抗癌肽的作用機制研究進展

喬雪,王義鵬,于海寧

抗癌肽的作用機制研究進展

喬雪1,王義鵬2,于海寧1

1 大連理工大學 生物工程學院,遼寧 大連 116024 2 蘇州大學 生命科學學院,江蘇 蘇州 215123

近年來癌癥的發(fā)生率和死亡率呈現(xiàn)逐漸上升的趨勢,是威脅人類生命的主要疾病之一。抗癌肽 (Anticancer peptides,ACPs) 即具有抗腫瘤活性的生物活性肽,其廣泛存在于多種生物體內,包括哺乳動物、兩棲類動物、昆蟲、植物和微生物等。抗癌肽在治療腫瘤方面具有眾多優(yōu)勢,如分子量低、結構簡單、高抗癌活性、高選擇性、較少的副作用、多種給藥方式、不易引起多重耐藥性等。文中結合本課題組相關工作,歸納了目前所發(fā)現(xiàn)的抗癌肽的作用機制,以期為新型肽類抗腫瘤藥物的研發(fā)提供一定的方向。

抗癌肽,膜裂解機制,非膜裂解機制,新型抗腫瘤藥物

癌癥也稱為惡性腫瘤,是一種由調控細胞分裂增殖機制失常而引起的疾病。據(jù)國際癌癥研究機構估計,在全世界范圍內,2018年新增癌癥患者約為1 810萬,死亡人數(shù)約960萬[1]。據(jù)估計在2025年全球每年的新增癌癥病例將超過2 000萬[2]。目前,手術治療、放射治療(放療) 和化學藥物治療(化療) 是主要的傳統(tǒng)癌癥治療方法。然而傳統(tǒng)的抗癌類藥物雖然抗癌效率較高,但是也存在一些缺點,如低選擇性、副作用明顯、免疫抑制、神經(jīng)和腸胃損傷等[3-4];更重要的是,這些抗癌類藥物的聯(lián)合使用極易引起腫瘤的多藥耐藥性(MDR)[5]。因此,腫瘤的藥物治療期待著新的突破。抗菌肽(AMPs) 是一類天然產(chǎn)生的先天免疫的重要防御物質,抗菌肽功能多樣,其中將具有抗腫瘤活性的抗菌肽叫做抗癌肽(ACPs)。而抗癌肽的特殊作用機制,使其成為近年來生物藥物研究中的一個熱點,也為新型抗癌藥物的研究提供了新方向。

1 抗癌肽的基本特征

目前發(fā)現(xiàn)的抗癌肽可分為兩類:一類是對細菌和癌細胞有殺傷作用,但是對正常細胞沒有毒性,如cecropins和magainins。另一類是對細菌、癌細胞和正常細胞均有破壞作用,如昆蟲defensins和tachyplesin Ⅱ等[6]。因此第一類抗癌肽具有很好的研究價值和應用前景。抗癌肽的長度和序列多樣,但大部分抗癌肽都有兩個共同特征:陽離子性和兩親性。抗癌肽通常由5–40個氨基酸組成,其中精氨酸、賴氨酸和組氨酸的存在使其表現(xiàn)出較強的陽離子特性,表面凈電荷范圍為+2–+9[7-8]。抗癌肽既具有親水性又具有親脂性,主要是因為其結構上具有親水性和疏水性的側鏈結構,而絕大多數(shù)的抗癌肽含有α-螺旋或β-折疊結構,這種兩親性側鏈在具有α-螺旋結構的抗癌肽鏈上分別排布在螺旋的兩側,或者集中于兩端,因此可形成親水面和疏水面或者明顯的親水端和疏水端[9]。當抗癌肽與癌細胞膜相互作用時,疏水區(qū)域與胞膜脂質結合,帶正電荷的親水區(qū)域與帶有負電荷的癌細胞膜表面通過靜電吸附而有效結合,這為抗癌肽能夠選擇性作用于癌細胞奠定了基礎[10]。

2 抗癌肽的作用機制

2.1 抗癌肽的膜裂解機制

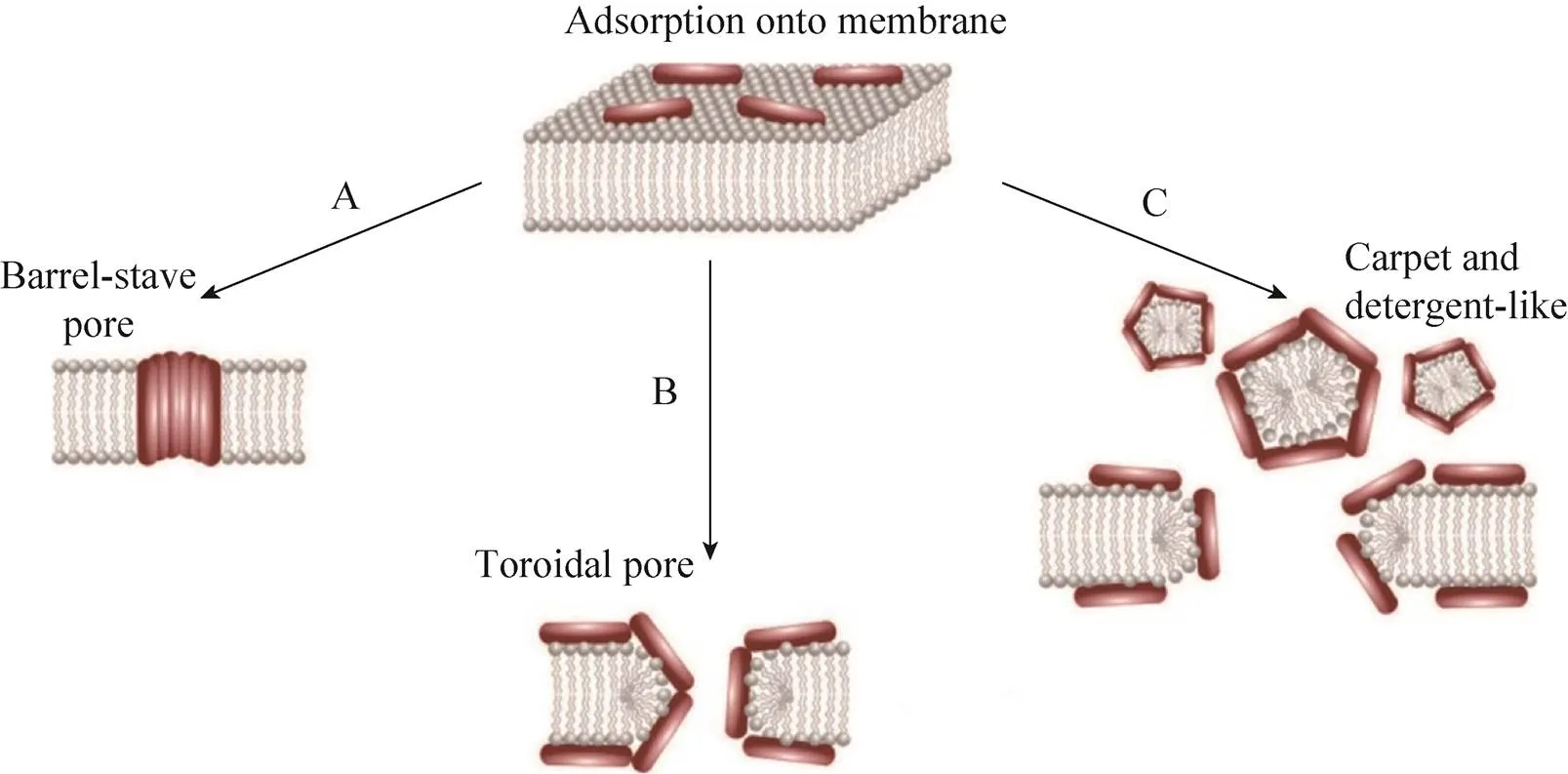

抗癌肽能夠靶向作用于癌細胞,而不損傷正常組織細胞的主要原因在于癌細胞膜表面一些陰離子成分的特異性表達,包括磷脂酰絲氨酸、-糖基化粘蛋白、唾液酸神經(jīng)節(jié)苷脂和肝素等[11]。大量研究表明,抗癌肽的作用機制可以分為膜裂解機制和非膜裂解機制(圖1和圖2)。其中抗癌肽的膜裂解機制主要有以下3種,分別是“桶板模型”、“氈毯模型”和“環(huán)形孔模型”(圖1)[12-13]。

圖1 抗癌肽的膜裂解機制[13]

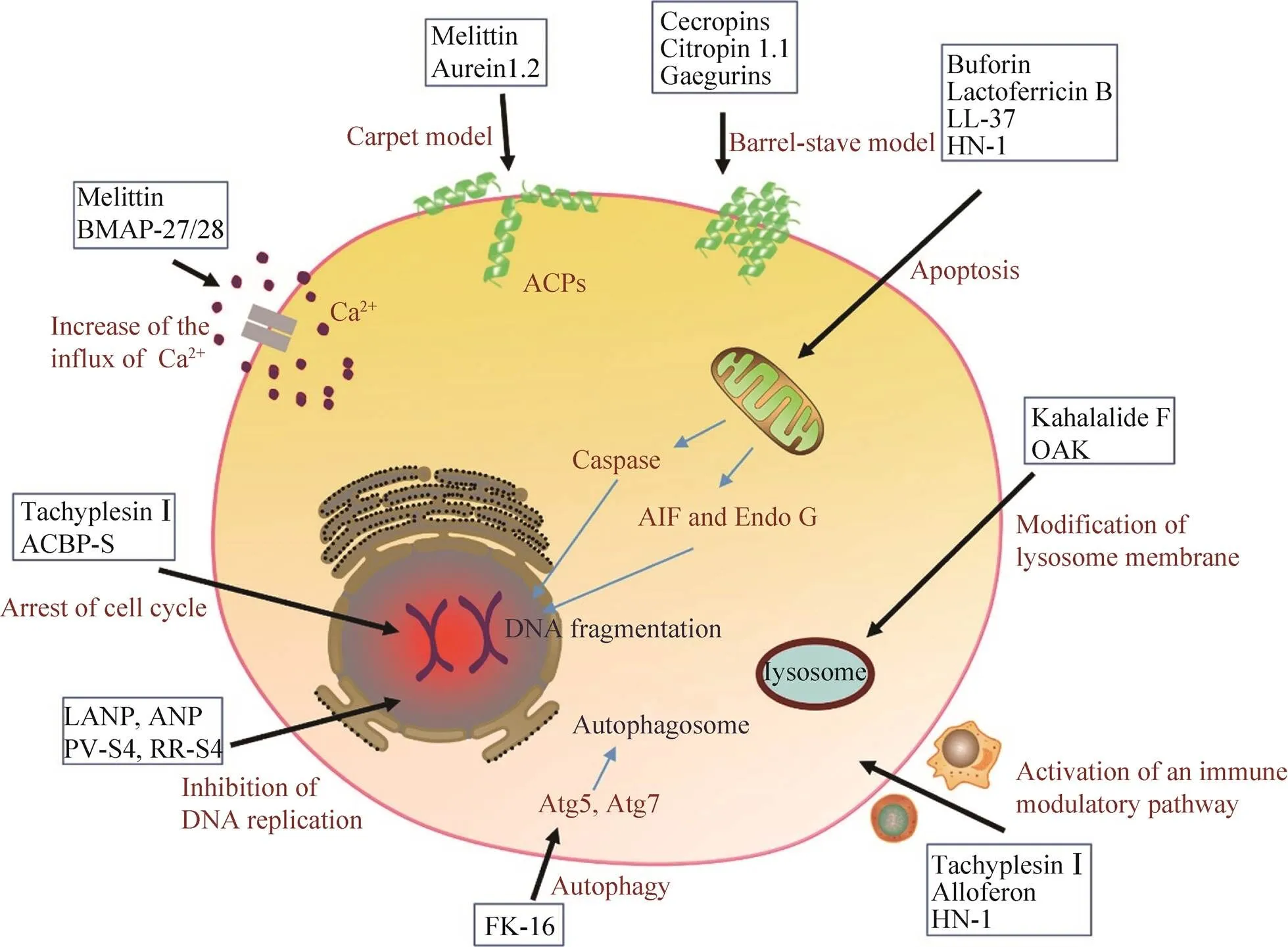

圖2 抗癌肽的抗腫瘤機制

2.1.1 桶板模型

1977年Ehrenstein等首次提出了抗菌肽的桶板模型(圖1)[14]。抗癌肽在癌細胞膜表面通過疏水作用寡聚體化,其中抗癌肽的疏水面向外朝向細胞膜的酰基鏈,而親水面形成孔或槽,最終在不斷的聚集過程中形成穿透質膜離子孔道,進而導致癌細胞內容物流出,失去大量離子和能量,胞內滲透壓改變,進而瓦解細胞膜。理論上這種孔道至少由3個抗癌肽分子組成,并且要求它們有一定的二級結構,比如兩親性的α-螺旋、β-折疊或同時含有α-螺旋和β-折疊[15]。很多抗癌肽均被證明是通過桶板模型來發(fā)揮其抗癌作用的。如在1994年,Sui等證明了分離自意蜂的Melittin可以通過桶板模型破壞癌細胞膜的完整性[16]。Melittin又名蜂毒肽,是蜂毒的主要成分,由26個氨基酸殘基組成,其功能多樣,如有抗炎、鎮(zhèn)痛、抗菌、抗HIV及抗腫瘤等多種藥理活性[17]。蜂毒肽具有廣譜的抗腫瘤活性,包括人肝細胞癌、白血病、乳腺癌等,桶板模型是其多種抗腫瘤機制之一[18-19]。來自咆哮草蛙的抗癌肽Aurein1.2對白血病、肺癌、結腸癌等均有殺傷作用,其主要機制也是通過桶板模型來破壞腫瘤細胞[20]。

2.1.2 氈毯模型

1992年Pouny等提出了抗菌肽的“氈毯”模型[21]。陽離子抗癌肽也可以通過靜電作用結合到帶負離子的癌細胞膜上,以類似氈毯的結構平行排列,當抗癌肽達到臨界濃度時,細胞膜能量惡化,穩(wěn)定性降低而出現(xiàn)顯著的彎曲從而破裂(圖1)。區(qū)別于桶板模型,氈毯模型不需要抗癌肽具有特殊結構,并且不形成跨膜通道[15]。Cecropins類抗癌肽,又名天蠶素,是第一個被發(fā)現(xiàn)的動物抗菌肽,在昆蟲和哺乳類動物中均有發(fā)現(xiàn),其對白血病、膀胱癌等均有強殺傷作用,可通過氈毯模型發(fā)揮作用[22]。Chuang等報道了人體唯一一種Cathelicidin類抗菌肽LL-37,也可以通過氈毯模型選擇性地裂解卵巢癌[23]。另外,Magainins (來自非洲爪蟾,)[24]、Citropin 1.1 (來自雨濱蛙,)[25]、Gaegurins (來自皺皮蛙,)[26]等多種抗癌肽,均可通過氈毯模型來發(fā)揮其抗癌作用。

2.1.3 環(huán)形孔模型

在環(huán)形孔模型中,抗癌肽的疏水區(qū)與癌細胞膜上的疏水區(qū)相互移動而導致胞膜破裂缺失,最終形成跨膜孔道(圖1)。其與桶板模型最主要的區(qū)別在于抗癌肽始終與磷脂的頭部結合而一起構成跨膜通道。1997年,Matsuzaki等報道了Magainin-2可以“環(huán)形孔”模型發(fā)揮抗菌作用[27]。Magainins,又名爪蟾素,分離自非洲爪蟾的皮膚,是較早發(fā)現(xiàn)的兩棲動物抗菌肽,其具有廣譜的抗菌抗癌活性,其中可以通過環(huán)形孔模型破壞人的宮頸癌細胞HeLa的細胞膜[28]。

除了上述3種機制外,還有一種破膜機制叫做Shai-Huang-Matsuzaki (SHM) 模型,被認為是氈毯模型和環(huán)形孔模型的結合[29]。這些模型雖然都是抗癌肽與癌細胞膜的相互作用導致細胞膜裂解,但是其內在的分子機制有所不同。但是,大量報道證明,許多抗癌肽可以通過不同的作用方式應對不同的癌細胞,以Magainin類抗癌肽為例,其抗癌作用方式既有環(huán)形孔又有氈毯模型,甚至還有非膜裂解機制[24,28,30]。

2.2 抗癌肽的非膜裂解機制

抗癌肽的作用機制除了改變癌細胞膜通透性以外,還可以與癌細胞的內源靶標相互作用,進而誘導癌細胞的死亡(圖2)。

2.2.1 誘導凋亡途徑

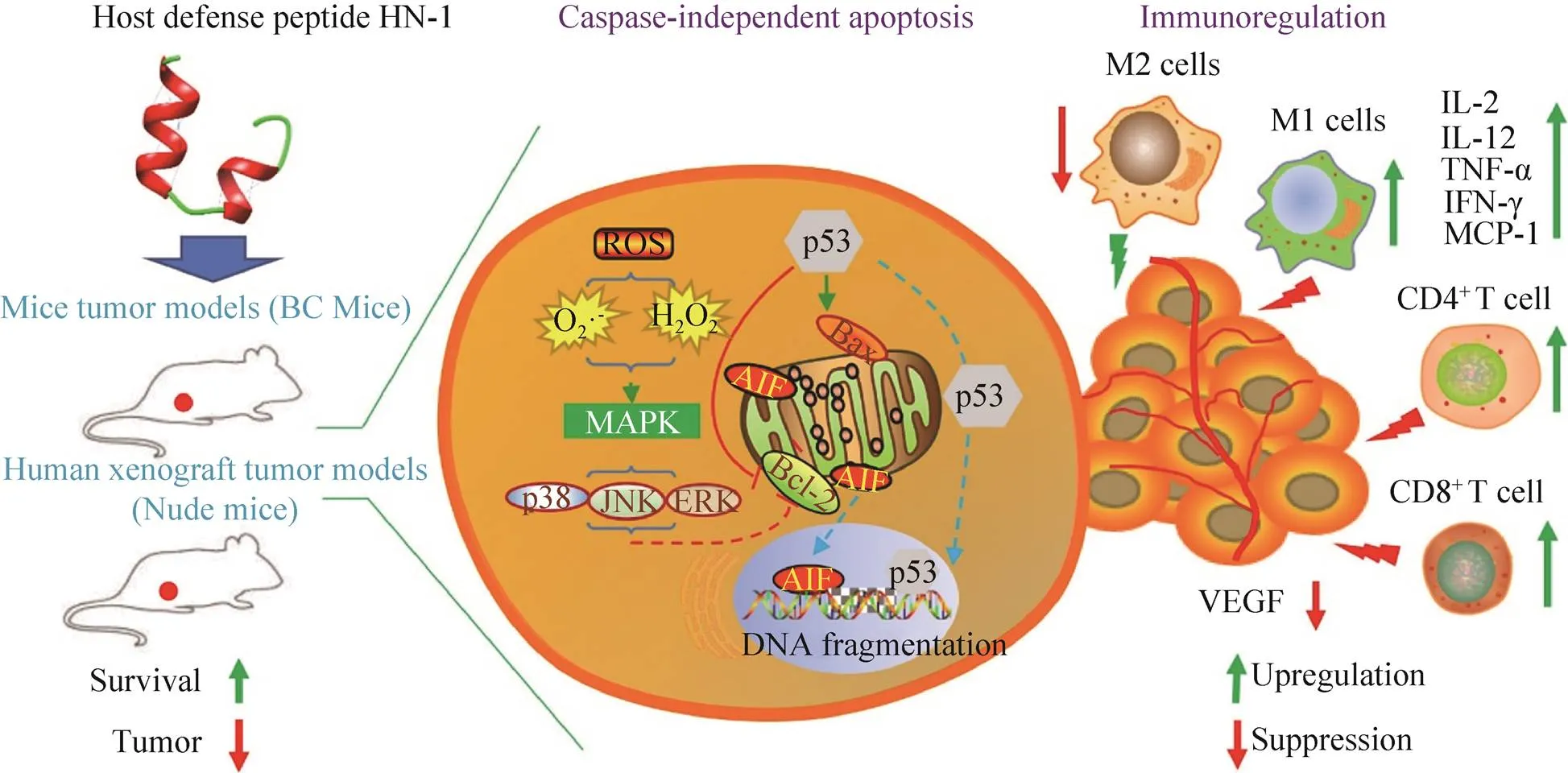

大量的研究證實抗癌肽可通過激活凋亡通路來執(zhí)行功能,凋亡細胞表現(xiàn)出一系列形態(tài)和生化特征的變化,如胞質皺縮、磷脂酰絲氨酸外翻、染色質凝聚、DNA片段化、核膜核仁破碎等[31]。一般來說凋亡分為內源性凋亡即線粒體途徑和外源性凋亡即死亡受體途徑,其中半胱天冬酶(Caspase)-9和-8分別是二者標志性中間激活物,caspase-3,6,7是二者共同的凋亡執(zhí)行者[32]。Lee等發(fā)現(xiàn)來自中華大蟾蜍的抗癌肽BuforinⅡb對多達62株癌細胞都有強殺傷作用,其可破壞線粒體膜,釋放細胞色素,進而激活caspase級聯(lián),誘導一系列蛋白水解反應導致細胞瓦解(內源性凋亡)[33]。Chen等將tachyplesinⅠ的C端連接一段帶有RGD的短肽,發(fā)現(xiàn)獲得的RGD-tachyplesinⅠ在體內外均可抑制腫瘤生長,并且激活caspase-3,6,7,8,9以及fas配體相關死亡域表達,也就是說其可同時激活線粒體途徑和死亡受體途徑[34]。不僅如此,近年來相繼出現(xiàn)很多報道證明抗癌肽還能夠激活不依賴于caspase的凋亡通路。這種凋亡通路不需要caspase的激活,而是促使存在于線粒體內外膜間隙的細胞凋亡誘導因子(AIF) 和核酸內切酶G (EndoG) 核轉移,進而引起DNA裂解和染色質凝集等[35]。Ren等發(fā)現(xiàn)LL-37是通過激活caspase非依賴性的凋亡通路抑制人結腸癌細胞的生長。LL-37有效激活細胞中的抑癌基因p53的表達,進而誘導多種轉錄靶標的表達包括Bcl-2家族的促凋亡蛋白如BAX、Bak和Puma,這些因子能促進線粒體生理機能的改變,進而釋放AIF和EndoG進入細胞核執(zhí)行凋亡功能[36]。本實驗室前期工作從海南湍蛙中提取到了一種抗菌肽HN-1具有廣譜的抗菌活性[37],后續(xù)實驗發(fā)現(xiàn)其對癌細胞具有選擇性殺傷作用,且有效激活了caspase非依賴性的凋亡通路抑制人乳腺癌細胞MCF-7的生長(圖3)。

2.2.2 阻止細胞周期于G0、G1或S期

細胞周期是細胞生命活動的基本過程,其依賴于各級調控因子的精確調控。大量報道指出抗癌肽可阻滯癌細胞于不同時期,從而抑制癌細胞的增殖。Li等[38]發(fā)現(xiàn)TachyplesinⅠ使人肝癌細胞SMMC-7721細胞阻滯在G0/G1期,實驗中TachyplesinⅠ下調突變p53、細胞周期蛋白D1和CDK4的蛋白水平,降低c-Myc的mRNA 水平,并且促進p16 和p21WAF1/CIP1的表達,可見TachyplesinⅠ通過對這些細胞周期相關基因表達的調節(jié),進而抑制SMMC-7721的增殖。Zhao等利用原核表達獲得抗癌肽AGAP的重組體rAGAP,發(fā)現(xiàn)rAGAP能夠抑制人膠質瘤細胞SHG-44的增殖和遷移,其機理是通過抑制G1細胞周期調控蛋白CDK2、CDK6和p-RB的表達,使SHG-44細胞周期被阻滯在G1階段,進而顯著抑制其增殖[39]。將胡桃肽WP1與納米硒結合能夠阻滯MCF-7細胞于S期,進而抑制其增殖[40]。

2.2.3 破壞溶酶體

癌細胞中溶酶體的通透性通常會發(fā)生改變,并且合成分泌大量的組織蛋白酶,它們與腫瘤的生長、侵襲和轉移息息相關[41]。據(jù)報道一些抗癌肽可以破壞溶酶體膜,釋放溶酶體內容物,導致細胞內環(huán)境酸化,直至癌細胞死亡[42]。如來自一種海參的抗癌肽Kahalalide F (KF),可以通過破壞癌細胞溶酶體結構來殺死癌細胞,其抑制的細胞株包括結腸癌、乳腺癌、非小細胞肺癌、前列腺癌、黑色素瘤等[43]。宿主防御肽模擬物OAK對小鼠前列腺腺癌細胞TRAMP-C2及其動物模型均有良好的抑制作用,并且可以克服多藥耐藥性。Held-Kuznetsov等發(fā)現(xiàn),OAK的作用機制是通過破壞線粒體和溶酶體發(fā)揮作用[44]。

2.2.4 增加鈣離子內流

癌細胞中Ca2+穩(wěn)態(tài)會發(fā)生改變,這些改變與腫瘤的發(fā)生、增殖、代謝和血管的生成有關[45]。抗癌肽可改變細胞膜通透性而進入細胞,并且可增加細胞內Ca2+內流,隨后通過靜電吸附作用于線粒體,在Ca2+的協(xié)同下作用于線粒體通透性轉換孔 (PTP),導致內容物外流引起癌細胞死亡。蜂毒肽Melittin可以通過增強Ca2+的流入和桶板模型等機制來殺死人的肝癌細胞[46]。另外,Risso等也發(fā)現(xiàn)來自家牛的BMAP-27/28對白血病、淋巴癌等都有很好的抑制作用,其機制就是改變細胞膜的通透性和提高細胞中Ca2+內流,并伴隨著DNA的片段化,進而誘導癌細胞的死亡[47]。

2.2.5 抑制DNA合成

誘導靶細胞DNA片段化是多種抗癌肽的作用效果,但不一定是抗癌肽直接作用于DNA,比如凋亡通路也會引起DNA斷裂。近年來研究發(fā)現(xiàn)有些抗癌肽可以直接與癌細胞染色體DNA或相關酶相互作用,進而干擾或抑制癌細胞的DNA合成。Gower等[48]發(fā)現(xiàn)4種利尿鈉肽(LANP、ANP、BNP和CNP) 對人的結腸癌細胞有抑制作用,其抗腫瘤機制就是通過抑制環(huán)磷酸鳥苷(Cyclic GMP) 介導的癌細胞DNA合成來阻止癌細胞增殖的。Hariton-Gazal等[49]通過實驗發(fā)現(xiàn)經(jīng)過加工改造后的抗癌肽PV-S4和RR-S4可以結合到Hela細胞核染色體上,使其DNA出現(xiàn)斷裂,進而誘導腫瘤細胞死亡。另外,分離自的抗癌肽Kahalalide F (KF)、來自淀粉核小球藻的CPAP等均能通過阻止DNA復制來殺死腫瘤細胞[18]。

2.2.6 促使癌細胞自噬

細胞自噬也稱Ⅱ型程序性細胞死亡,是細胞中高度保守的自行降解過程,自噬使饑餓或缺乏生長因子的細胞得以暫時成活,而那些持續(xù)不能獲得營養(yǎng)的細胞將消化所有可獲得的基質,最終導致自噬相關性細胞死亡。近年來發(fā)現(xiàn)其也是抗癌肽的腫瘤抑制機制之一[50-51]。Ren等[52]報道了LL-37的片段FK-16 (第17–32個氨基酸) 可誘導結腸癌細胞HCT116凋亡和自噬,但是對正常結腸上皮細胞NCM460毒性很小。FK-16提高了結腸癌細胞中自噬相關蛋白LC3-Ⅰ/Ⅱ、Atg5和Atg7的表達量,同時在共聚焦和電子顯微鏡下觀察到LC3陽性的自噬體的形成。當敲除掉Atg5和Atg7后,大大降低了FK-16對結腸癌細胞的殺傷作用,說明誘導癌細胞自噬是FK-16發(fā)揮作用的重要機制。

2.2.7 激活腫瘤免疫

免疫系統(tǒng)在機體控制和清除腫瘤方面起到了至關重要的作用,但仍難以阻止腫瘤的發(fā)生和發(fā)展。這與復雜的腫瘤微環(huán)境密不可分,一方面,腫瘤細胞可分泌促進腫瘤生長、轉移的細胞因子,如轉化生長因子-β、血管內皮生長等[53];另一方面,惡性腫瘤可以通過多重機制免疫應答,從而逃逸免疫系統(tǒng)的攻擊作用,如使腫瘤浸潤的 CD8+CTLs和CD4+Th1細胞處于一種功能耗竭或無能狀態(tài),無法對腫瘤進行免疫監(jiān)視和清除[54]。因此誘導免疫活化、打破免疫耐受等已成為熱門的免疫治療方向,如免疫檢查點抑制劑[55]。有研究證明有些抗癌肽可以調節(jié)機體的免疫應答發(fā)揮其抗腫瘤作用。Chen等[56]報道TachyplesinⅠ能夠促使細胞表面的透明質烷和血清中補體途徑的關鍵成分C1q補體相互作用,并且激活其下游的C3和C4的裂解和沉積,以及C5b-9的形成,激活典型補體途徑從而破壞癌細胞的完整性。Chernysh等報道了來自紅頭麗蠅的抗菌肽alloferon可通過激活免疫應答抑制腫瘤生長。通過體外將小鼠淋巴細胞或人的血液單核細胞進行試驗,發(fā)現(xiàn)alloferon可激活自然殺傷 (NK) 細胞和干擾素 (IFN) 的表達[57]。Huang等[58]發(fā)現(xiàn)從比目魚豹鰨分離的抗癌肽GE33可以作為疫苗佐劑提升滅活膀胱癌細胞 (MBT-2) 的免疫原性,在小鼠體內顯著提高了CTL細胞和NK細胞數(shù)量以及特異性抗體水平等,證明了抗癌肽的免疫調節(jié)潛能。本課題組發(fā)現(xiàn)的抗癌肽HN-1在動物體內激活了CD4+T細胞和巨噬細胞在腫瘤中的浸潤,并且提高了腫瘤相關細胞因子在血清中的水平(圖3)。

圖3 抗癌肽HN-1的抗腫瘤機制

2.2.8 抑制腫瘤血管新生

新生血管形成與腫瘤侵襲和轉移息息相關,其為腫瘤組織提供氧氣和營養(yǎng),促進腫瘤細胞迅速增殖,同時為腫瘤的遠端轉移提供轉運[59]。因此靶向腫瘤新生血管生成或相關因子的抗癌類藥物研發(fā)具有重大意義。Mader等[60]通過實驗發(fā)現(xiàn)Lactoferricin B在體外通過阻止細胞生長因子 (bFGF) 和血管內皮生長因子 (VEGF165)與受體結合而抑制人臍靜脈內皮細胞 (HUVECs) 增殖,并且在C57BL/6小鼠體內抑制二者誘導的血管生成。Hou等[61]將人工設計抗菌肽與靶向給藥序列DGR相連接,發(fā)現(xiàn)其能夠與αvβ3+(腫瘤細胞過表達) 結合從而抑制血管的生成,充分證明了抗癌肽具有抑制血管新生的潛能。

3 總結與展望

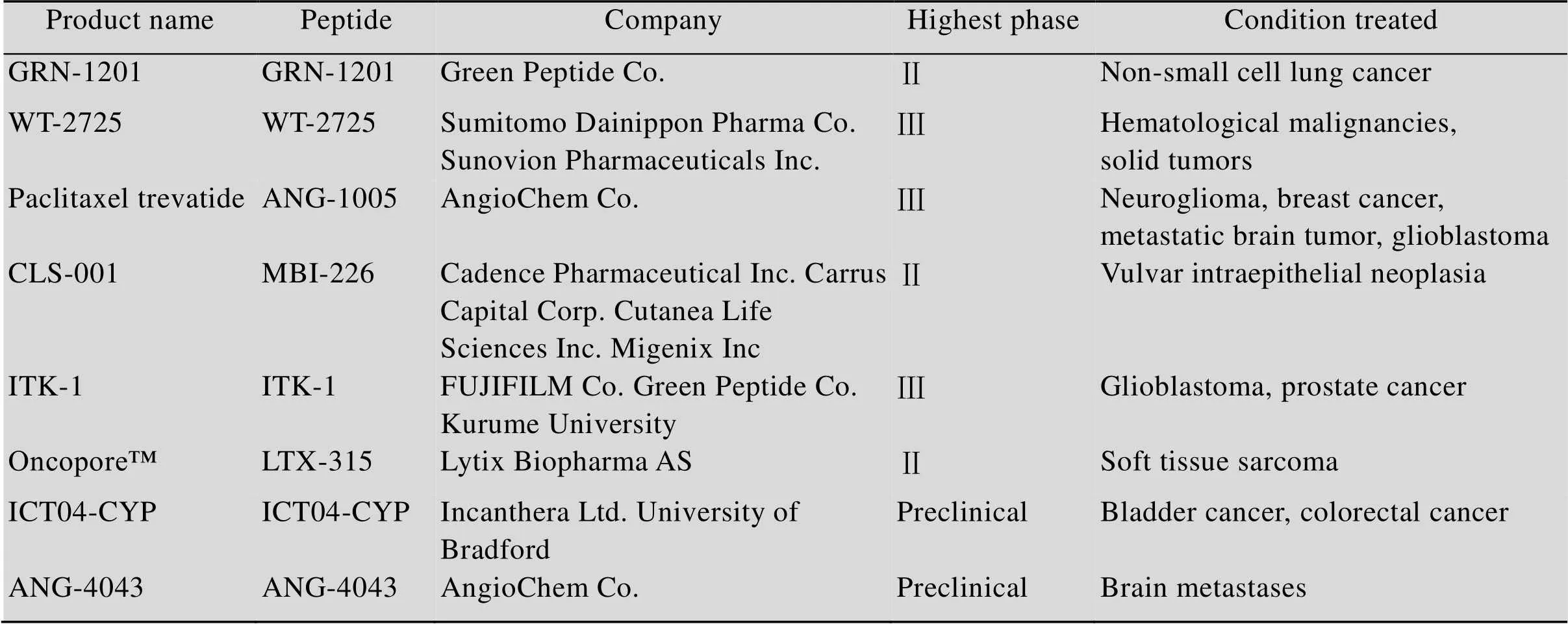

在過去的20年中,天然活性分子的多種治療潛能的持續(xù)發(fā)現(xiàn)引發(fā)了科學界的廣泛注意。抗癌肽由于其特殊的陽離子和兩親性的結構特征以及其眾多的抗癌機制,使其發(fā)揮了良好的抗癌作用或者增強化療藥物的效果,因而有望用于提高化療藥物的敏感性,同時減少對正常組織的毒副作用。目前已有大量不同治療目的肽類藥物進入臨床或批準上市,如表1所示,當前已有部分處于臨床試驗階段的抗癌肽,并取得了一定的效果[62]。但是抗癌肽的應用和研發(fā)仍面臨一些挑戰(zhàn),如合成成本較高、易被蛋白酶水解、易聚合、半衰期較短等[63]。因而當前抗癌肽的設計也集中于截短序列等,以降低成本[64];解決蛋白酶的水解問題,可以通過將天然氨基酸替換成非天然氨基酸,比如設計D-對映體肽、β2,2氨基酸替換、肽骨干環(huán)化、end-capping 如c-酰胺化、糖類coating等[65-67];提高半衰期可以將抗癌肽聚乙二醇修飾(PEGylation),結合到血清白蛋白或抗體片段等[68]。由此可見雖然抗癌肽在腫瘤治療方面有很好臨床應用價值,但是仍需克服這些缺陷和挑戰(zhàn),才能在腫瘤藥物治療領域有一席之地。因此,進一步確定和發(fā)現(xiàn)更多抗癌肽模板和抗腫瘤機制以及克服肽類藥物缺點的新方法對抗腫瘤臨床治療藥劑的發(fā)展具有重大意義。

表1 部分處于臨床試驗不同時期或臨床前研究的抗癌肽[62]

The search was carried out in the drug databases Pharmaprojects (www. pharmaprojects. com) and Pharmacodia (https: //data. pharmacodia. com/web/home/index).

[1] Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, et al. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin, 2018, 68(6): 394–424.

[2] Zugazagoitia J, Guedes C, Ponce S, et al. Current challenges in cancer treatment. Clin Ther, 2016, 38(7): 1551–1566.

[3] Thundimadathil J. Cancer treatment using peptides: current therapies and future prospects. J Amino Acids, 2012, 2012: 967347.

[4] Mitchell EP. Gastrointestinal toxicity of chemotherapeutic agents. Semin Oncol, 2006, 33(1): 106–120.

[5] Wijdeven RH, Pang B, Assaraf YG, et al. Old drugs, novel ways out: Drug resistance toward cytotoxic chemotherapeutics. Drug Resist Update, 2016, 28(1): 65–81.

[6] Schweizer F. Cationic amphiphilic peptides with cancer-selective toxicity. Eur J Pharmacol, 2009, 625(1/3): 190–194.

[7] Chan DI, Prenner EJ, Vogel HJ. Tryptophan- and arginine-rich antimicrobial peptides: Structures and mechanisms of action. Biochim Biophys Acta Biomembr, 2006, 1758(9): 1184–1202.

[8] Wei LY, Zhou C, Chen HR, et al. ACPred-FL: a sequence-based predictor using effective feature representation to improve the prediction of anti-cancer peptides. Bioinformatics, 2018, 34(23): 4007–4016.

[9] Hammami R, Fliss I. Current trends in antimicrobial agent research: chemo- and bioinformatics approaches. Drug Discov Today, 2010, 15(13/14): 540–546.

[10] Do N, Weindl G, Grohmann L, et al. Cationic membrane-active peptides-anticancer and antifungal activity as well as penetration into human skin. Experim Dermatol, 2014, 23(5): 326–331.

[11] Gaspar D, Veiga AS, Castanho MARB. From antimicrobial to anticancer peptides: a review. Front Microbiol, 2013, 4: 294.

[12] Shai Y. Mechanism of the binding, insertion and destabilization of phospholipid bilayer membranes by α-helical antimicrobial and cell non-selective membrane-lytic peptides. Biochim Biophys Acta Biomembr, 1999, 1462(1/2): 55–70.

[13] Gabernet G, Müller AT, Hiss JA, et al. Membranolytic anticancer peptides. Medchemcomm, 2016, 7(12): 2232–2245.

[14] Ehrenstein G, Lecar H. Electrically gated ionic channels in lipid bilayers. Quart Rev Biophys, 1977, 10(1): 1–34.

[15] Shai Y, Oren Z. From “carpet” mechanism to de-novo designed diastereomeric cell-selective antimicrobial peptides. Peptides, 2001, 22(10): 1629–1641.

[16] Sui SF, Wu H, Guo Y, et al. Conformational changes of melittin upon insertion into phospholipid monolayer and vesicle. J Biochem, 1994, 116(3): 482–487.

[17] Chen J, Guan SM, Sun W, et al. Melittin, the major pain-producing substance of bee venom. Neurosc Bull, 2016, 32(3): 265–272.

[18] Mulder KCL, Lima LA, Miranda VJ, et al. Current scenario of peptide-based drugs: the key roles of cationic antitumor and antiviral peptides. Front Microbiol, 2013, 4: 321.

[19] Wimley WC. How does melittin permeabilize membranes? Biophys J, 2018, 114(2): 251–253.

[20] Rozek T, Wegener KL, Bowie JH, et al. The antibiotic and anticancer active aurein peptides from the Australian Bell Frogsand-The solution structure of aurein 1.2. Eur J Biochem, 2000, 267(17): 5330–5341.

[21] Pouny Y, Rapaport D, Mor A, et al. Interaction of antimicrobial dermaseptin and its fluorescently labeled analogs with phospholipid membranes. Biochemistry, 1992, 31(49): 12416–12423.

[22] Chen HM, Wang W, Smith D, et al. Effects of the anti-bacterial peptide cecropin B and its analogs, cecropins B-1 and B-2, on liposomes, bacteria, and cancer cells. Biochim Biophys Acta Gen Subjects, 1997, 1336(2): 171–179.

[23] Chuang CM, Monie A, Wu AN, et al. Treatment with LL-37 peptide enhances antitumor effects induced by CpG oligodeoxynucleotides against ovarian cancer. Human Gene Therapy, 2009, 20(4): 303–313.

[24] Lehmann J, Retz M, Sidhu SS, et al. Antitumor activity of the antimicrobial peptide Magainin II against bladder cancer cell lines. Eur Urol, 2006, 50(1): 141–147.

[25] Doyle J, Brinkworth CS, Wegener KL, et al. nNOS inhibition, antimicrobial and anticancer activity of the amphibian skin peptide, citropin 1.1 and synthetic modifications. The solution structure of a modified citropin 1.1. Eur J Biochem, 2003, 270(6): 1141–1153.

[26] Won HS, Seo MD, Jung SJ, et al. Structural determinants for the membrane interaction of novel bioactive undecapeptides derived from gaegurin 5. J Med Chem, 2006, 49(16): 4886–4895.

[27] Matsuzaki K, Sugishita KI, Harada M, et al. Interactions of an antimicrobial peptide, magainin 2, with outer and inner membranes of Gram-negative bacteria. Biochim Biophys Acta Biomembr, 1997, 1327(1): 119–130.

[28] Takeshima K, Chikushi A, Lee KK, et al. Translocation of analogues of the antimicrobial peptides magainin and buforin across human cell membranes. J Biol Chem, 2003, 278(2): 1310–1315.

[29] Neuhaus CS, Gabernet G, Steuer C, et al. Simulated molecular evolution for anticancer peptide design. Angew Chem Int Ed, 2019, 58(6): 1674–1678.

[30] Pino-Angeles A, Leveritt III JM, Lazaridis T. Pore structure and synergy in antimicrobial peptides of the magainin family. PLoS Comput Biol, 2016, 12(1): e1004570.

[31] Nagata S. Apoptosis and clearance of apoptotic cells. Ann Rev Immunol, 2018, 36: 489–517.

[32] Soengas MS, Lowe SW. Apoptosis and melanoma chemoresistance. Oncogene, 2003, 22(20): 3138–3151.

[33] Lee HS, Park CB, Kim JM, et al. Mechanism of anticancer activity of buforin IIb, a histone H2A-derived peptide. Cancer Lett, 2008, 271(1): 47–55.

[34] Chen YX, Xu XM, Hong SG, et al. RGD-tachyplesin inhibits tumor growth. Cancer Res, 2001, 61(6): 2434–2438.

[35] Giampazolias E, Tait SWG. Caspase-independent cell death: An anti-cancer double whammy. Cell Cycle, 2018, 17(3): 269–270.

[36] Ren SX, Cheng ASL, To KF, et al. Host immune defense peptide LL-37 activates caspase-independent apoptosis and suppresses colon cancer. Cancer Res, 2012, 72(24): 6512–6523.

[37] Zhang SY, Guo HH, Shi F, et al. Hainanenins: A novel family of antimicrobial peptides with strong activity from Hainan cascade-frog,. Peptides, 2012, 33(2): 251–257.

[38] Li QF, Ouyang GL, Peng XX, et al. Effects of tachyplesin on the regulation of cell cycle in human hepatocarcinoma SMMC-7721 cells. World J Gastroenterol, 2003, 9(3): 454–458.

[39] Zhao YL, Cai XT, Ye TM, et al. Analgesic-antitumor peptide inhibits proliferation and migration of SHG-44 human malignant glioma cells. J Cell Biochem, 2011, 112(9): 2424–2434.

[40] Liao WZ, Zhang R, Dong CB, et al. Novel walnut peptide-selenium hybrids with enhanced anticancer synergism: facile synthesis and mechanistic investigation of anticancer activity. Int J Nanomed, 2016, 11: 1305–1321.

[41] Dielschneider RF, Henson ES, Gibson SB. Lysosomes as oxidative targets for cancer therapy. Oxidat Med Cell Long, 2017, 2017: 3749157.

[42] Adak A, Mohapatra S, Mondal P, et al. Design of a novel microtubule targeted peptide vesicle for delivering different anticancer drugs. Chem Commun, 2016, 52(48): 7549–7552.

[43] Singh R, Sharma M, Joshi P, et al. Clinical status of anti-cancer agents derived from marine sources. Anti-Cancer Agent Med Chem, 2008, 8(6): 603–617.

[44] Held-Kuznetsov V, Rotem S, Assaraf YG, et al. Host-defense peptide mimicry for novel antitumor agents. FASEB J, 2009, 23(12): 4299–4307.

[45] Cui CC, Merritt R, Fu LW, et al. Targeting calcium signaling in cancer therapy. Acta Pharm Sin B, 2017, 7(1): 3–17.

[46] Wang C, Chen TY, Zhang N, et al. Melittin, a major component of bee venom, sensitizes human hepatocellular carcinoma cells to tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL)- induced apoptosis by activating CaMKII-TAK1-JNK/ p38 and inhibiting IκBα Kinase-NFκB. J Biol Chem, 2009, 284(6): 3804–3813.

[47] Risso A, Braidot E, Sordano MC, et al. BMAP-28, an antibiotic peptide of innate immunity, induces cell death through opening of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore. Mol Cell Biol, 2002, 22(6): 1926–1935.

[48] Gower WR Jr, Vesely BA, Alli AA, et al. Four peptides decrease human colon adenocarcinoma cell number and DNA synthesis via cyclic GMP. Int J Gastrointest Cancer, 2005, 36(2): 77–87.

[49] Hariton-Gazal E, Feder R, Mor A, et al. Targeting of nonkaryophilic cell-permeable peptides into the nuclei of intact cells by covalently attached nuclear localization signals. Biochemistry, 2002, 41(29): 9208–9214.

[50] Levine B, Abrams J. p53: The Janus of autophagy? Nat Cell Biol, 2008, 10(6): 637–639.

[51] Katheder NS, Khezri R, O’Farrell F, et al. Microenvironmental autophagy promotes tumour growth. Nature, 2017, 541(7637): 417–420.

[52] Ren SX, Shen J, Cheng AS, et al. FK-16 derived from the anticancer peptide LL-37 induces caspase- independent apoptosis and autophagic cell death in colon cancer cells. PLoS ONE, 2013, 8(5): e63641.

[53] Drake CG, Jaffee E, Pardoll DM. Mechanisms of immune evasion by tumors. Adv Immunol, 2006, 90: 51–81.

[54] Fuller MJ, Khanolkar A, Tebo AE, et al. Maintenance, loss, and resurgence of T cell responses during acute, protracted, and chronic viral infections. J Immunol, 2004, 172(7): 4204–4214.

[55] Byun DJ, Wolchok JD, Rosenberg LM, et al. Cancer immunotherapy-immune checkpoint blockade and associated endocrinopathies. Nat Rev Endocrinol, 2017, 13(4): 195–207.

[56] Chen JG, Xu XN, Underhfll CB, et al. Tachyplesin activates the classic complement pathway to kill tumor cells. Cancer Res, 2005, 65(11): 4614–4622.

[57] Chernysh S, Kim SI, Bekker G, et al. Antiviral and antitumor peptides from insects. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 2002, 99(20): 12628–12632.

[58] Huang HN, Rajanbabu V, Pan CY, et al. A cancer vaccine based on the marine antimicrobial peptide pardaxin (GE33) for control of bladder-associated tumors. Biomaterials, 2013, 34(38): 10151–10159.

[59] Mafu TS, September AV, Shamley D. The potential role of angiogenesis in the development of shoulder pain, shoulder dysfunction, and lymphedema after breast cancer treatment. Cancer Manag Res, 2018, 10: 81–90.

[60] Mader JS, Smyth D, Marshall J, et al. Bovine lactoferricin inhibits basic fibroblast growth factor- and vascular endothelial growth factor 165-induced angiogenesis by competing for heparin-like binding sites on endothelial cells. Am J Pathol, 2006, 169(5): 1753–1766.

[61] Hou L, Zhao XH, Wang P, et al. Antitumor activity of antimicrobial peptides containingDGRC in CD13 negative breast cancer cells. PLoS ONE, 2013, 8(1): e53491.

[62] Leite ML, Da Cunha NB, Costa FF, et al. Antimicrobial peptides, nanotechnology, and natural metabolites as novel approaches for cancer treatment. Pharmacol Ther, 2018, 183: 160–176.

[63] Fosgerau K, Hoffmann T. Peptide therapeutics: current status and future directions. Drug Discov Today, 2015, 20(1): 122–128.

[64] Domalaon R, Findlay B, Ogunsina M, et al. Ultrashort cationic lipopeptides and lipopeptoids: Evaluation and mechanistic insights against epithelial cancer cells. Peptides, 2016, 84: 58–67.

[65] de La Fuente-Nú?ez C, Reffuveille F, Mansour SC, et al. D-enantiomeric peptides that eradicate wild-type and multidrug-resistant biofilms and protect against lethalinfections. Chem Biol, 2015, 22(9): 1280–1282.

[66] T?rfoss V, Ausbacher D, Cavalcanti-Jacobsen C, et al. Synthesis of anticancer heptapeptides containing a unique lipophilic2,2-amino acid building block. J Pept Sci, 2012, 18(3): 170–176.

[67] Svenson J, Stensen W, Brandsdal BO, et al. Antimicrobial peptides with stability toward tryptic degradation. Biochemistry, 2008, 47(12): 3777–3788.

[68] Kelly GJ, Kia AFA, Hassan F, et al. Polymeric prodrug combination to exploit the therapeutic potential of antimicrobial peptides against cancer cells. Org Biomol Chem, 2016, 14(39): 9278–9286.

Progress in the mechanisms of anticancer peptides

Xue Qiao1, Yipeng Wang2, and Haining Yu1

1 School of Biological Engineering, Dalian University of Technology, Dalian 116024, Liaoning, China 2 School of Life Sciences, Suzhou University, Suzhou 215123, Jiangsu, China

In recent years, cancer has become a major concern in relation to human morbidity and mortality. Anticancer peptides (ACPs) are the bioactive peptide with antitumor activity and found in many organisms, including mammals, amphibians, insects, plants and microorganisms. ACPs have been suggested as promising agents for antitumor therapy due to their numerous advantages over traditional chemical agents such as low molecular masses, relatively simple structures, greater tumor selectivity, fewer adverse reactions, ease of absorption, a variety of routes of administration and low risk for inducing multi-drug resistance. Combining with the related research in our group, we summarized the mechanisms of ACPs to provide some directions for research and development of peptide-based anticancer drugs.

anticancer peptides, membranolytic mechanism, non-membranolytic mechanisms, novel anti-tumor drug

January 17, 2019;

April 16, 2019

Supported by: National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 31872223, 31772455).

Haining Yu. Tel/ Fax: +86-411-84708850; E-mail: joannyu@live.cn

國家自然科學基金(Nos. 31872223, 31772455) 資助。

2019-05-27

http://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/11.1998.Q.20190524.1603.002.html

喬雪, 王義鵬, 于海寧. 抗癌肽的作用機制研究進展. 生物工程學報, 2019, 35(8): 1391–1400.Qiao X, Wang YP, Yu HN. Progress in the mechanisms of anticancer peptides. Chin J Biotech, 2019, 35(8): 1391–1400.

(本文責編 陳宏宇)