Effects of a general practitioner cooperative co-located with an emergency department on patient throughput

Michiel J. van Veelen, Crispijn L. van den Brand, Resi Reijnen, M. Christien van der Linden

1Department of Emergency Medicine, University of Botswana, School of Medicine, Gaborone, Botswana

2Department of Emergency Medicine, Medical Center Haaglanden, The Hague, The Netherlands

Corresponding Author: M. Christien van der Linden, Email: c.van.der.linden@mchaaglanden.nl

Effects of a general practitioner cooperative co-located with an emergency department on patient throughput

Michiel J. van Veelen1, Crispijn L. van den Brand2, Resi Reijnen2, M. Christien van der Linden2

1Department of Emergency Medicine, University of Botswana, School of Medicine, Gaborone, Botswana

2Department of Emergency Medicine, Medical Center Haaglanden, The Hague, The Netherlands

Corresponding Author: M. Christien van der Linden, Email: c.van.der.linden@mchaaglanden.nl

BACKGROUND: In 2013 a General Practitioner Cooperative (GPC) was introduced at the Emergency Department (ED) of our hospital. One of the aims of this co-located GPC was to improve throughput of the remaining patients at the ED. To determine the change in patient fl ow, we assessed the number of self-referrals, redirection of self-referrals to the GPC and back to the ED, as well as ward and ICU admission rates and length of stay of the remaining ED population.

METHODS: We conducted a four months' pre-post comparison before and after the implementation of a co-located GPC with an urban ED in the Netherlands.

RESULTS: More than half of our ED patients were self-referrals. At triage, 54.5% of these selfreferrals were redirected to the GPC. After assessment at the GPC, 8.5% of them were referred back to the ED. The number of patients treated at the ED declined with 20.3% after the introduction of the GPC. In the remaining ED population, there was a signifi cant increase of highly urgent patients (P<0.001), regular admissions (P<0.001), and ICU admissions (P<0.001). Despite the decline of the number of patients at the ED, the total length of stay of patients treated at the ED increased from 14 682 hours in the two months' control period to 14 962 hours in the two months' intervention period, a total increase of 270 hours in two months (P<0.001).

CONCLUSION: Introduction of a GPC led to effi cient redirection of self-referrals but failed to improve throughput of the remaining patients at the ED.

Emergency Service, hospital; General practitioners; Crowding; Length of stay

World J Emerg Med 2016;7(4):270–273

INTRODUCTION

Emergency department (ED) crowding is an increasingly recognised problem that affects hospitals all over the world.[1,2]Causes for ED crowding include input causes (such as the increase in ED presentations),[3]throughput causes (such as waiting times for diagnostics), and output factors (such as lack of inpatient capacity).[4]While output factors are considered to be the most important cause of ED crowding[5]e.g. waiting for an inpatient bed,[6]the growing number of visits by so called self-referrals with minor problems who could be seen by a general practitioner (GP) is also of concern for EDs.[7,8]The organization of out-of-hour services in primary care has changed, with new models such as large GP cooperatives (GPCs) and primary care centres integrated into EDs.[9–11]

In the Netherlands, the proportion of self-referrals at EDs is approximately 30%.[12]Almost all Dutch citizens have a GP and basic health insurance. GPs are obliged to organise a 24-hour care system of availability, in which both regular and acute care is provided during offi ce hours and only acute care after hours. Some patients bypass their GP and present to the ED directly.[13]Reasons for selfreferrals for bypassing their GP are, amongst many other reasons, the EDs' easy access and the perceived need for hospital emergency care, e.g. the need for an X-ray.[13]To prevent patients from self-referring to the ED, GPs in the Netherlands have reorganised out-of-hours primary care from small practices into large GPCs co-located with EDs. In the study setting, a GPC was introduced in February 2013.

This paper describes what happened after the introduction of the GPC. It was assumed that the number of patients at the ED would decline when self-referrals with minor problems would be guided to the GPC. At the same time, there were concerns that time- and money consuming double consults would occur for a part of the self-referrals. Furthermore, it was assumed that redirecting a part of the patients to the GPC would have a positive impact on throughput times of the remaining patients at the ED.

The objectives of this study were to answer the following questions: (1) How many self-referrals are redirected from the ED to the GPC? (2) How many of these self-referrals are referred back to the ED after treatment at the GPC? (3) Are there signs of improved throughput of the remaining ED patient population?

METHODS

Design

A pre-post comparison before and after the implementation of a co-located GPC with an innercity, level one trauma centre in the Netherlands with approximately 52 000 patient visits annually. The answers to questions one and two were calculated during the intervention period (October and November 2013). For the answer to question three, total length of stay (LOS), patients' acuity level and admission rate) of the ED patients were compared between the intervention period (October and November 2013) and a control period (October and November 2012).

The regional medical research ethics committee and the institutional review board approved the study. The data set contained no individual identifiers to maintain anonymity of subjects.

Procedures and data collection

The ED uses the Manchester Triage System (MTS), a fi ve-point scale, to assess acuity level.[14]An extension in the MTS helps the triage nurse to identify patients eligible for treatment at the GPC. This extension was a consensus-based effort of GPs and hospital based specialists and triage nurses.

Data were retrieved from the hospitals' electronic patient database (ChipSoft, Amsterdam, the Netherlands). Data collected included demographic details (gender, age), arrival time, type of complaint, acuity level, discharge time, and disposition. Patients' LOS was defined as the interval between patients' arrival and the moment the patient left the ED.

Analysis

Descriptive analyses were conducted to describe patients' characteristics. Differences between the period before (control period) and period after (intervention period) the GPC implementation were analysed using χ2-tests (gender, age groups, acuity level, and disposition) and the Mann-Whitney U-tests (LOS). A P<0.05 was considered statistically significant. Data analysis was performed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS, version 22, Chicago, Illinois, USA).

RESULTS

During the two-month intervention period, 8 311 patients were registered at the ED. More than half of these patients were self-referred (4 372, 52.6%).

At triage, 1 989 (45.5%) of the self-referrals were redirected to the GPC. The remaining self-referrals (2 383, 54.5% of the self-referrals) were triaged to the ED.

Of all patients who were redirected to the GPC at triage, 169 (8.5%) patients needed specialist emergency care and were referred to the ED. These were mainly patients with limb problems with suspected bone fracture, and patients with abdominal complaints and an elevated CRP.

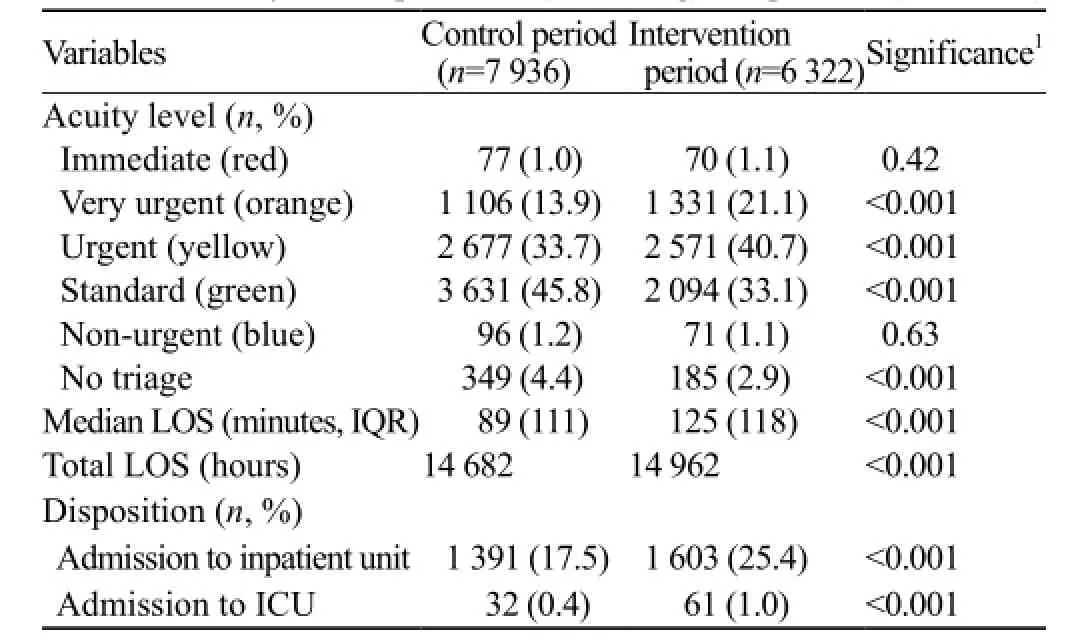

The number of patients treated at the ED declined with 20.3% compared to the control period (control period: 7 936 patients vs. 6 322 patients in the intervention period (Table 1). At the same time, there was a signifi cant increase in referred patients during the interventionperiod (2 963, 37.3%) in 2012 vs. 3 939 (47.4%) in 2013 within all categories of referred patients (ambulance, referred by GP, referred by medical specialists) (Table 1). Patients' median LOS increased significantly (control period 89 minutes vs. 125 minutes in the intervention period, P<0.001). The total LOS of all patients treated at the ED increased from 14 682 hours to 14 962 hours (a total increase of 270 hours, P<0.001), despite the fact that there were 1 614 patients less.

Table 1. GPC and ED patients during study period (n=16 247)

There was also a signifi cant increase of highly urgent patients (MTS acuity 2) [control period: 1 106 (13.9%) patients vs. intervention period: 1 331 (21.1%) patients] (Table 2). The number of regular admissions increased from 1 359 (17.5%) admissions in the control period to 1 603 (25.4%) admissions in the intervention period. The number of patients admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) almost doubled from 32 (0.4%) to 61 (1.0%).

Table 2. Severity of complaints of (remaining) ED patients (n=14 258)

DISCUSSION

This study carried out with a before and after intervention design showed that almost half of our ED patients were self-referrals, and of those selfreferrals, more than half were redirected to the GPC. The introduction of the co-located GPC with our ED resulted into a 20% reduction of ED patients. Despite the decline of the number of patients at the ED, there was no improved throughput of the remaining patients at the ED.

The self-referral rate at this urban hospital ED was 52.6%. This is high compared to the median percentage in the Netherlands, which is 30%.[12]This discrepancy might be explained by differences between hospitals in the population health status, and differences in the organization of the GP-services. Also, patients living in highly urbanised areas more commonly bypass their GPs.[12]

Self-referrals are believed to present with minor problems that should be treated by their GP. However, in our study only half of the self-referrals were redirected to the GPC. This may be partly due to the triage-methodology, partly to the GPs' lack of access to radiography, EKG and blood tests, and partly to the fact that some self-referrals have urgent problems.[13]

Only 8.5% of self-referrals directed to the GPC were referred back to the ED because they needed hospital emergency care. This low percentage probably does not justify the concerns for time- and money-consuming double consults. A prospective cost-effectiveness study is needed to confirm this. On the other hand, when considering the implementation of a GPC co-located with an ED, there is little evidence to support overall cost-effectiveness. Although marginal savings per patient may be realized, this is likely to be overshadowed by the overall cost of introducing a new service.[15]

In some other studies, the introduction of a co-located GPC with an ED has failed to reduce attendances.[15,16]Our study contradicts these fi ndings: 20% of our patients were referred to the GPC. Unfortunately, there were no signs of an improved throughput for the remaining patients at the ED. The latter is supported by other studies, the evidence for improved throughput when co-locating GPCs at EDs is poor.[15,17]

As said, the number of patients assessed and treated at the ED decreased with 20%. At the same time, the caseload at the ED changed significantly. More referred patients by GPs, by ambulances, and by medical specialists, an increase in acuity levels, and a higher admission rate indicate a significant change in the workload of this ED. These findings coincide with a previous study.[9]Obviously, more complex patients lead to increased LOSs, more inpatient admissions, and less inpatient capacity, which in turn cause increased workload and ED crowding.[5]A future study objectifying the effects of a co-located GPC with the ED would be of interest.

Limitations

In this study, we found that self-referrals were adequately triaged to the GPC and reduced patient volume. We also found an increase in the number of referred patients requiring more attention. Because of our pre- post design, we cannot prove a relationship between the two findings. In general, referred patients are more urgent and have higher admission rates as compared toself-referred patients.[13]Although the increase in ED patients who were referred by a GP seems associated with the location of the GPC at the ED, it is hard to prove causality since unknown external factors could play a role. Thus, the finding that the caseload at the ED changed significantly after the implementation of the GPC should be considered with great caution and warrants further research.

Second, we worked with computerised data. Data entry inaccuracies in the system could have biased the results. However, it is unlikely that inaccuracies were unequally divided over the different periods investigated.

Finally, this study conveys the experience of a single hospital and may have limited generalizability because of the characteristics of our population and differences in health care delivery. Nonetheless, we hope that our study can contribute towards a growing body of research that aims to understand the impact of introducing a colocated GPC with an ED.

In summary, our study adds further evidence that the implementation of a GPC can contribute to the delivery of effi cient health care for a part of the self-referrals at an ED. However, despite a 20% decrease in total number of patients, LOS of remaining patients at the ED increased, probably due to a change in patient population. The ED caseload changed, with more referred, complex patients while having less patient visits in total.

Funding: None.

Ethical approval: The regional medical research ethics committee and the institutional review board approved the study.

Confl icts of interest: All authors declare that they have no confl ict of interest.

Contributors: MJV had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. MJV, CLB, RR and MCL contributed to the study concept and design. MCL acquired the data. MJV and MCL analysed and interpreted the data. MJV and MCL drafted the manuscript. MJV, CLB, RR and MCL critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors read and approved the fi nal manuscript.

REFERENCES

1 Carter EJ, Pouch SM, Larson EL. The relationship between emergency department crowding and patient outcomes: a systematic review. J Nurs Scholarsh 2014; 46: 106–115.

2 Pines JM, Hilton JA, Weber EJ, Alkemade AJ, Al SH, Anderson PD, et al. International perspectives on emergency department crowding. Acad Emerg Med 2011; 18: 1358–1370.

3 He J, Hou XY, Toloo S, Patrick JR, Fitz GG. Demand for hospital emergency departments: a conceptual understanding. World J Emerg Med 2011; 2: 253–261.

4 Asplin BR, Magid DJ, Rhodes KV, Solberg LI, Lurie N, Camargo CA Jr. A conceptual model of emergency department crowding. Ann Emerg Med 2003; 42: 173–180.

5 Moskop JC, Sklar DP, Geiderman JM, Schears RM, Bookman KJ. Emergency department crowding, part 1—concept, causes, and moral consequences. Ann Emerg Med 2009; 53: 605–611.

6 Chan H, Lo S, Lee L, Lo W, Yu W, Wu Y, et al. Lean techniques for the improvement of patients' fl ow in emergency department. World J Emerg Med 2014; 5: 24–28.

7 Chmiel C, Wang M, Sidler P, Eichler K, Rosemann T, Senn O. Implementation of a hospital-integrated general practice - a successful way to reduce the burden of inappropriate emergencydepartment use. Swiss Med Wkly 2016; 146: w14284.

8 van der Straten LM, van Stel HF, Spee FJ, Vreeburg ME, Schrijvers AJ, Sturms LM. Safety and effi ciency of triaging low urgent self-referred patients to a general practitioner at an acute care post: an observational study. Emerg Med J 2012; 29: 877–881.

9 Thijssen WA, Wijnen-van HM, Koetsenruijter J, Giesen P, Wensing M. The impact on emergency department utilization and patient flows after integrating with a general practitioner cooperative: an observational study. Emerg Med Int 2013; 2013: 364659.

10 Ebrahimi M, Heydari A, Mazlom R, Mirhaghi A. The reliability of the Australasian Triage Scale: a meta-analysis. World J Emerg Med 2015; 6: 94–99.

11 van Gils-van Rooij ES, Yzermans CJ, Broekman SM, Meijboom BR, Welling GP, de Bakker DH. Out-of-hours care collaboration between general practitioners and hospital emergency departments in the Netherlands. J Am Board Fam Med 2015; 28: 807–815.

12 Gaakeer MI, Brand van den CL, Veugelers R, Patka P. Inventory of attendance at Dutch emergency departments and self-referrals (Inventarisatie van SEH-bezoeken en zelfverwijzers). Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd 2014; 158: A7128.

13 van der Linden MC, Lindeboom R, van der Linden N, van den Brand CL, Lam RC, Lucas C, et al. Self-referring patients at the emergency department: appropriateness of ED use and motives for self-referral. Int J Emerg Med 2014; 7: 28.

14 Mackway-Jones K, Marsden J, Windle J. Emergency triage. 2nd Revised edition ed. London: BMJ Publishing Group; 2005.

15 Ramlakhan S, Mason S, O'Keeffe C, Ramtahal A, Ablard S. Primary care services located with EDs: a review of effectiveness. Emerg Med J 2016; Apr 11: [Epub ahead of print].

16 Cooke M, Fisher J, Dale J, McLeod E, Szczepura A, Walley P, et al. Reducing Attendances and Waits in Emergency Departments. A systematic review of present innovations. London: National Coordinating Centre for NHS Service Delivery and Organisation R&D (NCCSDO); 2004.

17 van Gils-van Rooij E, Meijboom B, Broekman S, Yzermans C, de Bakker D. Spoedposten: een verbetering? 2016. Ref Type: Unpublished Work.

Accepted after revision August 29, 2016

10.5847/wjem.j.1920–8642.2016.04.005

Original Article

April 6, 2016

World journal of emergency medicine2016年4期

World journal of emergency medicine2016年4期

- World journal of emergency medicine的其它文章

- Instructions for Authors

- Subject index WJEM 2016

- Author index WJEM 2016

- Stroke due to Bonzai use: two patients

- Emergency department diagnosis of a concealed pleurocutaneous fi stula in a 78-year-old man using point-of-care ultrasound

- When gastroenteritis isn't: a case report of a 20-yearold male with Boerhaave's syndrome complicated by intra-abdomimal hemorrhage