環己烯對噻吩在CuY分子篩上吸附的影響機制

莫周勝 秦玉才 張曉彤 段林海 宋麗娟,,*

(1中國石油大學(華東)化學工程學院,山東 青島 266555;2遼寧石油化工大學,遼寧省石油化工催化科學與技術重點實驗室,遼寧 撫順 113001)

環己烯對噻吩在CuY分子篩上吸附的影響機制

莫周勝1秦玉才2張曉彤2段林海2宋麗娟1,2,*

(1中國石油大學(華東)化學工程學院,山東 青島 266555;2遼寧石油化工大學,遼寧省石油化工催化科學與技術重點實驗室,遼寧 撫順 113001)

利用液相離子交換法制備了CuY分子篩,并用X射線光電子能譜分析(XPS)對Cu元素進行了價態表征,用原位傅里葉轉換紅外(in-situ FTIR)和氨氣程序升溫脫附(NH3-TPD)技術對其進行了酸性表征。同時,以噻吩和環己烯為探針分子,CuY分子篩為吸附劑,研究了環己烯對噻吩在CuY分子篩B酸中心上吸附的影響機制。實驗結果顯示,CuY分子篩表層的Cu離子主要以Cu+為主,其表面酸性主要由中強B酸和L酸組成。與稀土離子不同的是,銅離子的存在抑制了噻吩或環己烯在B酸中心上的聚合反應。因此,環己烯主要通過與噻吩的競爭吸附影響噻吩在CuY分子篩B酸性位上的吸附。

原位傅里葉轉換紅外光譜;質子酸;競爭吸附;反協同效應

1 Introduction

Environmental concerns have driven people of nowadays to use fuel of very low sulfur content1. In recent years, governments worldwide have made increasingly stringent regulations to limit sulfur levels in fuels. European Union gasoline and diesel fuel specifications call for 10 mg·kg-1sulfur in Euro-IV2. In China, Beijing has been enforcing the national V standard since May 2012, requiring less than 10 mg·kg-1of sulfur content in automotive gasoline or diesel fuel3. A conventional process for removal of sulfur from liquid fuels is catalytic hydrodesulfurization (HDS). HDS of fluid catalytic cracking (FCC) gasoline is a straightforward way for reducing the sulfur to the levels even below 1 mg·kg-1. However, it needs high investment, operating costs and significant loss in the octane number caused by saturation of olefins4.

To produce ultra-clean fuels, new desulfurization approaches like selective adsorptive desulfurization (SADS) and oxidative desulfurization (ODS) are currently being explored as a valid supplement to HDS process1,5. Among these ways, SADS is regarded as one of the most appropriate and promising deep desulfurization methods because it does not only can be operated at relative low temperature and pressure, but also requires no hydrogen6. Various types of adsorbents for SADS, such as metal oxides, active carbon, clays, zeolites, mesoporous materials, composite zeolite and so on, have been reported for the adsorptive removal of sulfur compounds in fuels7-13. Metal ion modified Y zeolites have been explored as effective adsorbents due to their high ion-exchange capacity, sizeselective adsorption capacity and their thermal and mechanical stabilities14.

Yang and coworkers15-17reported that CuY, AgY and NiY zeolites were effective for the removal of thiophenic compounds which were the major sulfur compounds in fuels by providing a π-complexation between thiophenic compounds and the transition metal cations (Lewis acidity, or L acidity) loaded on the zeolites. But when aromatics and olefins coexist with thiophenic compounds in transportation fuels, the capacities of the zeolites for adsorption desulfurization drop sharply18-20. Influencing mechanism of aromatics on adsorption of thiophenic compounds is often attributed to the competitive adsorptions between aromatics and thiophenic compounds on CuY zeolite. But as far as we know, influencing mechanism of olefins has not been reported.

Song and coworkers21studied Cu2+Y, Ni2+Y, and Ce4+Y for the removal of sulfur compounds from commercial aviation fuels and the result showed that Ce4+Y has higher selectivity than the other metal-exchanged zeolites via direct sulfur atom and metal ion interaction (S-M interaction). Tian et al.22also proved that introduction of Ce4+ion to NaY zeolites weakens the effect of competitive adsorption between thiophene and toluene, but can not be eliminated completely. In addition, adsorption of thiophenic compounds over CeY zeolite can be strongly affected by the olefins via competitive adsorption23,24. Besides the competitive adsorption, Br?nsted acidity (B acidity) of Y zeolites is another important hindering factor for the desulfurization performance of CeY. This is because adsorption of thiophene over B acid sites of HY zeolites will lead to further oligomerization phenomena25,26. Meanwhile, the olefins in the fuels also can oligomerize with itself and alkylate thiophene under catalysis of B acidity26,27. These reactions not only inhibit further adsorption of thiophenic compounds onto adsorbent, but also make the regeneration of adsorbent become more difficult28. Our previous studies also confirmed that competitive adsorptions between aromatics, olefins and thiophenic compounds and B acid catalysis are two crucial factors in sulfur removal10,11,23,29-33.

It is noteworthy that influencing mechanism of olefins on LaY or CeY is competitive adsorption (on L acid site) and B acid catalysis (on B acid site), but the influencing mechanism of olefins for CuY or AgY is still unknown. It is beneficial to develop and design new type Cu-based adsorbents with good sulfur selectivity and high sulphur capacity for real fuel oil which contains aromatics and olefins by solving this question. For example, the improvement of bimetal ion-exchanged zeolite19,20. Therefore, this main aim of paper is to reveal the influencing mechanism of olefins on adsorption of thiophenic compounds over CuY zeolite by in-situ Fourier transform infrared (in-situ FTIR) spectroscopy. In-situ FTIR spectroscopy is effective mean for investigating the absorption mechanism of small organic molecule (e.g. thiophene and dimethyl disulfide) on zeolites6,27,29,33.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Adsorbent preparation

NaY zeolite (the molar ratio of Si and Al is 2.55, Nankai University catalyst Co., Ltd.) in powder form was used as the starting material. The CuY zeolite was prepared by liquid phase ion exchange (LPIE) method29in which NaY zeolite was treated with 0.1 mol·L-1Cu(NO3)2aqueous solution at boiling condition for 4 h. In order to obtain the CuY with higher copper ion loading, the ion exchanged experiment was repeated. Finally, the CuY zeolite was calcined at 500 °C for 6 h under a flowing nitrogen atmosphere for improving Cu+/Cu2+ratio of CuY zeolite because Cu+is needed for π-complexation during the adsorption of sulfur with CuY34.

2.2 Characterization of adsorbent

X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) analyse was conducted on a Thermo ESCALAB 250 spectrometer equipped with an Al KαX-ray source (hν = 1486.6 eV). The typical base pressure was 5.0×10-7Pa. The binding energies were calibrated by referencing the C 1s peak (284.6 eV) to reduce the sample charge effect.

The acidity was monitored by pyridine in-situ FTIR (Py-FTIR) technique, with a Perkin-Elmer Spectrum TM GX spectrometer (Perkin-Elmer, USA) coupled to a conventional high vacuum system. NH3-TPD experiments were performedon a Micromeritics Auto Chem II Chemisorption Analyzer (Micromeritics, USA) with a thermal conductivity detector. The sample was treated in He gas flow at 500 °C for 1 h.

2.3 Adsorption experiments

The CuY zeolites were pressed into thin wafers (12-15 mg·cm-2) and activated at 400 °C under vacuum (10-3Pa) for 4 h. The wafers were respectively exposed to the vapors of thiophene, cyclohexene, and the co-adsorption vapors of thiophene and cyclohexene at room temperature (RT) and evacuated 30 min at 100, 200, 300 or 400 °C, then recorded the IR spectra after cooling to room temperature at each desorption temperature. IR spectra were recorded using a Perkin-Elmer Spectrum TM GX spectrometer. An in-situ IR cell coupled to a conventional high vacuum system was utilized allowing the sample wafers can be heated under vacuum or exposed to vapor-phase probe molecules.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 XPS Analysis

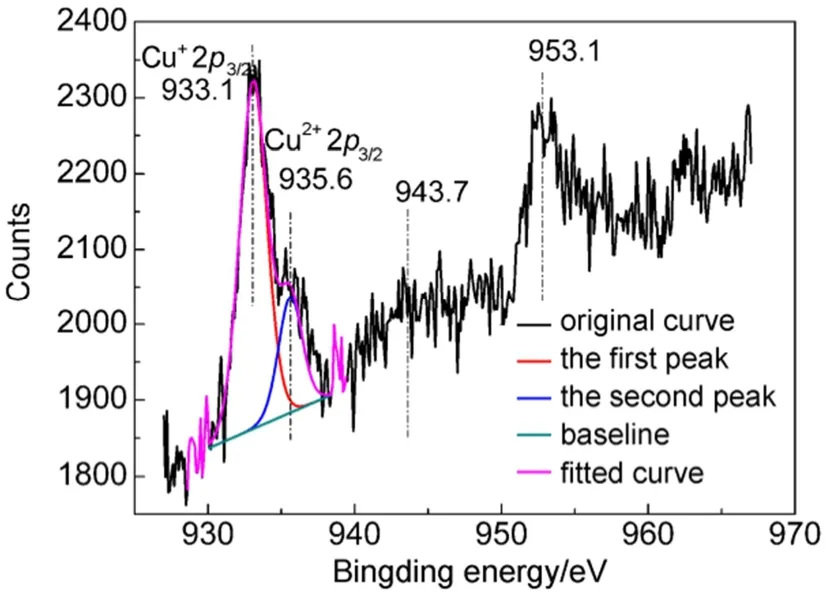

Fig.1 shows chemical state of Cu in CuY zeolite. In the XPS spectrum of CuY zeolite, the peaks of binding energies at 933.1 and 935.6 eV correspond to Cu+2p3/2and Cu2+2p3/2, respectively. The peaks at 953 and 943.7 eV correspond to Cu 2p1/2and satellite of Cu2+2p3/2, respectively34,35. The two peaks at 933.1 and 935.6 eV were fitted and their peak areas were calculated by the XPS peak software for obtaining the relative content ratio of Cu+/Cu2+. The calculated result demonstrates that peak area ratio of 933.1 and 935.6 eV is 1 : 0.29, which means that the content of Cu+on the surface of CuY zeolite is larger than Cu2+. Indeed, the concentration of Cu+in CuY zeolite prepared LPIE method is high36and is helpful to improve the selective adsorption desulfurization performance of CuY zeolite.

3.2 Characterization of the surface acidity

Fig.1 XPS spectra of Cu ion in CuY zeolite

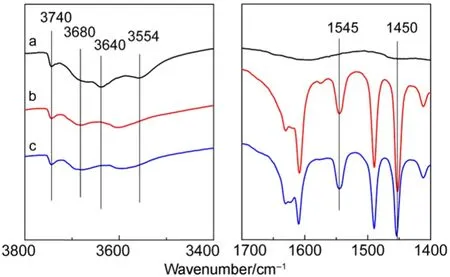

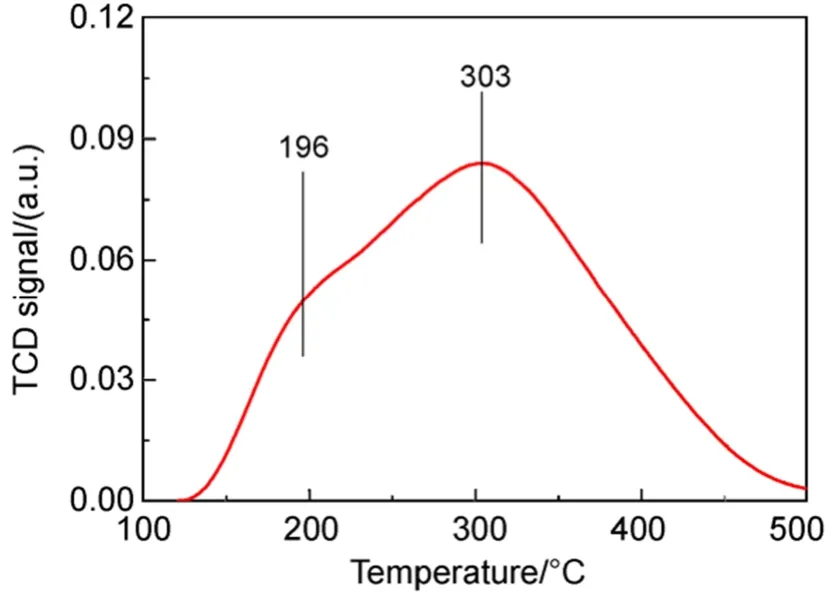

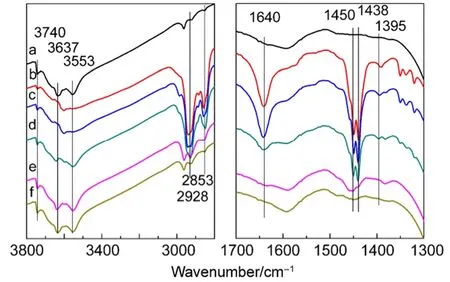

As shown in Fig.2a, CuY zeolite exhibits four hydroxyl bands attributed to: (I) SiOH groups terminating the crystal structure (3742 cm-1), (II) AlOH groups (3680 cm-1), (III) OH groups in the supercage (3640 cm-1) and (IV) OH groups in the sodalite cage (3554 cm-1)37,38. When pyridine was adsorbed (Fig.2b), hydroxyl bands at 3640 and 3554 cm-1disappeared and new absorption bands 1544 and 1450 cm-1appeared. Adsorption band at 1545 cm-l, due to pyridinium ions, is indicative of B acidity while absorption band at 1450 cm-l, due to coordinately bound pyridine with cations (Al3+or Cu+/Cu2+for CuY zeolite), is characteristic of L acidity38,39. With desorption temperature increasing, small amount of hydroxyl bands were recovered (Fig.2c). It means that the acid strength of partial hydroxyls is weak. Combined with the result of NH3-TPD showed in Fig.3, it can be found that the acidity of CuY zeolite is mainly medium and strong B acid and L acid.

3.3 Single-component adsorption

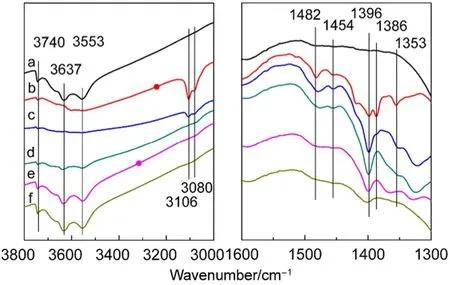

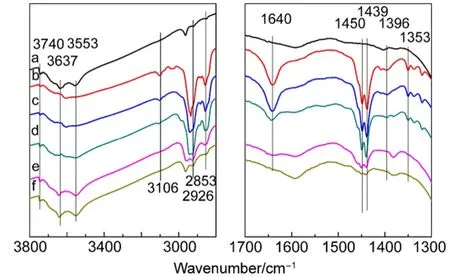

The in situ FTIR spectrograms of thiophene and cyclohexene adsorbed on CuY are given in Fig.4 and Fig.5, respectively. The band at 3106 and 1396 cm-1can be ascribed to the ν(=C―H) and vsym(C=C) of thiophene adsorbed on L acid or B acid via π-electronic interaction, respectively31,40. They also exist in FTIR spectrograms of thiophene adsorbed on NaY, HY or CeY29. 1482, 1386 and 1353 cm-1only appear in CuY and are absent in NaY, HY or CeY. 1386 cm-1come from v(C=C) of thiophene adsorbed on CuY zeolite by physisorption. 1454 and 1353 cm-1may result from thiophene connected with Cu2+or Cu+by S-M (S-Cu) bond, while 1482 cm-1can be ascribed to thiophene adsorbed on Cu+by π-complexation41,42. Unlike the FTIR spectrogram of thiophene adsorbed on CeY zeolite, the FTIR spectrogram of thiophene adsorbed on CuY zeolite have not the bands 1504 and 1439 cm-1which are an indicationof thiophene polymerization on B acid site. It means thiophene adsorbed on the B acid site or L acid site does not generate further acid catalytic reaction. The hydroxyl bands at 3740, 3637 and 3553 cm-1recover gradually, while 3106 and 1500-1300 cm-1slowly disappear as the temperature rises. This indicates that thiophene gradual desorbs when temperature increases. However, thiophene is not removed completely due to the existence of strong B and L acid sites.

Fig.2 Py-FTIR spectra of CuY zeolite

Fig.3 NH3-TPD spectra of CuY zeolite

Fig.4 FTIR spectra of thiophene adsorbed on CuY zeolite

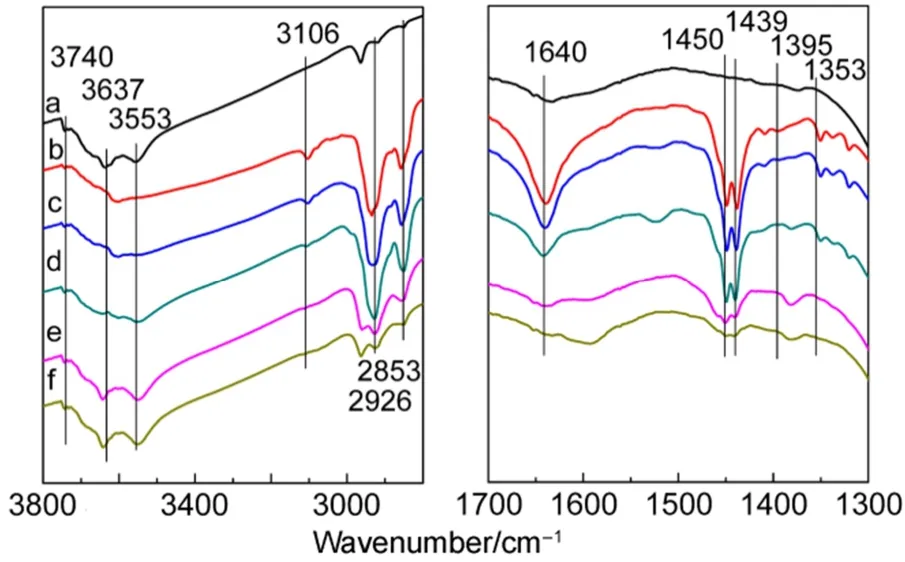

Fig.5 FTIR spectra of cyclohexene adsorbed on CuY zeolite

The FTIR spectra of cyclohexene adsorbed on CuY and then desorbed at higher temperatures is shown in Fig.5. The bands 2928 and 2853 cm-1corresponding to vasymand vsymof ―CH2―of cyclohexene, respectively. The 1640 cm-1assigned to ν(C=C) of cyclohexene shifts to lower frequencies compared with those of gaseous cyclohexene 1653 cm-1. This implies the interaction of C=C bond of cyclohexene with B acid or L acid is π-complex27,33. 1450 and 1438 cm-1are respectively the characteristic peaks of δasymof methylene ―CH2― and =CH―CH2― of cyclohexene. The absence of 1520 cm-1which has been attributed to the sign of formation of alkenyl carbenium ions27,29indicates adsorbed cyclohexene did not generate oligomerization. The ratio of intensities of the 1450 cm-1band and the 1438 cm-1band greatly increases at 300 °C (Fig.5e). This implies some =CH―CH2― bands transform into ―CH2―CH2― by the protonation of cyclohexene and coke with the increase of temperature43. The reaction of cyclohexene on CuY zeolite is different from on HY, LaY or CeY zeolites. Protonation and oligomerization of cyclohexene easily occur on HY, LaY or CeY even at room temperature27,29.

3.4 Bi-component adsorption

The FTIR spectrograms of co-adsorption of thiophene and cyclohexene on CuY are shown in Fig.6 and Fig.7. Thiophene was first adsorbed and then cyclohexene in Fig.6, and cyclohexene was first adsorbed and then thiophene in Fig.7. The apparent bands at 1450 and 1439 cm-1in Fig.6 mean adsorption of cyclohexene is obvious when thiophene is adsorbed at first, but the weak bands at 3106 and 1396 cm-1mean adsorption of thiophene is weakened. Therefore, the competitive adsorption between thiophene and cyclohexene is strong.

When cyclohexene is adsorbed at first (see Fig.7), adsorption of thiophene is weak because the intensities of band 1396 cm-1is weak. Meanwhile, the intensities of bands at 1450 and 1439 cm-1are weaker than in Fig.5. The phenomena also indicate the existence of competitive adsorption between cyclohexene and thiophene. Similarly, the absence of 1520 cm-1indicates oligomerization of cyclohexene did not take place29. The resultis in agreement with the results of adsorption desulfurization experiments18,20that the addition of olefins in model gasolines containing thiophenic sulfides resulted in significantly reduce of adsorption desulfurization performance of CuY zeolite.

Fig.6 FTIR spectra of thiophene and cyclohexene adsorbed on CuY zeolite

Fig.7 FTIR spectra of cyclohexene and thiophene adsorbed on CuY zeolite

4 Conclusions

From the results obtained in this study, it can be found that acidity of CuY zeolite is composed by medium and strong B acidity and L acidity. The B acidity did not lead to polymerization reaction of thiophene or cyclohexene on CuY, although the polymerization reaction can occur easily on HY or REY. The reason may be that existence of copper ion (L acidity) inhibits the proceeding of intermolecular polymerization reaction of thiophene or cyclohexene over B acid sites. Besides, cyclohexene has a negative effect to thiophene adsorption over B or L acid sites of CuY by competitive adsorption. Thus, influencing mechanism of cyclohexene on thiophene adsorption over CuY is competitive adsorption rather than catalysis of B acidity. How to avoid the competitive adsorption of olefins and thiophenic compounds is still a development direction of improvement of adsorbent for adsorption desulfurization. Furthermore, the discovery of anti-synergistic effect between B acidity and copper ion in Y zeolite is helpful for understanding catalytic property of CuY zeolite.

(1) Saha, B.; Sengupta, S. Fuel 2015, 150, 679. doi: 10.1016/j.fuel.2015.02.078

(2) Dasgupta, S.; Agnihotri, V.; Gupta, P.; Nanoti, A.; Garg, M. O.; Goswami, A. N. Catal. Today 2009, 141, 84. doi: 10.1016/j.cattod.2008.04.005

(3) Li, D. D. Chin. J. Catal. 2013, 34, 48. [李大東. 催化學報, 2013, 34, 48.] doi: 10.1016/S1872-2067(11)60508-1

(4) Mortaheb, H. R.; Ghaemmaghami, F.; Mokhtarani, B. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2012, 90, 409. doi: 10.1016/j.cherd.2011.07.019

(5) Sitamraju, S.; Xiao, J.; Janik, M. J.; Song, C. S. J. Phys. Chem. C 2015, 119, 5903. doi: 10.1021/jp510326h

(6) Lv, L.; Zhang, J.; Huang, C.; Lei, Z.; Chen, B. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2014, 125, 247. doi: 10.1016/j.seppur.2014.02.002

(7) Xiao, J.; Li, Z.; Liu, B.; Xia, Q.; Yu, M. Energy Fuels 2008, 22, 3858. doi: 10.1021/ef800437e

(8) Hernández-Maldonado, A. J.; Qi, G.; Yang, R. T. Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 2005, 61, 212. doi: 10.1016/j.apcatb.2005.05.003

(9) Wang, Y.; Yang, R. T.; Heinzel, J. M. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2008, 63, 356. doi: 10.1016/j.ces.2007.09.002

(10) Shao, X. C.; Zhang, X. T.; Yu, W. G.; Wu, Y. Y.; Qin, Y. C.; Sun, Z. L.; Song, L. J. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2012, 263, 1. doi: 10.1016/j.apsusc.2012.07.142

(11) Shao, X. C.; Duan, L. H.; Wu, Y. Y.; Qin, Y. C.; Yu, W. G.; Wang, Y.; Li, H. L.; Sun, Z. L.; Song, L. J. Acta Phys. -Chim. Sin. 2012, 28, 1467. [邵新超, 段林海, 武玉葉, 秦玉才, 于文廣, 王 源, 李懷雷, 孫兆林, 宋麗娟. 物理化學學報, 2012, 28, 1467.] doi: 10.3866/PKU.WHXB201203312

(12) Sui, P. P.; Meng, X. H.; Wu, Y. Y.; Zhao, Y. Y.; Song, L. J.; Sun, Z. L.; Duan, L. H.; Umar, A.; Wang, Q. Sci. Adv. Mater. 2013, 5, 1132. doi: 10.1166/sam.2013.1564

(13) Sun, H. Y.; Sun, L. P.; Li, F.; Zhang, L. Fuel Process. Technol. 2015, 134, 284. doi: 10.1016/j.fuproc.2015.02.010

(14) Montazerolghaem, M.; Seyedeyn-Azad, F.; Rahimi, A. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 2014, 32, 328. doi: 10.1007/s11814-014-0213-1

(15) Yang, R. T.; Hernández-Maldonado, A. J.; Yang, F. H. Science 2003, 301, 79. doi: 10.1126/science.1085088

(16) Hernández-Maldonado, A. J.; Yang, R. T. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2003, 42, 123. doi: 10.1021/ie020728j

(17) Hernández-Maldonado, A. J.; Yang, F. H.; Qi, G.; Yang, R. T. Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 2005, 56, 111. doi: 10.1016/j.apcatb.2004.06.023

(18) King, D. L.; Li, L. Catal. Today 2006, 116, 526. doi: 10.1016/j.cattod.2006.06.026

(19) Song, H.; Cui, X. H.; Song, H. L.; Gao, H. J.; Li, F. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2014, 53, 14552. doi: 10.1021/ie404362f

(20) Song, H.; Wan, X.; Dai, M.; Zhang, J.; Li, F.; Song, H. Fuel Process. Technol. 2013, 116, 52. doi: 10.1016/j.fuproc.2013.04.017

(21) Velu, S.; Ma, X. L.; Song, C. S. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2003, 42, 5293. doi: 10.1021/ie020995p

(22) Shi, Y. C.; Yang, X. J.; Tian, F. P.; Jia, C. Y.; Chen, Y. Y. J. Nat. Gas Chem. 2012, 21, 421. [石艷春, 楊瀟健, 田福平, 賈翠英, 陳永英.天然氣化學, 2012, 21, 421.] doi: 10.1016/S1003-9953(11)60385-X

(23) Wang, H. G.; Song, L. J.; Jiang, H.; Xu, J.; Jin, L. L.; Zhang, X. T.; Sun, Z. L. Fuel Process. Technol. 2009, 90, 835. doi: 10.1016/j.fuproc.2009.03.004

(24) Liao, J. J.; Bao, W. R.; Chang, L. P. Fuel Process. Technol. 2015, 140, 104. doi: 10.1016/j.fuproc.2015.08.036

(25) Geobaldo, F.; Palomino, G. T.; Bordiga, S.; Zecchina, A.; Areán, C. O. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 1999, 1, 561. doi: 10.1039/A807353H

(26) Richardeau, D.; Joly, G.; Canaff, C.; Magnoux, P.; Guisnet, M.; Thomas, M.; Nicolaos, A. Appl. Catal. A: Gen. 2004, 263, 49. doi: 10.1016/j.apcata.2003.11.039

(27) Shi, Y. C.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, H. X.; Tian, F. P.; Jia, C. Y.; Chen, Y. Y. Fuel Process. Technol. 2013, 110, 24. doi: 10.1016/j.fuproc.2013.01.008

(28) Laborde-Boutet, C.; Joly, G.; Nicolaos, A.; Thomas, M.; Magnoux, P. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2006, 45, 6758. doi: 10.1021/ie060168e

(29) Qin, Y. C.; Mo, Z. S.; Yu, W. G.; Dong, S. W.; Duan, L. H.; Gao, X. H.; Song, L. J. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2014, 292, 5. doi: 10.1016/j.apsusc.2013.11.036

(30) Qin, Y. C.; Gao, X. H.; Pei, T. T.; Zheng, L. G.; Wang, L.; Mo, Z. S.; Song, L. J. J. Fuel Chem. Technol. 2013, 41, 889. [秦玉才, 高雄厚,裴婷婷, 鄭蘭歌, 王 琳, 莫周勝, 宋麗娟. 燃料化學學報, 2013, 41, 889.]

(31) Qin, Y. C.; Gao, X. H.; Duan, L. H.; Fan, Y. C.; Yu, W. G.; Zhang, H. T.; Song, L. J. Acta Phys. -Chim. Sin. 2014, 30, 544. [秦玉才, 高雄厚,段林海, 范躍超, 于文廣, 張海濤, 宋麗娟. 物理化學學報, 2014, 30, 544.] doi: 10.3866/PKU.WHXB201401021

(32) Zhang, C.; Qin Y. C.; Gao X. H.; Zhang H. T.; Mo Z. S.; Chu C. Y.; Zhang, X. T.; Song, L. J. Acta Phys. -Chim. Sin. 2015, 31, 344. [張暢, 秦玉才, 高雄厚, 張海濤, 莫周勝, 初春雨, 張曉彤, 宋麗娟.物理化學學報. 2015, 31, 344.] doi: 10.3866/PKU.WHXB201412163

(33) Zhang, X. T.; Yu, W. G.; Qin, Y. C.; Dong, S. W.; Pei, T. T.; Wang, L. T.; Song, L. J. Acta Phys-chim. Sin. 2013, 29, 1273. [張曉彤, 于文廣,秦玉才, 董世偉, 裴婷婷, 王陵濤, 宋麗娟. 物理化學學報, 2013, 29, 1273.] doi: 10.3866/PKU.WHXB201303183

(34) Shan, J. H.; Liu, X. Q.; Sun, L. B.; Cui, R. Energy Fuels 2008, 22, 3955. doi: 10.1021/ef800296n

(35) Richtera, M.; Fait, M. J. G.; Eckelt, R.; Schneider, M.; Radnik, J.; Heidemann, D.; Fricke, R. J. Catal. 2007, 245, 11. doi: 10.1016/j.jcat.2006.09.009

(36) Li, Z.; Fu, T. J.; Zheng, H. Y. Chin. J. Inorg. Chem. 2011, 27, 1483. [李 忠, 付廷俊, 鄭華艷. 無機化學學報, 2011, 27, 1483.]

(38) Benaliouche, F.; Boucheffa, Y.; Ayrault, P.; Mignard, S.; Magnoux, P. Micropor. Mesopor. Mat. 2008, 111, 80. doi: 10.1016/j.micromeso.2007.07.006

(39) Ward, J. W. J. Catal. 1971, 22, 237. doi: 10.1016/0021-9517(71)90190-4

(40) Garcia, C. L.; Lercher, J. A. J. Phys. Chem. 1992, 96, 2669. doi: 10.1021/j100185a050

(41) Tang, X. L.; Shi, L. Langmuir. 2011, 27, 11999. doi: 10.1021/la2025654

(42) Mills, P.; Korlann, S.; Bussell, M. E.; Reynolds, M. A.; Ovchinnikov, M. V.; Angelici, R. J.; Stinner, C.; Weber, T.; Prins, R. J. Phys. Chem. A 2001, 105, 4418. doi: 10.1021/jp010258r

(43) Jolly, S.; Saussey, J.; Lavahey, J. C. J. Mol. Catal. 1994, 86, 401. doi: 10.1016/0304-5102(93)E0156-B

Influencing Mechanism of Cyclohexene on Thiophene Adsorption over CuY Zeolites

MO Zhou-Sheng1QIN Yu-Cai2ZHANG Xiao-Tong2DUAN Lin-Hai2SONG Li-Juan1,2,*

(1College of Chemistry & Chemical Engineering, China University of Petroleum (East China), Qingdao 266555, Shandong Province, P. R. China;2Key Laboratory of Petrochemical Catalytic Science and Technology of Liaoning Province, Liaoning Shihua University, Fushun 113001, Liaoning Province, P. R. China)

A CuY zeolite prepared by liquid phase ion exchange was characterized by X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy, pyridine in situ Fourier transform infrared (in situ FTIR) spectroscopy, and ammonia temperature programmed desorption. The effect of cyclohexene on the adsorption of thiophene over the prepared CuY zeolite was explored by in situ FTIR. In particular, the role of the zeolite’s Br?nsted acidity was investigated in the adsorption process. The results show that the percentage of Cu+on the surface of the CuY zeolite can reach 77%. The surface acidity of the CuY zeolite mainly comprises medium and strong Br?nsted acidity and Lewis acidity. According to the adsorption results, cyclohexene negatively influences thiophene adsorption on the Br?nsted or Lewis acid sites in CuY by competitive adsorption. Although polymerization of thiophene and cyclohexene can occur easily on the HY or REY zeolites, the presence of Br?nsted acids in the CuY zeolite was not sufficient to polymerize either thiophene or cyclohexene. This difference may be caused by an anti-synergistic effect between the Cu ions of the CuY zeolite and neighboring Br?nsted acid sites, the result of which inhibits the polymerization of adsorbed thiophene and cyclohexene.

In-situ FTIR spectroscopy; Br?nsted acidity; Competitive adsorption; Anti-synergistic effect

November 25, 2016; Revised: March 10, 2017; Published online: March 28, 2017.

O643

Ward, J. W. J. Catal. 1967, 9, 225.

10.1016/0021-9517(67)90248-5

doi: 10.3866/PKU.WHXB201703281

*Corresponding author. Email: lsong56@263.net; Tel: +86-024-56860658.

The project was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (21376114, 21476101) and Major Program of Petroleum Refining of Catalyst of PetroChina Company Limited (10-01A-01-01-01).

國家自然科學基金(21376114, 21476101)和中國石油天然氣股份有限公司煉油催化劑重大專項(10-01A-01-01-01)資助項目

? Editorial office of Acta Physico-Chimica Sinica