同種雄性競爭對手的存在對星豹蛛雄蛛求偶和交配行為的影響

陳 博,文樂雷,趙菊鵬,梁宏合,陳 建,焦曉國,*

1 湖北大學生命科學學院,行為生態與進化研究中心,湖北生物資源綠色轉化協同創新中心, 武漢 430062 2 廣東出入境檢驗檢疫局檢驗檢疫技術中心,廣州 510623 3 廣西壯族自治區亞熱帶作物研究所,南寧 530002

?

同種雄性競爭對手的存在對星豹蛛雄蛛求偶和交配行為的影響

陳 博1,文樂雷1,趙菊鵬2,梁宏合3,陳 建1,焦曉國1,*

1 湖北大學生命科學學院,行為生態與進化研究中心,湖北生物資源綠色轉化協同創新中心, 武漢 430062 2 廣東出入境檢驗檢疫局檢驗檢疫技術中心,廣州 510623 3 廣西壯族自治區亞熱帶作物研究所,南寧 530002

越來越多的研究發現,雄性產生精子(精液)也需付出代價。雄性除了依據配偶質量和競爭對手的競爭強度適應性調整生殖投入外,雄性在求偶和交配行為上也相應產生適應性反應,求偶和交配行為具有可塑性。目前雄性求偶和交配行為可塑性研究主要集中于雌性多次交配的類群中,在雌性單次交配的類群中研究甚少。以雌蛛一生只交配一次而雄蛛可多次交配的星豹蛛為研究對象,比較:(1)前一雄性拖絲上信息物質對后續雄蛛求偶和交配行為的影響,(2)雌雄不同性比對雄蛛求偶和交配行為的影響。研究結果表明,星豹蛛前一雄蛛拖絲上的信息物質對后續雄蛛求偶潛伏期、求偶持續時間和交配持續時間都沒有顯著影響,但前一雄蛛拖絲上的信息物質對后續雄蛛求偶強度有顯著抑制作用。同時,性比對星豹蛛雄蛛求偶和交配行為都沒有顯著影響。可見,星豹蛛雄蛛對同種雄性拖絲上的化學信息可產生求偶行為的適應性調整,而對性比不產生適應性反應。

星豹蛛;單次交配;求偶交配;適應性反應;可塑性行為

根據Trivers的性選擇理論,雌性在生殖上投資通常大于雄性;“殷勤”的雄性嘗試盡可能與多個雌性交配以提高自己的生殖成功率,而“挑剔”的雌性只能依靠加速產卵和產仔來提高生殖成功率[1]。對雄性動物而言,雌性只是它們相互競爭的稀缺資源,從而驅使雄性個體為爭奪稀缺雌性而展開激烈競爭[1]。

對多次交配的動物而言,動物的性選擇包括交配前的性選擇和交配后的性選擇[2- 4]。交配后性選擇又分為雌性的隱秘選擇[5]和雄性的精子競爭[2- 4]。雄性產生精子也需付出代價[4]。雄性為獲得最大生殖潛力,依據配偶質量和對手的競爭強度策略性地調整當前生殖投入,包括精子(精液)質量和精子數量[2- 4]。雄性精子競爭又可以進一步分為精子競爭風險模型和精子競爭強度模型[2- 4]。當感知周圍存在同種競爭對手或競爭對手遺留化學信息的情況下,雄性通常提高求偶強度和交配持續時間,以增加當前的生殖投入[4,6- 13]。雄性一般依據環境中其它雄性遺留的化學信息來評價交配的競爭風險[6- 13]。此外,性比也是影響動物性選擇強度的一個重要因子[6,14- 18]。當外界性比偏重雌性時,雄性通常降低當前的生殖投入。相反,當外界性比偏重雄性時,雄性通常增加當前的生殖投入。行為上主要表現為雄性求偶和交配行為的適應性調整[6,14-18]。

目前雄性策略性求偶和交配行為及生殖投入研究主要集中于多次交配物種中[2- 4,6],在單次交配物種中研究甚少[19-20]。對一生只進行單次交配的動物而言,只有交配前性選擇起作用。由于其一生只能交配一次,雌性對雄性配偶的選擇非常慎重,通常優先選擇競爭力強的“心儀”雄性。對雄性而言,其只有準確搜尋和定位未交配雌性時,才可能獲得交配的機會。因此,雄性通常借助環境中雌性留下能反映雌性交配狀態的化學信息對潛在配偶進行評價。

在蜘蛛中,雄蛛通過觸肢上化學感受器感知蛛網和拖絲上化學信息物質,對潛在對象的物種、性別、交配狀態和是否成熟進行準確辨別[21-24]。星豹蛛Pardosaastrigera是中國廣為分布的一種游獵型狼蛛。星豹蛛雌蛛一生只交配一次,而雄蛛可多次交配[25]。當星豹蛛雄蛛面對雌蛛時, 雄蛛在雌蛛面前展現復雜的求偶行為。第一對步足上下伸展和整個身體作俯臥撐式運動是星豹蛛雄蛛典型的求偶行為[25]。僅提供成熟未交配雌蛛的拖絲,雌蛛拖絲上化學信息物質同樣能激起雄蛛上述典型的求偶行為[24]。先前研究發現,星豹蛛雄性拖絲上的信息物質抑制后續同種雄性的求偶行為,并且雄蛛求偶強度與交配成功率正相關[26]。

本研究以雌蛛一生只交配一次而雄蛛可多次交配的星豹蛛為研究對象,比較(1)前一雄蛛拖絲上信息物質對后續雄蛛求偶和交配行為的影響,(2)雌雄不同性比對星豹蛛雄蛛求偶和交配行為的影響。首次在雌性單配制狼蛛中驗證雄性在面對不同競爭風險時,其是否具有適應性調整自身求偶和交配行為的能力。

1 材料與方法

1.1 實驗材料

星豹蛛Pardosaastrigera(L. Koch 1877) 于2014年11月采自湖北省武漢市馬鞍山森林公園。當地星豹蛛以亞成蛛越冬,11月正是星豹蛛亞成蛛發生的高峰期。采回后在實驗室培養箱內飼養,培養箱溫度控制在25℃,14L:10D光照。蜘蛛放入玻璃試管中單頭飼養,試管底部用一塊蘸水的海綿保濕,每星期飼喂2次,每次提供20—30頭黑腹果蠅成蟲。星豹蛛亞成蛛蛻皮后供實驗用。實驗前24h禁止喂食。

1.2 實驗裝置、內容與方法

1.2.1 星豹蛛雄蛛拖絲對后續雄蛛求偶和交配行為的影響

用試管把成熟6d沒有交配的星豹蛛雌蛛輕輕引入鋪有潔凈濾紙的培養皿(直徑9 cm,培養皿蓋內側正上方放一蘸水的棉球保濕,實驗室溫度控制25℃,14L∶10D光照)中,收集雌蛛拖絲2h。2h后把培養皿中雌蛛轉移,然后把收集有雌蛛拖絲的培養皿隨機分為3組。第1組(NM:只有雌蛛拖絲,沒有雄蛛拖絲):把雌蛛引入培養皿,讓其適應2 min,然后引入1只成熟沒有交配的雄蛛,觀察其求偶和交配行為;第2組(OM:既有雌蛛拖絲,也有雄蛛自身的拖絲):把成熟沒有交配的一只雄蛛輕輕引入收集有雌蛛拖絲的培養皿中,讓其自由活動30 min,收集雄蛛的拖絲,然后轉移雄蛛。接著把單只雌蛛引入培養皿,讓其適應2 min,最后把先前雄蛛放入培養皿,觀察其求偶和交配行為;第3組(AM:既有雌蛛拖絲,也有其它雄蛛的拖絲):把成熟沒有交配的1只雄蛛輕輕引入收集有雌蛛拖絲的培養皿中,讓其自由活動30 min,收集雄蛛的拖絲,然后轉移雄蛛。接著把雌蛛引入培養皿,讓其適應2 min,最后把另一不同雄蛛放入培養皿,觀察其求偶和交配行為。從引入雄蛛開始記時,直至雌雄蛛成功完成交配,如果沒有成功交配,則只持續記錄30 min。分別記錄下述指標:(1)雄蛛求偶潛伏時間,即從引入雄蛛開始到雄蛛在培養皿中表現典型求偶行為止;(2)雄蛛求偶持續時間,即30 min內雄蛛用于求偶總時間;(3)雄蛛第一對步足伸展頻率,雄蛛整個求偶期內,雄蛛平均每秒第一對步足伸展次數。(4)雄蛛身體振動頻率,雄蛛整個求偶期內,雄蛛平均每秒身體作“俯臥撐”式振動次數。(5)交配持續時間(Mating duration),即雄蛛將觸肢器插入雌蛛外雌器開始,至雌雄蛛分開。如果雄蛛引入后30 min 內不活動,則該數據剔除,不參與統計。每完成一組實驗,用酒精擦拭培養皿,干后再用。

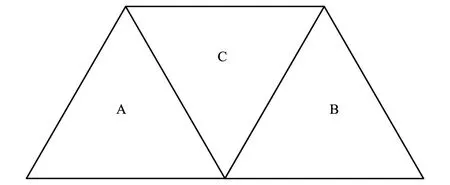

圖1 不同性比對星豹蛛求偶和交配行為影響實驗裝置圖 Fig.1 Construction for determining the effect of sex ratio of the wolf spider Pardosa astrigera on male courtship and mating

1.2.2 星豹蛛不同性比對雄蛛交配持續時間的影響

實驗裝置(圖1)由透明玻璃組成,A、B和C為邊長為6 cm的等邊三角形,C為雌雄交配區域,底部墊有潔凈濾紙,A和B為放置單頭星豹蛛的區域。實驗前首先在交配裝置C區底部墊上潔凈的濾紙,用試管把成熟日齡為6d沒有交配的星豹蛛雌蛛輕輕引入C區,收集雌蛛拖絲2h,然后輕輕引入成熟沒有交配的雄蛛,同時在A和B區分別引入單只成熟沒有交配的雌蛛或雄蛛。交配裝置側面放一蘸水的棉球保濕,實驗室溫度控制25℃,光照14L∶10D。設置為3個處理。第1個處理為1雌1雄:A和B都空置;第2個處理為3雌1雄:C區一旦引入雄蛛,立刻在A和B區分別放置一只雌蛛;第3個處理為3雄1雌:C區一旦引入雄蛛,立刻在A和B區分別放置一只雄蛛。依次記錄不同處理交配裝置C區中雄蛛求偶和交配行為。用酒精擦拭交配裝置內壁,待酒精揮發后再次使用。

1.3 數據分析

采用單因素方差分析(SPSS 16統計軟件) 統計星豹蛛求偶和交配行為差異,如差異顯著,進一步用Tukey測驗比較不同處理之間的差異。數據統一采用 Mean + SE 顯示。

2 結果與分析

2.1 星豹蛛雄蛛拖絲對后續雄蛛求偶和交配行為的影響

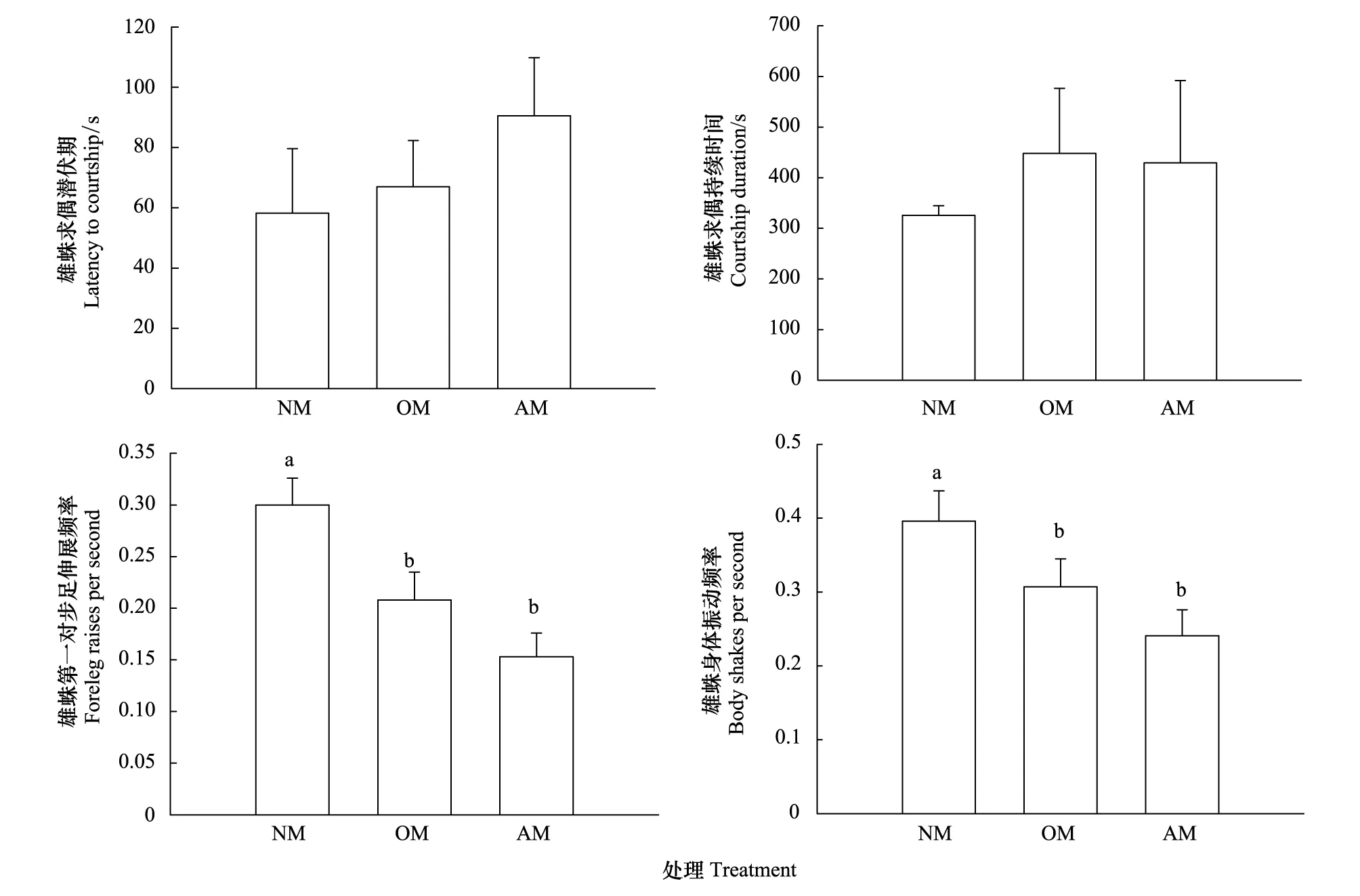

在不同處理中,雄蛛的求偶行為比較結果見圖2。不同處理對雄蛛求偶潛伏期(圖2:F2,57=0.539,P=0.672)和求偶持續時間(圖2:F2,57=0.218,P=0.805)都沒有顯著影響。但不同處理對星豹蛛雄蛛第一對步足伸展頻率(圖2:F2,57=4.418,P=0.016)和身體振動頻率(圖2:F2,57=4.219,P=0.020)都有顯著影響。NM雄蛛第一對步足伸展頻率和身體振動頻率都顯著高于OM和AM雄蛛,而后二者之間沒有顯著差異。

圖2 星豹蛛不同雄蛛拖絲對后續雄蛛求偶行為(Mean + SE)的影響 Fig.2 Effects of dragline from different male wolf spider Pardosa astrigera on courtship behaviour of subsequent malesNM:無雄蛛拖絲 No male dragline;OM: 同一雄蛛拖絲male own dragline;AM: 不同雄蛛拖絲 Another male dragline;不同英文字母示差異顯著

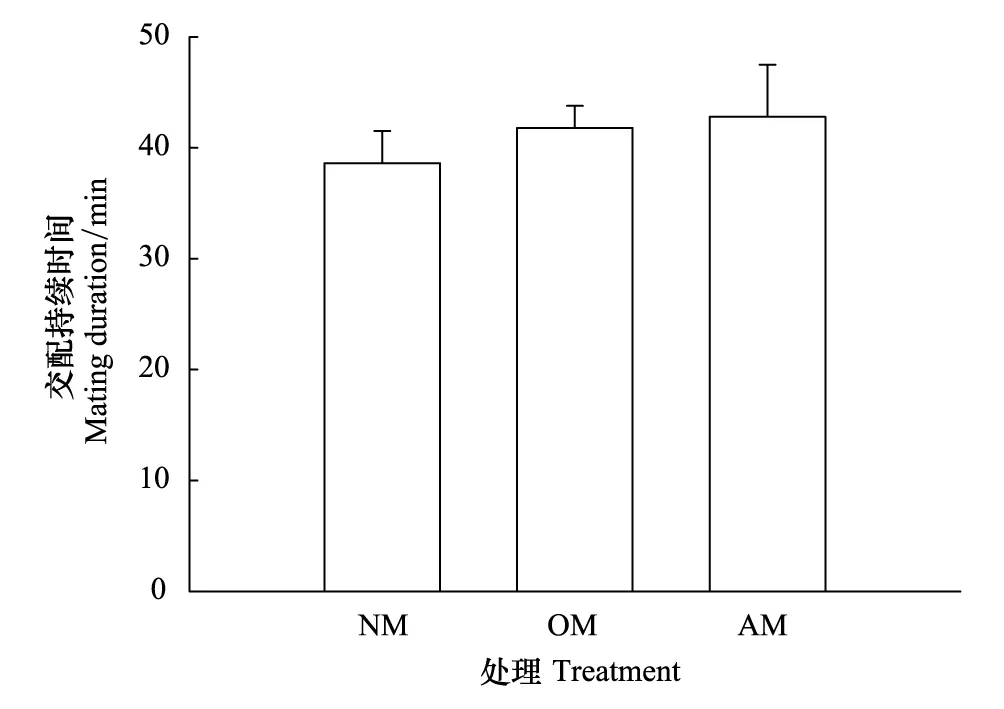

在NM、OM和AM 3種不同交配處理中,雄蛛交配持續時間都沒有顯著差異(圖3:F2,57=0.416,P=0.662)。

圖3 星豹蛛不同雄蛛拖絲對后續雄蛛交配持續時間(Mean + SE)的影響Fig.3 Effects of dragline from different male wolf spider Pardosa astrigera on mating duration of subsequent males

2.2 星豹蛛不同性比對雄蛛求偶和交配行為的影響

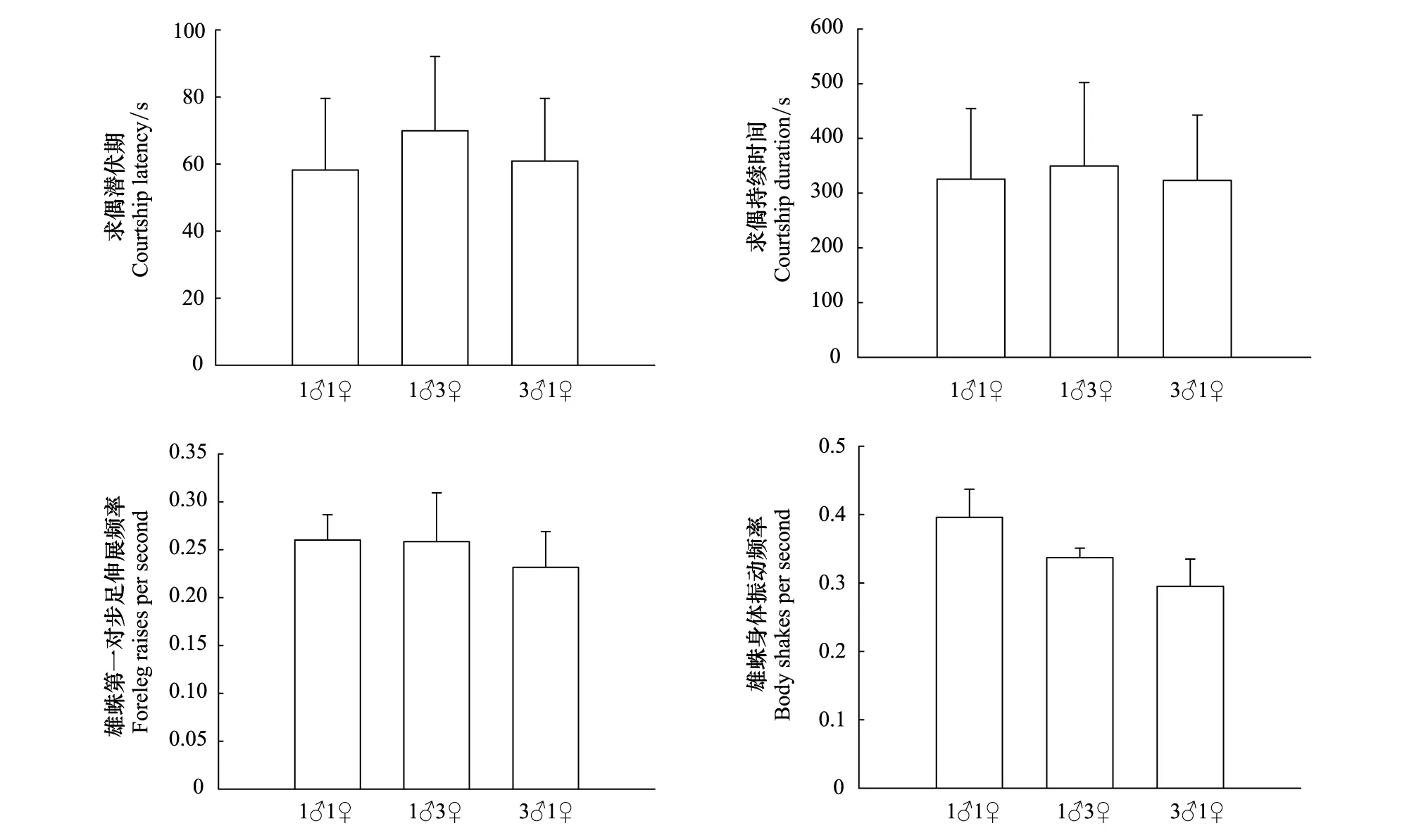

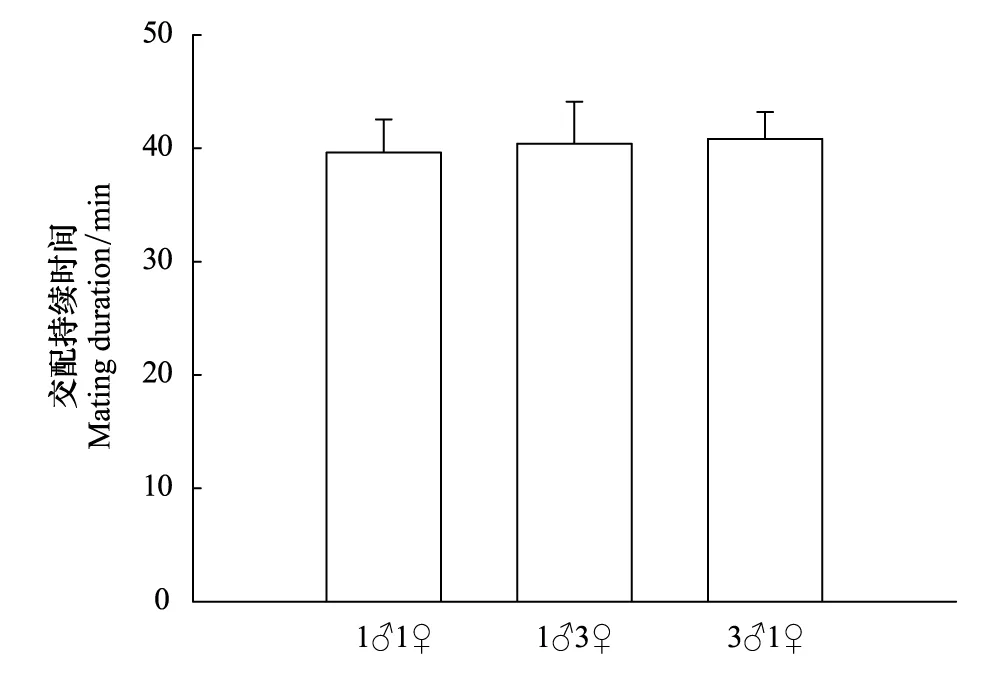

在面對不同性比星豹蛛成蛛時,雄蛛的求偶和交配行為比較結果見圖4。不同性比對雄蛛求偶潛伏期(圖4:F2,57=0.160,P=0.854)和求偶持續時間(圖4:F2,57=0.012,P=0.988)都沒有顯著影響。同時不同性比對星豹蛛雄蛛第一對步足伸展頻率(圖4:F2,57=0.165,P=0.848)和身體振動頻率(圖4:F2,57=1.281,P=0.286)也都沒有顯著影響。同樣,性比對雄蛛交配持續時間也沒有顯著影響(圖5:F2,57=0.381,P=0.685)。

3 討論

圖4 星豹蛛不同性比對雄蛛求偶行為(Mean + SE)的影響Fig.4 Effects of sex ratio of the wolf spider Pardosa astrigera on male courtship behaviour

圖5 星豹蛛不同性比對雄蛛交配持續時間(Mean + SE)的影響 Fig.5 Effects of sex ratio of the wolf spider Pardosa astrigera on male mating duration

已有研究表明,雄性除產生精子需付出代價外,與交配相關的其它行為,如求偶和交配也需付出代價[27- 31]。雄性為實現生殖潛力最大化,必需依配偶的質量和競爭對手的競爭強度適應性調整其求偶和交配行為。Bretman等把雄性在面臨其它雄性競爭對手時表現的可塑性性行為分為交配前、交配中和交配后行為3類。交配前行為主要指雄性的求偶行為,交配過程中行為指交配持續時間,而交配后行為主要指配偶的守護行為[6]。對多配制動物,雄性通常表現上述3類可塑性行為[6];而對單配制動物,研究甚少,少數研究表明其只表現交配前和交配中可塑性行為[19-20]。雄性通常依據環境中其它雄性遺留的化學信息來評價交配競爭風險[6- 13]。Aragón研究發現雄蠑螈Lissotritonboscai在感知水體中有其它雄性化學信息時,其降低求偶行為[7]。雄性蟋蟀Gryllusbimaculatus在有其它雄性化學信息存在條件下,其會增強其求偶行為[12]。可見在不同物種中,雄性對外界環境中其它雄性的化學信息會產生不同反應。該差異性反應可能與雌性交配模式和精子優先模式有關。對于單配制雌性,當雄性感知外界環境中雄性的化學信息時,降低其求偶是適宜的。對于多配制雌性,雄性求偶行為的調整與雄性精子優先模式有關。如果第一只雄性精子優先受精,當雄性感知外界環境中其它雄性存在信息時,降低其求偶是適宜的;相反,如果最后一只雄性精子優先受精,當雄性感知外界環境中其它雄性信息時,增強其求偶行為是適宜的。在不同狼蛛中,雄蛛求偶強度越大,其交配成功率越高[26,31]。但求偶強度越大,其能量付出也越大,壽命顯著縮短[28- 30]。當前的研究發現,前一雄蛛拖絲上化學信息物質抑制后續雄蛛的求偶強度,即便提供同等質量的成熟未交配雌蛛。可見本文的研究結果與Aragón的研究結論一致[7],也與Ayyagari 和 Tietjen 對狼蛛Schizocosaocreata的研究結果一致[32]。這一結果與星豹蛛雌蛛一生只交配一次的交配模式也是吻合的。

研究結果還發現,雄蛛在自己拖絲上和在其它雄蛛拖絲上求偶強度沒有顯著差異,可見雄蛛不能辨別雄性拖絲來自于自己還是來自其它雄蛛的拖絲。在野外,雄蛛在通過雌蛛釋放的拖絲上信息物質追蹤定位雌蛛過程中,雌蛛很可能已與其它同種雄蛛完成交配。因此雄蛛在追蹤定位雌蛛過程中,如果感知雌蛛拖絲上遺留有其它雄蛛拖絲信息物質時,其降低求偶強度是一種適應性行為。降低求偶強度不但可以節省能量,而且可以避免無效追蹤而喪失追蹤其它適宜配偶的機會。

本研究發現,在星豹蛛雄性競爭對手信息存在條件下,無論是化學刺激(雄蛛拖絲),還是視覺刺激(偏向雄性的性比),雄蛛交配持續時間一直保持固定不變。可見,與多配制物種不同,星豹蛛雄蛛交配持續時間不具有適應性改變的能力。Bretman等認為,對單配制物種,雄性交配行為可塑性低;相反對多配制物種,雄性交配行為可塑性高[6]。可見本結論與Bretman等的預測結果也一致。但Lizé等研究發現單配制的果蠅Drosophilasubobscura存在競爭對手時,雄性意外地延長交配持續時間[20]。Lizé等據此推斷Drosophilasubobscura單配制起源于多配制。相反,Arnqvist在鱗翅目、雙翅目和鞘翅目中采用系統發育方法證實多配制起源于單配制[33]。關于單配制和多配制的起源和進化方向一直是一個懸而未決的問題。星豹蛛雌蛛單配制是祖征?還是由多配制演化而來值得做進一步研究。在野外自然條件下,星豹蛛雌雄性比接近1,雄蛛比雌蛛早成熟,加之雄蛛可以多次交配而雌蛛一生只交配一次,因此雄蛛之間為獲得交配機會而產生很強的交配前競爭[34]。可以推測雄蛛很少有多次交配的機會,甚至很多雄蛛根本就沒有交配的機會。因此雄蛛一旦有幸獲得交配機會,將其生殖投資最大地投入到當前的交配是其適應性選擇。因此,雄性交配持續時間保持不變也可能是一種適應性行為。

[1] Trivers R L. Parental investment and sexual selection//Campbell B, ed. Sexual Selection and the Descent of Man. Chicago: Aldine, 1972.

[2] Kelly C D, Jennions M D. Sexual selection and sperm quantity: meta-analyses of strategic ejaculation. Biological Reviews, 2011, 86(4): 863- 884.

[3] Parker G A, Pizzari T. Sperm competition and ejaculate economics. Biological Reviews, 2010, 85(4): 897- 934.

[4] Wedell N, Gage M J G, Parker G A. Sperm competition, male prudence and sperm-limited females. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 2002, 17(7): 313- 320.

[5] Eberhard W G. Female Control: Sexual Selection by Cryptic Female Choice. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1996.

[6] Bretman A, Gage M J G, Chapman T. Quick-change artists: male plastic behavioural responses to rivals. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 2011, 26(9): 467- 473.

[7] Aragón P. Conspecific male chemical cues influence courtship behaviour in the male newtLissotritonboscai. Behaviour, 2009, 146(8): 1137- 1151.

[8] Carazo P, Font E, Alfthan B. Chemosensory assessment of sperm competition levels and the evolution of internal spermatophore guarding. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 2007, 274(1607): 261- 267.

[9] Friberg U. Male perception of female mating status: its effect on copulation duration, sperm defence and female fitness. Animal Behaviour, 2006, 72(6): 1259- 1268.

[10] Lane S M, Solino J H, Mitchell C, Blount J D, Okada K, Hunt J, House C M. Rival male chemical cues evoke changes in male pre- and post-copulatory investment in a flour beetle. Behavioral Ecology, 2015, 26(4): 1021- 1029.

[11] Lecomte C, Thibout E, Pierre D, Auger J. Transfer, perception, and activity of male pheromone ofAcrolepiopsisassectellawith special reference to conspecific male sexual inhibition. Journal of Chemical Ecology, 1998, 24(4): 655- 671.

[12] Lyons C, Barnard C J. A learned response to sperm competition in the field cricket,Gryllusbimaculatus(de Geer). Animal Behaviour, 2006, 72(3): 673- 680.

[13] Thomas M L, Simmons L W. Male-derived cuticular hydrocarbons signal sperm competition intensity and affect ejaculate expenditure in crickets. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 2009, 276(1655): 383- 388.

[14] Bretman A, Fricke C, Chapman T. Plastic responses of maleDrosophilamelanogasterto the level of sperm competition increase male reproductive fitness. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 2009, 276(1662): 1705- 1711.

[15] Bretman A, Fricke C, Hetherington P, Stone R, Chapman T. Exposure to rivals and plastic responses to sperm competition inDrosophilamelanogaster. Behavioral Ecology, 2010, 21(2): 317- 321.

[16] Bretman A, Westmancoat J D, Gage M J G, Chapman T. Costs and benefits of lifetime exposure to mating rivals in maleDrosophilamelanogaster. Evolution, 2013, 67(8): 2413- 2422.

[17] Bretman A, Westmancoat J D, Gage M J G, Chapman T. Individual plastic responses by males to rivals reveal mismatches between behaviour and fitness outcomes. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 2012, 279(1739): 2868- 2876.

[18] García-González F, Gomendio M. Adjustment of copula duration and ejaculate size according to the risk of sperm competition in the golden egg bug (Phyllomorphalaciniata). Behavioral Ecology, 2004, 15(1): 23- 30.

[19] Lizé A, Price T A R, Heys C, Lewis Z, Hurst G D D. Extreme cost of rivalry in a monandrous species: male-male interactions result in failure to acquire mates and reduced longevity. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 2014, 281(1786): 20140631.

[20] Lizé A, Doff R J, Smaller E A, Lewis Z, Hurst G D D. Perception of male-male competition influencesDrosophilacopulation behaviour even in species where females rarely remate. Biology Letters, 2012, 8(1): 35- 38.

[21] Baruffaldi L, Costa F G. Changes in male sexual responses from silk cues of females at different reproductive states in the wolf spiderSchizocosamalitiosa. Journal of Ethology, 2010, 28(1): 75- 85.

[22] Gaskett A C. Spider sex pheromones: emission, reception, structures, and functions. Biological Reviews, 2007, 82(1): 27- 48.

[23] Roberts J A, Uetz G W. Information content of female chemical signals in the wolf spider,Schizocosaocreata: male discrimination of reproductive state and receptivity. Animal Behaviour, 2005, 70(1): 217- 223.

[24] 吳俊, 焦曉國, 陳建, 彭宇, 劉鳳想, 王振華. 雌星豹蛛性信息素的行為學證據. 動物學報, 2007, 53(6): 994- 999.

[25] 吳俊, 焦曉國, 陳建, 彭宇, 劉鳳想. 星豹蛛求偶和交配行為. 動物學雜志, 2008, 43(2): 9- 12.

[26] Xiao R, Chen B, Wang Y C, Lu M, Chen J, Li D Q, Yun Y L, Jiao X G. Silk-mediated male courtship effort in the monandrous wolf spiderPardosaastrigera(Araneae: Lycosidae). Chemoecology, 2015, 25(6): 285- 292.

[27] Cady A B, Delaney K J, Uetz G W. Contrasting energetic costs of courtship signaling in two wolf spiders having divergent courtship behaviors. Journal of Arachnology, 2011, 39(1): 161- 165.

[28] Kotiaho J S, Alatalo R V, Mappes J, Nielsen M G, Parri S, Rivero A. Energetic costs of size and sexual signalling in a wolf spider. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 1998, 265(1411): 2203- 2209.

[29] Kotiaho J S, Alatalo R V, Mappes J, Parri S. Sexual signalling and viability in a wolf spider (Hygrolycosarubrofasciata): measurements under laboratory and field conditions. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology, 1999, 46(2): 123- 128.

[30] Mappes J, Alatalo R V, Kotiaho J, Parri S. Viability costs of condition-dependent sexual male display in a drumming wolf spider. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Science, 1996, 263(1371): 785- 789.

[31] Shamble P S, Wilgers D J, Swoboda K A, Hebets E A. Courtship effort is a better predictor of mating success than ornamentation for male wolf spiders. Behavioral Ecology, 2009, 20(6): 1242- 1251.

[32] Ayyagari L R, Tietjen W J. Preliminary isolation of male-inhibitory pheromone of the spiderSchizocosaocreata(Araneae, Lycosidae). Journal of Chemical Ecology, 1987, 13(2): 237- 244.

[33] Arnqvist G. Comparative evidence for the evolution of genitalia by sexual selection. Nature, 1998, 393(6687): 784- 786.

[34] Jiao X G, Chen Z Q, Wu J, Du H Y, Liu F X, Chen J, Li D Q. Male remating and female fitness in the wolf spiderPardosaastrigera: the role of male mating history. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology, 2011, 65(2): 325- 332.

Effects of conspecific rivals on male courtship and mating in the monandrous wolf spiderPardosaastrigera

CHEN Bo1, WEN Lelei1, ZHAO Jupeng2, LIANG Honghe3, CHEN Jian1, JIAO Xiaoguo1,*

1CenterforBehavioralEcology&Evolution,HubeiCollaborativeInnovationCenterforGreenTransformationofBio-Resources,CollegeofLifeSciences,HubeiUniversity,Wuhan430062,China2GuangdongEntry-ExitInspectionandQuarantineTechnologyCenter,Guangzhou510623,China3SubtropicalCropsResearchInstituteofGuangxiZhuangAutonomousRegion,Nanning530002,China

Male sperm or semen production is costly across diverse taxa. Consequently, depending on mate quality and the competitive intensity of rivals, males are predicted to adaptively invest their courtship and mating efforts to maximize their reproductive success, while prudently allocating their sperm. Presently, most studies on male plastic behavioral responses to rivals have mainly focused on polyandrous females. Recent studies provide evidence that male plastic behavioral responses are plentiful and varied, found in a wide range of taxa, and comprise behaviors that occur pre- or post-copulation. It is predicted that males altered aspects of their mating behavior when indirectly exposed to rival chemical cues, and directly exposed to the sex ratio or the presence, number, or density of rivals. Generally, males exhibit adaptively behavioral responses to rival cues to maximize their reproductive fitness. In contrast, we have limited information about male behavioral responses to rival cues in monandrous species. In the present study, we used the monandrous wolf spider,Pardosaastrigera, as a model system to test male plastic behavioral responses to rival chemical cues and different operational sex ratios. It is generally accepted that in wandering spiders, males depend on female silk-mediated chemical substances to search and locate mates. Besides encountering the silk of females of different periods, such as immature and mature virgin females, and mated females, males may also encounter male silk and a mix of female and male silk. Given that males gain mating opportunities via pre-copulatory mate choice, it is predicted that males may invest more courtship intensity in the silk of virgin females than those of males and/or a mix of female and male silk. When maleP.astrigeraindividuals were exposed to the female silk previously occupied by themselves or other males, we compared the differences in male courtship latency, courtship duration, courtship intensity, and mating duration across mating treatments. Our results showed that male courtship intensity (foreleg raises per second and body shakes per second) was significantly reduced when they were exposed to female silk previously occupied by their own silk or by other males than female silk not previously occupied by males; however, there were no significant differences in male courtship latency, courtship duration, and mating duration. Although, when maleP.astrigeraindividuals were directly exposed to different operational sex ratios, our results indicated that varied sex ratios showed a small effect on male courtship and mating behaviors. The present study concurs with our prediction, which shows that maleP.astrigerapossessed pre-copulatory adaptive responses to rival chemical cues, but showed limited plastic behavioral responses to operational sex ratios. To our knowledge, this is the first study to determine male plastic behavioral responses to conspecific rivals in monandrous spiders.

Pardosaastrigera; single mating; courtship and mating; adaptive response; plastic behavior

國家自然科學基金資助項目(30800121)

2016- 04- 22; 網絡出版日期:2017- 02- 22

10.5846/stxb201604220754

*通訊作者Corresponding author.E-mail: jiaoxg@hubu.edu.cn

陳博,文樂雷,趙菊鵬,梁宏合,陳建,焦曉國.同種雄性競爭對手的存在對星豹蛛雄蛛求偶和交配行為的影響.生態學報,2017,37(11):3932- 3938.

Chen B, Wen L L, Zhao J P, Liang H H, Chen J, Jiao X G.Effects of conspecific rivals on male courtship and mating in the monandrous wolf spiderPardosaastrigera.Acta Ecologica Sinica,2017,37(11):3932- 3938.