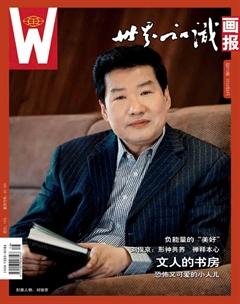

形神共養 禪釋本心

劉曦林

Practicality and aesthetic value were the two principles Chinese calligraphy followed in its evolvement. The beauty in Chinese calligraphy can nurture and comfort a soul with its lines, structures, and rhythms.

However in modern days, fewer and fewer people would touch a pen in their daily lives, not to mention practice calligraphy. Boiling material needs also burned modern peoples souls. Would it be possible to find a peaceful place for a tired heart? Liu Junjing, as a traditional Chinese medicine doctor and calligrapher, gave his prescription: practicing regimen calligraphy. In fact, regimen calligraphy was regarded as an effective way to keep health since ancient times, and the theory was also verified by modern medical research. Liu Junjing tried to pick up again the practicality side of Chinese calligraphy and popularize it to the public with his humanistic care to the modern souls; therefore lead the public to a path of harmonious life.

實用和審美,是人類文明得以持續發展的雙翼,也是中國書法演化發展所依循的兩條主線。實用先于審美,審美升華了實用。

具有獨特文化基因的中國書法,以淵雅的氣息化育著中華文明從古代走向現代,由此形成歷久常新的人文傳統。

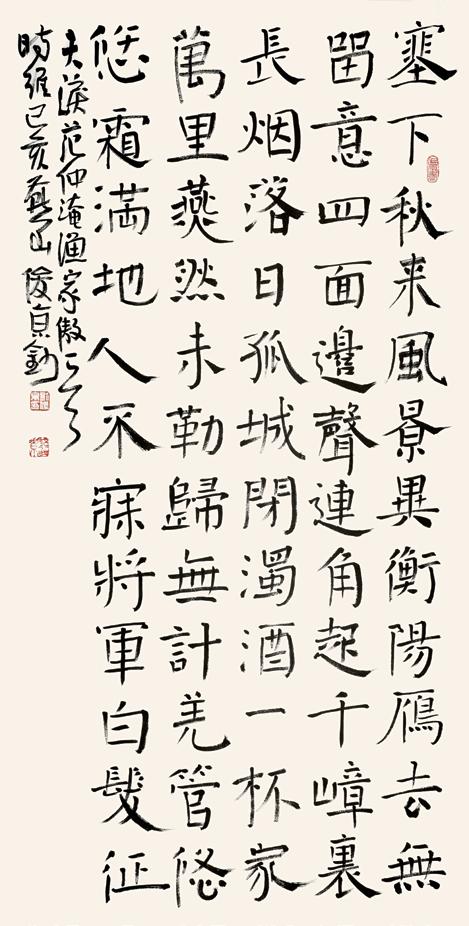

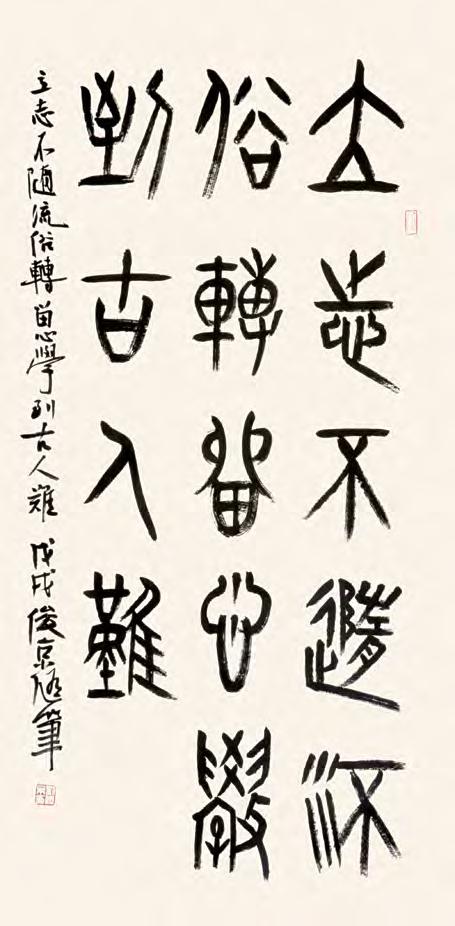

上個世紀,林語堂先生曾以“書法是中國美學的基礎”著文,將中國書法之美歸納為萬物有靈的原則。他從“一切藝術問題都是韻律問題”出發,分析對比中、西方藝術:西方藝術,多耽于聲色,以滿足人的感官刺激;中國藝術精神,則較為高雅、含蓄,和諧于自然。中國人對韻律理想的崇拜首先是在書法藝術中發展起來的。漢字書法可表現富于情感的線條節奏之美,這是和其他民族文字不同的地方。西方人對中國書法的關注點主要在于“一條線表達內在感情”,而對書法行為在自我實現與自我超越的價值問題上,在現代藝術出現之前幾乎一無所知。

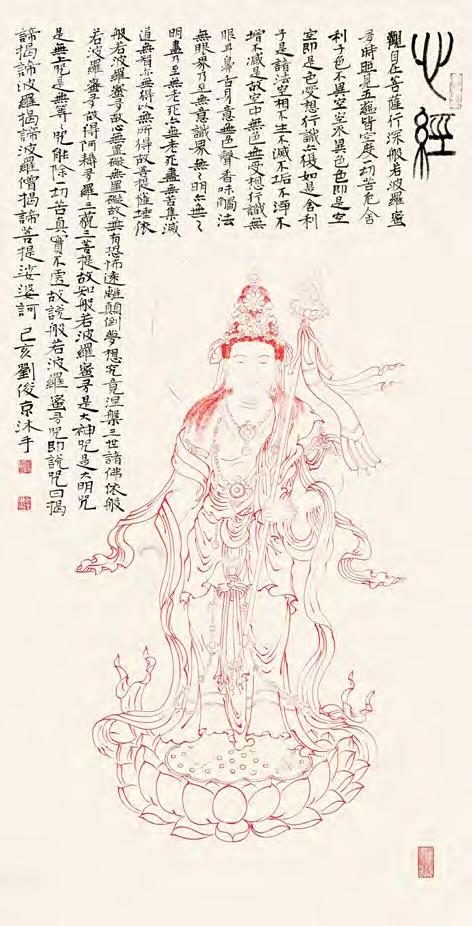

中國書法在意態上的高度抽象與表現上的極為簡約、凝練,造就了一片自由無垠的天地,中國人通過書法訓練了自己對各種美質的欣賞力與創造力。字形線條的優雅、精微、婉轉、迅捷、剛勁、雄渾、激越、粗獷、古拙等各種美感,是書法家對世間物像、情態的感悟,通過書法轉化為人格化的審美意象。“作一字須數種意,故先貴存想,馳思造化之故,寓情深郁豪放之間,象物于飛潛動植流峙之奇,以疾澀通八法之則。”一個寫得好的字,無論繁簡、書體,都可以在字形結構中保持非常和諧,蘊藉美感平衡。……

- 世界知識畫報·藝術視界的其它文章

- 劉長鑫作品欣賞

- 郭德福作品欣賞

- 黃瑋作品欣賞

- 郭英華作品欣賞

- Supreme,從街頭到殿堂

- 變革的時代,變革的中國畫