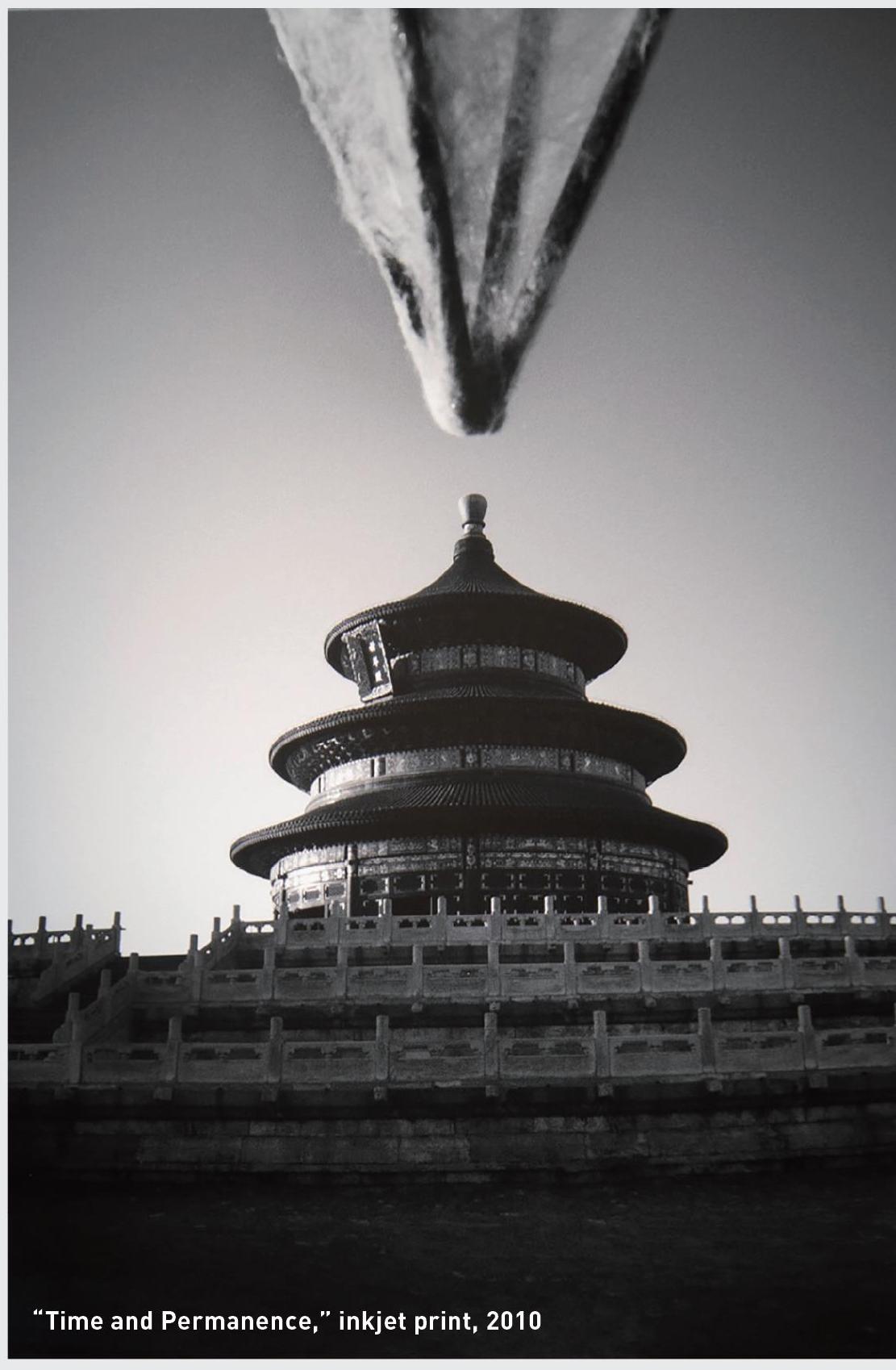

“Time and Permanence,” inkjet print, 2010

“Beds/Nature Series No. 10,” charred copper, silk, cocoon, 1993-2021

Images Courtesy of Liang Shaoji and Power Station of Art

In the Artists Words

The international art world was confused when they tuned in to Liang Shaoji around the turn of the current century. “I went abroad and people there told me, ‘You have interesting ideas, but your work is impossible to categorize. Is it fiber art? Sculpture? What is it?” Liang shared during the press conference for “A Silky Entanglement,” his latest exhibition in Shanghai.

The skepticism did not discourage him, but rather inspired him to push boundaries in his creative journeys with silkworms. Guided by curiosity, he draws artistic inspiration and meditative insights from the worm, whom he has likened to “a friend and mentor” in the exhibitions press release, and termed during the press conference “a portal through which [he] examines life, society, and the cosmos.” In a phone call with TWOC, Liang talks about the experience of working with silkworms and becoming an internationally acclaimed artist.

How do you collaborate with silkworms?

Its been 32 years since I first started raising silkworms. The idea started brewing in 1988. I was working on a piece called “Yi Series—Magic Cube,” for which I built cubic structures with wooden frames and silk. On the silk, I fixed some dried silk worm cocoons. The parts in “Magic Cube” were movable. The cocoons projected layers of shadows through this movement, looking as if they were alive. Thats when I thought, why dont I actually use live silkworms for an experiment?

In 1989, I took some metal frames to the Zhejiang University of Agriculture, and proposed to raise silkworms on them. The professor there thought it was nearly impossible because silkworms and metal are not compatible. Indeed, the silkworms all escaped after flopping around on the metal. But eventually I discovered that, even though the worms didnt want to stay, they still left small traces of silk on the surface, so gradually, silkworms that came later were willing to stay on the spot longer and longer as more silk accumulated.

My first phase from the end of the 1980s to the 1990s was spent in getting to know the silkworms: I studied their pathology and biological clocks, their preferences in different phases of life, physiological changes, and behaviors. Now I continue to collaborate with scientists to study silkworm genetics, or turn their existing findings into artistic expression. For example, we injected fluorescent proteins from marine life into the silkworms to have them spit out fluorescent silk.

During the press conference, you mentioned that cultures should be in symbiosis, in conversations. What role do you see yourself playing in this?

I visited Germany and France in 1982 and 1983, and then the US. When I returned, I felt strongly that Chinese culture and arts could not just stay where it was. I felt that Chinas traditional culture was inexhaustible for artists, but we desperately needed new perspectives. That was when I started experimenting more.

There are a lot of questions already on scientists radar. As an artist, I have bigger space to experiment, so I dont think I am bound by being Chinese or international. In 2009, the Prince Claus Awards [an honor for cultural development partially funded by the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs] marked me as a “conceptual artist,” but I feel that my “Nature” series cannot be summed up by such a label. With great curiosity, I meditate and explore, ask questions with reverence, and use my own findings to decode the boundless universe. – S.C.

Born in 1945 in Shanghai, Liang Shaoji currently lives and works in Tiantai, Zhejiang province. He studied soft sculpture from Maryn Varbanov, one of the world's leading fiber artists, at the China Academy of Art. For more than 30 years, Liang has indulged in interdisciplinary creations of art and biology, installation and sculpture, and new media and textile. His “Nature” series sees the life process of silkworms as its creative medium, the interaction in natural world as its artistic language, and time and life as its essential idea. His works are filled with a sense of philosophy and poetry while illustrating the inherent beauty of silk.

“Heavy Clouds” (detail), ancient camphor wood, silk, cocoons, 2014-2021

“Fluorescence,” fluorescent cocoons, LED, acrylic box, 2021

“The Temple” (PSA edition), silk, barbed wires, cocoons, acrylic sheet, resin corrugated sheet, steel-frame structure, 2013-2021

Images Courtesy of Liang Shaoji and Power Station of Art, Portrait Photography by Lin Bingliang and Provided by ShanghART Gallery