FOUND IN TRANSLATION

TEXT BY NICKY HARMAN PHOTOGRAPHS FROM DOUBAN AND NICKY HARMAN

How well are translated Chinese novels doing?

為什么中國當代文學(xué)作品難以走向國際?

China’s literary scene is lively and prolific,yet it’s largely unfamiliar to English readers.Bookshops in London,where I live,are still shelving Mo Yan’s novels under“Y,” and respected literary critics reviewing Jia Pingwa are on first-name terms,calling him “Pingwa” in their copy.

I have been a literary translator from Chinese for 25 years,but I still puzzle over why so little of China’s contemporary literature gets translated,compared to other languages,and to the amount translated from English to Chinese;and why some Chinese authors go down well with readers,and why some Chinese novels (having been translated) sink without a trace.

Translated fiction from any language has a hard time in English.The depressing figure that used to do the rounds in literary circles was that only 3 percent of literature published in English annually was translated from other languages,colloquially known as the “3 percent problem.” Things are getting better:Neilsen BookData reported that sales of fiction translated from a variety of languages grew by 5.5 percent in the UK in 2018,though few works make it onto bestseller lists.

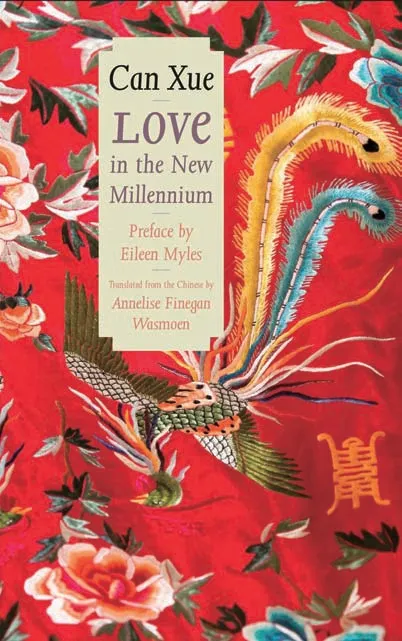

But translations from Chinese lag some way behind,as evidenced by their poor showing in international literary prizes.Since 2019,the number of translations from Chinese that have won international translation awards has been close to zero.In 2019,only one Chinese work appeared on two longlists (the International Booker Prize and the Best Translated Book Award),and got no further—it wasLove in the New Millenniumby Can Xue,translated by Annelise Finegan Wasmoen.

In 2020,no Chinese translations were nominated or shortlisted for major prizes,although 2021 saw some improvement:Strange Beasts of Chinaby Yan Ge and translated by Jeremy Tiang was runner-up in the Warwick Prize for Women in Translation—a significant success.By contrast,Japanese and Korean writers regularly win international prizes.

The Sinophone literary world as a whole (I am including writers from Hong Kong and Taiwan,and Chinese-speaking parts of Southeast Asia) is extremely active and creative,but there is no figure of the international stature and level of recognition of,say,Garcia Marquez,Proust,or Tolstoy.

It is worth looking at a few of the factors that stop great Chinese novels getting into English and into readers’hands.Let’s just say for starters,that the problem is not the lack of translators.There are far more Chinese-English translators now than when I started in the 1990s,and they take translation much more seriously and do it better.

But the cultural background and content of many Chinese novels is very different from what Western readers expect or know anything about.A case in point:Some of the great late-20th century and current writers produce complex,lengthy novels about rural life.If,in addition to their unfamiliarity,these works are poorly translated (yes,it occasionally happens),and published with little to no marketing (that also happens),they are likely to die before they have had a chance to live.

When literature meets diplomacy,the addition of the official touch can be deadening.At the London Book Fair in 2019,a very large Chinese publisher held an event to celebrate the 70th anniversary of the founding of the People’s Republic of China.The books on their shelves included titles such asWalk Your Dream(English edition) andWalk for Peace:Transcultural Experiences in China.I think it’s safe to say that the crowds around those events and stands were sparse.This was in a year when Chen Qiufan and Liu Cixin (science fiction),Jin Yong (wuxia),Jia Pingwa,Wang Anyi,and Li Er (all literary writers) had novels out in English translation—yet none of them were celebrated by big Chinese publishers at the fair.

There are other,more practical,problems.One is lack of access to funding to pay the translator.Translation is a highly-skilled job and a novel takes many months to translate.There is no such thing as an average rate,but it is fair to say that the cost of translation adds thousands to a publisher’s costs.Literary organizations like English PEN and PEN America offer some support for funding translations and the Chinese government also has a limited funding scheme,but most publishers will have to finance themselves.

Another issue,more difficult to quantify,is connected with a lack of mutual understanding and unrealistic expectations.There is little point in Chinese publishers trying to sell to Western publishers a novel which has sold zillions of copies in China,simply on the basis that it’s a bestseller in China.Similarly,it is fairly pointless a Western publisher asking their counterpart for the Chinese Dan Brown or J.K.Rowling.Chinese writing is different,and relegating it to nothing more than the echoes of Western authors is demeaning.For example,there is very little crime writing per se in China,but there are authors,like A Yi,who write excellent novels in which crimes are committed,but which are not easy-read whodunnits or police procedurals.

Can Xue’s Love in the New Millennium (2019)follows a group of women in a dystopian world of informers and permanent surveillance

There have been times when politics was a factor in what got translated.I am cautious about making generalizations,but I think it is fair to say that big Chinese publishing houses are likely to push writers who win prestigious national prizes (like the Mao Dun Prize) when they sell translation rights,and these writers are more often than not male and of an older generation.By contrast,the “banned in China”label has historically been seen by Western publishers as a winner:Ma Jian’s novels have remained consistently popular for their vocal criticism of the Chinese government.All of these factors are lamentable:It means whole swathes of writers never get translated.

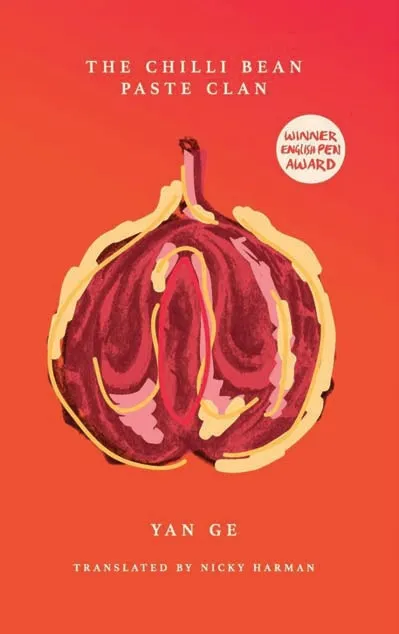

Yan Ge’s The Chilli Bean Paste Clan (2018)was a personal discovery by Harman that won an English PEN Translates award in 2017

So if the gatekeepers of taste are not always reliable,what can we Chinese-to-English translators do about this situation? After all,we all have our favorite authors and favorite works which we desperately want to share with English-language readers.

In my experience,there are two ways for a translator to get their way:They can pitch a book project to publishers and hope to land a contract.When I read Yan Ge’sThe Chilli Bean Paste Clan(2018),a scurrilously cynical story of a drunken,philandering factory boss whose main virtue seems to be his (albeit cowed) loyalty to his tyrannical mother,I loved it enough to prepare a pitch and found Balestier,an indie press brave enough to take on an unknown author.

The author can also come to you.WithChina Along the Yellow Riverby sociologist Cao Jinqing,it was the author’s daughter who persuaded me to take it on.The translation was brought out in very limited numbers by an academic press (Routledge,2006).Since then,I have had several more authors come to me with their books,and help either by doing some of the legwork (Cao Jinqing’s daughter also approached Routledge),putting money towards a sample translation,or both.

Publicizing a new book is an essential part of the process.There’s little point in translating a book if no one is going to read it.The good news is that Chinese authors are usually enthusiastic about pitching in and helping with book promotion.The bad news is that bringing authors to the UK or the US is expensive,prohibitively so for small indie publishers who have led the way in publishing translated fiction.

But if the last couple of years have had an upside,it is to encourage creative workarounds.Some publishers have been very imaginative in running literary events in which they have involved both author and translator.In particular,Sinoist Books run a regular Chinese Literature Reader’s Club and have pioneered ambitious online events combining audiences in China and the West.

Another organization dedicated to raising the profile of translated Chinese fiction is Paper Republic,a registered charity run by translator volunteers.The website includes a database of authors and translators and a selection of free-to-view short fiction designed to interest the general reader.It has gradually gained an international reputation:The London Book Fair International Excellence Awards judges in 2016 called it the“go-to place for Chinese translations and translators.” And then there is the Leeds Centre for New Chinese Writing,based at the University of Leeds in the UK,which runs translation and literature-focused events,workshops,competitions,and book clubs.

Progress,for all of us who translate Chinese literature into English,has been slow—more of a drip-drip than a tsunami.But,looking back over my years of translation,I am greatly encouraged by how many more good translators there are now,compared to when I started out,and by the variety and quality of work they are translating.There’s a huge amount of goodwill generated by working together in organized events and informal support groups.It really is a case of the more the merrier.

Nicky Harman is an award-winning Chinese-English translator based in London.She has taught translation courses at Imperial College London,and was co-Chair of the Translators Association (part of the Society of Authors,UK) from 2014 to 2017.She is a trustee of the non-profit Paper Republic,has been published by Sinoist Books,and collaborates on projects with the Leeds Centre for New Chinese Writing.

THE FRAGRANT COMPANIONS (COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY PRESS,JULY 12)

Early Qing dynasty China was a lenient place.Conservative Neo-Confucianism was out,allowing scandalous iconoclasts like playwright Li Yu to writeThe Fragrant Companionsin 1651.The play was rarely staged over the years,unsurprising when the main plot turns around two beautiful,talented female poets falling in love,marrying (although one already has a scholar-official husband),and eventually living together.Despite an abundance of stories from classical China around homosexual love or extra-marital affairs,tales of female love rarely made it into the public domain.Li took pleasure in tipping the traditional social order upside-down,turning the solemnity of a Confucian marriage into a messy ménage à trois,and the dignity of the imperial exam system into a farcical cavity-search for hidden crib sheets.

THE CONCRETE PLATEAU (CORNELL,JULY 15)

Urban spaces are traditionally viewed as a place of assimilation,where the country bumpkin transforms to smooth city slicker.In the case of multicultural Xining,the provincial capital of Qinghai province inhabited by Muslim,Han,and Tibetan communities,the usual complaint in Western academia is that Tibetan culture is powerless against the irresistible forces of Han-ification.But through an apartment shrine here,or an unofficial Xining origin myth there,Tibetans have created their own cityscape at odds with official plans.Over the course of 17 intermittent months from 2013 to 2017,Professor Andrew Grant of Boston College interviewed a score of Tibetans about their lives and beliefs.Grant’s work is a valuable window into the lived reality of China’s urbanization policies,where not everything at ground level is as neat as the gridded street maps would have you believe.

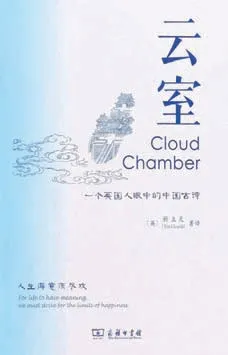

CLOUD CHAMBER (THE COMMERCIAL PRESS,AUGUST 2)

While the floodwaters from a burst river crept up to his doorstep one rainy autumn,seasoned China watcher Tim Clissold found comfort in an unlikely source.Su Dongpo of the Song dynasty (960——1279) lamented the same“exhausting” endless rain which had turned his cottage into “a small fishing boat,” allowing the two men a moment of shared experience that transcended the barriers of time and space.It inspired businessman Clissold,author of the bestselling memoirMr.China,to set about translating a series of classical poems that can resonate with any reader.These lines span two millennia,and can roar to epic heights of a mighty empire undone by one ruler’s lust,then mosey down to the humdrum misery of hair loss.Whatever your mood,it’s certain there’s a Chinese poet who’s been there before.——ALEX COLVILLE